Until now, there wasn’t much fact concerning exactly how reef fish larvae can travel away from their home reef and still find their way back again. In a recent study conducted by Dr. Claire Paris, Professor at the University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science, data regarding the use of smell in larvae at One Tree Island in the Great Barrier Reef was collected. This study presents new material which would suggest that a reef’s scent trail can be picked up and used for navigation from miles away.

Until now, there wasn’t much fact concerning exactly how reef fish larvae can travel away from their home reef and still find their way back again. In a recent study conducted by Dr. Claire Paris, Professor at the University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science, data regarding the use of smell in larvae at One Tree Island in the Great Barrier Reef was collected. This study presents new material which would suggest that a reef’s scent trail can be picked up and used for navigation from miles away.

Experiments in controlled conditions have already proven that fish larvae can distinguish between different reefs simply by smell, however, it was hard to predict how this would translate to real world conditions.

“In this collaborative study we expanded our work to demonstrate that the odor responses can also be detected under the field conditions,” said Dr. Jelle Atema, Boston University Professor of Biology. “This establishes for the first time that reef fish larvae discriminate odor in situ.”

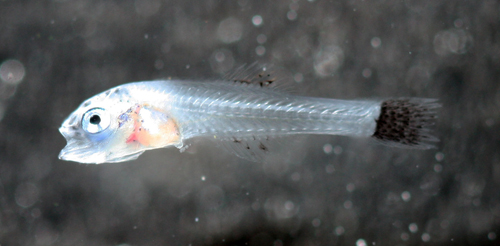

The most recent study was designed to test these abilities in the open ocean with an outflow plume from One Tree Island being the testing grounds and with the subjects being cardinal and damsel larvae collected in the same area.

For the experiment a unique device, called an o-DISC (ocean Drifting In Situ Chamber,) which is designed to be transparent to light, sound and small flow patterns was used to monitor the larvae’s activity. This was coupled with motion tracking instruments in order to see exactly how the fish responded.

Recorder reactions were very different between the two species tested with the cardinal appearing to use sporadic odor cues to home in on their home reef in zig-zag patterns while the damsels appeared to slow down, lock on and navigate as if using a compass.

“Ocean currents do not appear to influence the orientation of fish larvae,” said Paris. “They do not provide a frame of reference since larvae are transported within. Instead, we find that fish larvae navigate by detecting turbulent odor signals transported kilometers away from the reef. Subsequently they switch to a directional cue, perhaps magnetic or acoustic, which allows them to find the reef.”

It’s been found in the past that sharks as well as some other fish use scent for navigation, but this is the first time the theory has been put to the test with reef fish larvae.

“The implications of this study are tremendous, because we have to take into account the impact that human activities might have on the smells contained within the ocean. If these larvae cannot get their ‘wake up’ cues to orient back toward the reef they may stay out at sea and become easy prey before finding home,” said Paris.

0 Comments