One of the most exciting things about my job is watching larval fish develop when I have no idea what species they are. I spend hours peering into my larval rearing tanks, looking for similarities between the larvae and the fishes in our 20,000-gallon coral reef tank, from which we regularly collect pelagic eggs.

Ideally, I would be able to raise each species to the point of its final metamorphosis which would make identification very easy, however since most of the species in that tank have never been raised in captivity, virtually nothing is known about their larval requirements. Needless to say, although I have many opportunities to try my hand at raising a variety of difficult marine species, I am often denied the satisfaction of finding out which species are swimming around in my rearing tanks. It can be very frustrating at times, especially when I watch larvae eating and growing for a month or more, but then I lose them before settlement (as in the case of the Genicanthus angels), but it’s all part of the mixed blessing of trying to conduct aquaculture research at a public aquarium. The time, space, and energy I devote to raising fish larvae are often at odds with my responsibilities as an aquarist. First and foremost, I need to keep my exhibits and their inhabitants in perfect condition. Then I need to maintain all my cultures of phytoplankton, rotifers, and copepods. Then there’s the broodstock system with clowns, gobies, basslets, and other assorted fishes. I know I could make my life easier and achieve greater success by collecting wild plankton and spending less of my days culturing live foods, but I continue to resist the temptation as my ultimate goal is to develop sustainable and reproducible techniques for culturing as many species as possible.

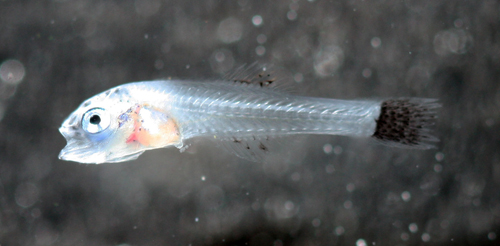

Last year an interesting larva began to show up in samples that hatched from pelagic eggs collected from our reef tank. They were very tiny, and had a nutritional reserve in the form of an oil droplet that lasted about three days, at which time they needed to start feeding (this is very common in pelagic spawners). At first feeding they appeared to be too small to ingest rotifers, but they readily accepted nauplii of Parvocalanus crassirotris, one of three copepod species that I keep in culture here, that were originally obtained from Algagen. On several occasions these larvae made it to around one month of age and reached some encouraging developmental milestones like flexion and proliferation of pigment cells before succumbing to…whatever it is that tends to kill off larvae in culture tanks: nutritional deficiencies, deteriorating water quality, bacterial blooms. However, with the persistence of a person who won’t allow himself to buy his next bottle of Bombay Sapphire until a new species has been raised successfully, I have chipped away at this problem over the past year and have finally gotten a handful of them through metamorphosis.

And now, the moment you’ve all been waiting for: The species is….

The barred flagtail, Kuhlia mugil.

I know, it’s no candy bass or angelfish. In fact its coloration is so unremarkable, it could pass for a freshwater fish, but between the high mortality and a larval period of nearly three months, it was as difficult as any species I’ve tackled so far. They were fed a diet of copepods (Parvocalanus, Acartia, and Pseudodiaptomus) and rotifers throughout the larval period and have now been weaned onto Cyclo-eeze and Artemia.

I should point out that what the barred flagtail lacks in brilliant coloration, it makes up for in the visual contrast it brings to reefs with its silvery scales and tight schooling behavior. I’m told they’re pretty good to eat as well.

For more a more in-depth discussion on the rearing techniques for this and other species, check out the Bucks County Aquarium Society’s annual workshop on Saturday June 8 and the New Jersey Reefers Frag Swap and conference on June 15.

0 Comments