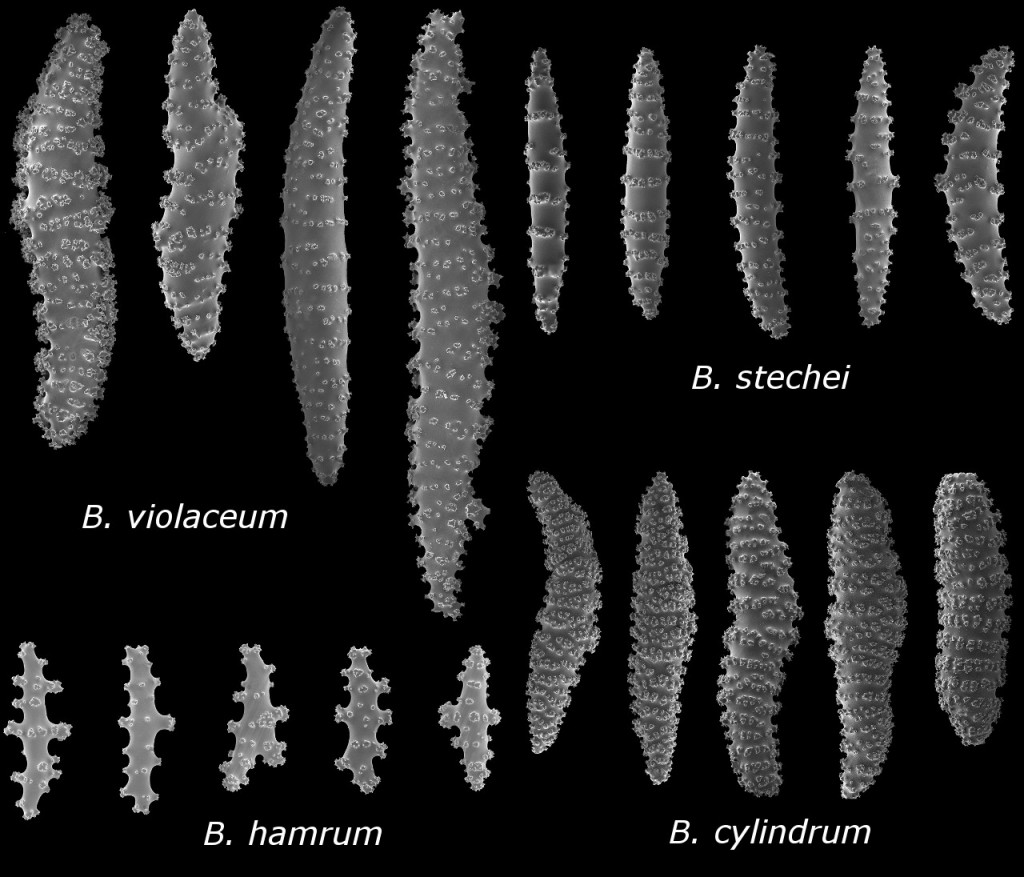

Modified from Samini-Lamin & van Ofwegen, 2016

Green Star Polyps are about as common an aquarium coral as there is, but, if you stare at enough of them, you might notice something unexpected—there are quite a few different varieties of this coral available to aquarists. For instance, some specimens have long tentacles, and some have these much shorter. Some specimens are neon green and others brown. Some have white centers, but many don’t. Some have a knobby texture, while others are mostly flat. Some have feathered edges to their tentacles, and some are entirely smooth. It’s almost as if there are several distinct species of star polyp confused under a single common name. And, unsurprisingly, some newly published research suggests that this is exactly the case.

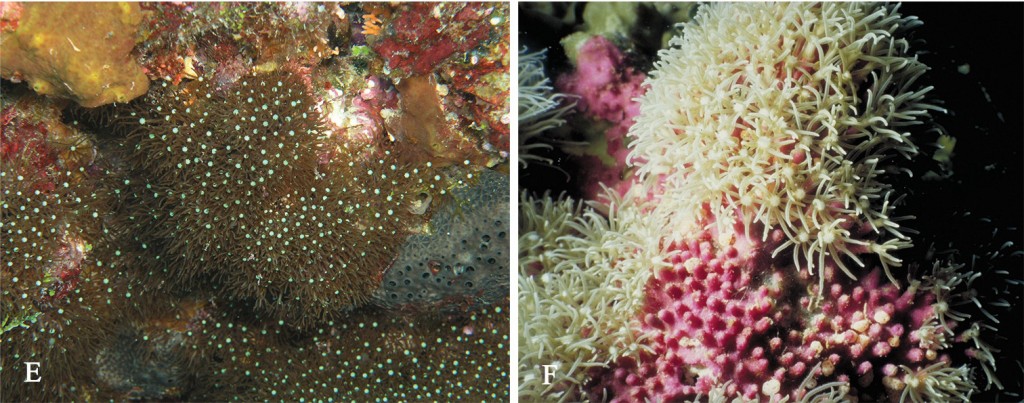

B. violaceum, note the bumpy, purple surface and the contrasting white center to each polyp. It’s uncertain if either of these traits are diagnostic for just this species. Credit: Samini-Lamin & van Ofwegen, 2016

If you’ve spent any time pondering soft coral taxonomy, you’ll be struck by the fact that we know remarkably little when it comes to the basics of what constitutes a species, particularly so for the more diverse genera. Taxonomists have traditionally relied on the minute calcareous sclerites of these corals for establishing the limits for where one species stops and another starts, but these have oftentimes proven to correlate poorly with genetic study. Of course, relying solely on microscopic internal structures for making an identification doesn’t lend itself well to the average aquarist looking to ID their specimen… which brings me back to the uncertainty surrounding star polyps.

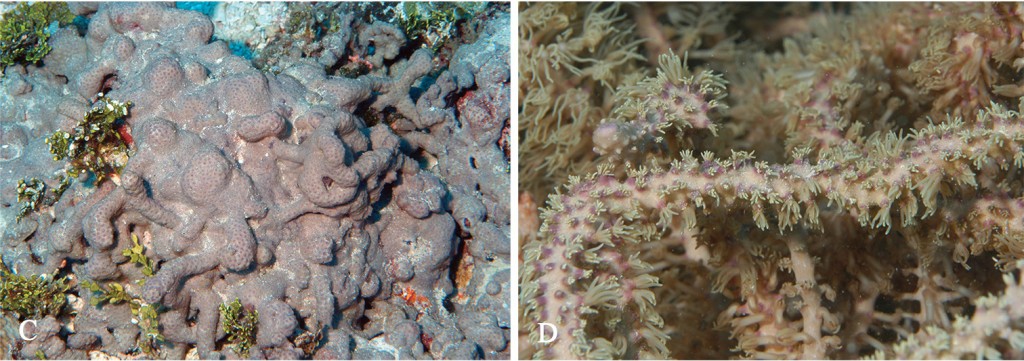

B. hamrum is a species thought to be restricted to the African and Arabian coatlines, but which bears a striking similarity to specimens observed in Singapore, as well as some rarer aquarium specimens. Credit: Samini-Lamin & van Ofwegen, 2016

In a morphological and genetic study of Japanese specimens (Miyazaki & Reimer, 2014), three distinct varieties—presumed to be separate, but unidentified, species—were recognized. The key characteristics for recognizing these “species” relate to the shape of the surface sclerites, the color of the colony, the relative protrusion of the polyps above the colony’s surface, and the manner in which the tentacles are held open. Unfortunately, the genetic data for these is all but equivocal, calling into question just how distinct these three truly are. There are undoubtedly multiple species present, as, when seen growing side by side, these corals do look different from each other, but little else can be said concerning specific details of this.

The smooth, pale surface and contorted shape of this P. stechei colony is similar to many aquarium specimens. Credit: Samini-Lamin & van Ofwegen, 2016

A recent morphological revision of Briareum (Samini-Lamin & van Ofwegen, 2016) found a similar number of species in the Pacific. Again, the main diagnostic criteria relates to the shape of the sclerites found along the surface (=cortical) between the polyps, as well as their coloration. The most familiar name here (Briareum violaceum) corresponds to a species with particularly enlarged (up to 1mm) and pointed sclerites that are purple in coloration throughout the body. Based on the specimens examined, the colonies appear darkly purple on the surface, with prominently raised polyps, though it remains unknown how consistent this is as an identifying trait. It’s likely that this is the most abundant species available in the aquarium trade, though this requires confirmation. Also, note that many older aquarium sources will recognize this coral under the synonymized name Pachyclavularia violacea.

An unusual solid green specimen with small tentacles. A species identification on this is essentially impossible without scleritic study. Credit: Remix

The newly described B. cylindrum has markedly different sclerites, which measure on average only 0.3mm and have a blunter shape with more complex and densely arranged tubercles. The surface of the holotype specimen is pale, and the cortical sclerites are clear rather than purple. The polyps are mostly embedded within the coenenchymal tissue, giving this species a markedly smoother appearance. This matches quite well with the Type-2 Briareum of Miyazaki & Reimer, as well as a variation of star polyps common to the aquarium industry which is often exported as loose, unattached pieces with a rather haggard and uneven look. Put bluntly, this is a fairly unattractive species which most aquarists would pass over for B. violaceum, though it’s important to note that there are no positively identified live specimens of this yet, so this identification is only tentative.

A specimen from an intertidal habitat in Singapore, somewhat similar to B. hamrum. Credit: budak

The last of the Pacific species is P. stechei, which likewise appears to have a pale and smooth surface. Unlike the previous species, this coral has relatively large cortical sclerites measuring up to 0.75mm, which are clear in color (compared to the similarly sized but purple sclerites of B. violaceum). It’s likely this species is being exported for the aquarium industry, as specimens superficially matching this description abound, but, without more information on what stechei and cylindrum look like in life, it’s impossible to say more on the subject.

An aquarium specimen similar to the above. Note the unusual color of the tentacles and oral disc, as well as the unusually feathery (pinnate) morphology. Credit: empatikiyatik

Two more species warrant brief mention. B. hamrum is an interesting coral reported only from the coasts of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Its sclerites are small, measuring only to 0.35mm, and the colonies are said to be mostly cream or brown in color, with white lines radiating down the tentacles. A somewhat similar phenotype has been photographed from the intertidal reefs of Singapore, though whether it bears any relation to this species or one of the preceding Pacific taxa is unknown. In all likelihood, B. hamrum is a geographically restricted species which is unavailable to the aquarium industry.

This specimen is almost certainly either B. stechei or B. cylindrum. Note the smooth, contorted shape to the coenenchyme, as well as the concolorous oral disc. Credit: Sushi Girl

A single Atlantic star polyp exists in the form of B. asbestinum, commonly known as the Corky Sea Finger. This species is notable for forming erect, branched colonies that take on the appearance of a thick gorgonian. Typically brown in color, this coral is a regularly available, though decidedly underappreciated, species in the aquarium hobby.

The purple color, tall polyps (anthostelae), large white oral discs and small tentacles seem to match well with depictions of B. violaceum from the literature. Credit: Tahirah Shadforth

As the photos in this article should make clear, there is a wide variety in the shape of Briareum polyps. Some of this is likely due to the conditions in which these corals grew in the wild (light intensity, water velocity, sedimentation, etc), while some is representative of species level differences. The difficulty faced by both zoologists and aquarists alike is determining which is which… how do we recognize where one species starts and another stops without dissolving their tissue and grabbing a microscope? There is a great need for more research into this group, particularly as it relates to the appearance of live specimens (the shape and coloration of the polyps and so on). For the time being, it remains essentially impossible to definitively identify aquarium star polyps from external features alone.

An unusual brown specimen, which is likely Briareum. Acrossota amboinensis is a superficially similar coral which lacks feathery edges (pinnae) to the tentacles and grows via a thin strip of tissue (stolon) rather than a thick mat. Credit: JenLen.ru

Another attractive green specimen of unknown species identification. Note the B. violaceum-like color and morphology to the coenenchyme and anthostelae, but the lack of a white orla disc calls this into question. Credit: aquaism

Another unusual specimen, with pale, smooth coenenchyme, somewhat similar to the Singaporean B. cf hamrum shown above. Credit: DeJong Marinelife

The large white oral discs intimate at B. violaceum, but note how this specimen entirely lacks pinnae on the tentacles. This feature seems to vary wildly between specimens. Credit: Joe Kwok

0 Comments