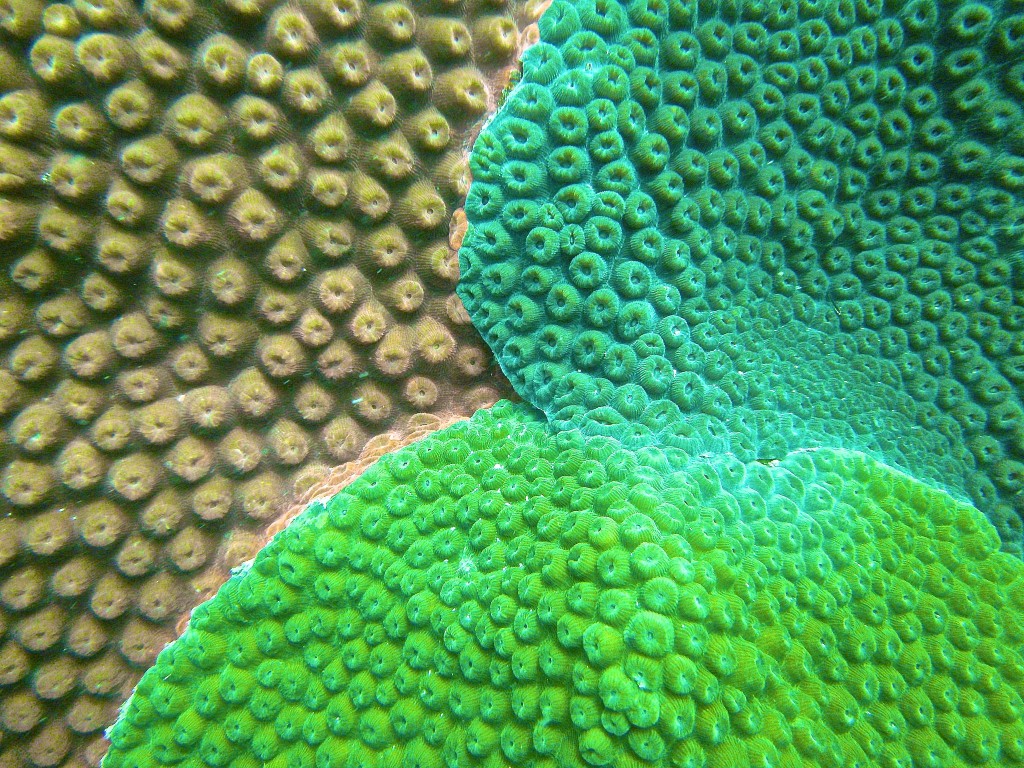

Merulinidae: Astrea

Four extant species (and two extinct) species make up this newly recognized genus. The species are mostly former Montastraea (plus one Plesiastrea) that are identifiable by their symmetrically-round polyps and intracalicular growth. It should come as no surprise that they are similar to the Indo-Pacific “Montastraea” (now placed in Favites) but differ in having smaller polyps (~5mm vs ~10mm) that are mostly round (vs irregularly oval).

A. rotulosa is known only from the holotype specimen (which lacks a collection locality), and it is nearly identical to the West Indian Ocean endemic A. devantieri. Dr. Danwei Huang (pers. comm.) has intimated that they are quite likely synonymous, but it may be a while before this is sorted out.

Astrea curta and annuligera are far more common and well-documented species. In particular, curta is reported as being one of the more common merulinids on reefs, and it does occasionally find itself collected for aquariums, often in the traditional colors of the “X-mas favia”. These two species of Astrea are easy to tell apart, as annuligera has highly exsert septa.

[Astrea is unfortunately very similar in spelling to the common aquarium snail Astraea (note the extra ‘a’). The correct pronunciation for the coral is “AH-stray-uh” and for the snail is “AH-stree-uh”. I agree that it is quite confusing.]

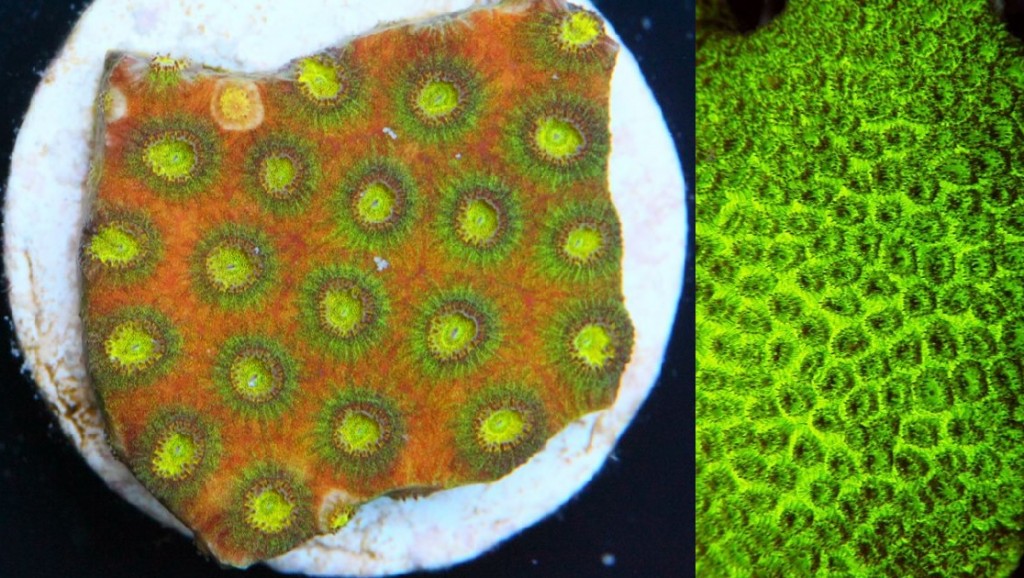

Merulinidae: Cyphastrea

The eight species of Cyphastrea are easily identifiable by their small (< 3mm) plocoid polyps, extracalicular budding and spinose coenosteum. The only merulinid that bears any close resemblance is the Atlantic Orbicella, but aquarists are far more likely to confuse Cyphastrea with a similarly small-polyped coral like Astreopora or Pavona maldivensis. While the genus is easy enough to recognize, the species are quite challenging to identify, requiring a close examination of the septa.

The most common and widespread species is C. serialia, which has 12 septa in two cycles. A similar species, also common, is chalcidium, which differs in having costa that alternate in size (this is somewhat visible through the tissue). C. micropthalma, another common species, differs in having septa in cycles of 10. C. japonica, ocellina and agassizi are less common species that will pose a challenge to identify. Colonies of Cyphastrea seen for sale are typically rather small, and the polyps can vary in how closely spaced they are. Coloration ranges from bright green to orange to the highly sought after teal with orange polyps variety called “meteor shower”.

The most distinct species is the branching C. decadia, which forms small, bushy colonies. The axial corallite found on the tip of each branch is a feature shared only with Acropora. While reported as rare in the wild, colonies have appeared amongst aquarists, often as cultured frags. Coloration consists of orange polyps with either orange or blueish coenosarc.

Merulinidae: Orbicella

The Atlantic endemic Orbicella has traditionally been treated under the name Montastraea, but molecular and morphological evidence strongly support its position amongst the rest of the Indo-Pacific Merulinidae. The three species of Orbicella form a well-documented species group that has received extensive study (molecular, morphological, ecological, and reproductive) which has resolved the longstanding confusion within the group.

Orbicella is recognizable from the shape of its small polyps and spinose coenosteum. The closest comparison in the Atlantic is Montastraea cavernosa, which has far larger polyps. Genetically, its sister group is Cyphastrea, which similarly has small polyps and a spinose coenosteum.

Montastraeidae: Montastraea

Only a single coral—the Atlantic endemic M. cavernosa—comprises this formerly speciose group. The genus (in its former, broader sense) was united primarily by the presence of extracalicular budding, but genetic evidence has shown this concept to be laughably wrong, with there being perhaps six unrelated groups lumped together. The former members are now spread amongst Astrea, Paramontastraea, Orbicella, Favites, as well as “M. multipunctata”, which belongs to the separate family Lobophylliidae (and will eventually be moved to Micromussa!). If you ever feel overwhelmed by the difficulties of coral identification, know that you are in good company.

Montastraea cavernosa is a distinctive species, now placed in its own family, which is most likely sister to all the mussids, lobophylliids, and merulinids. It is readily identifiable from its medium to large (4-15mm) polyps that protrude strongly from the surface of the coenosteum. The septa are particularly numerous and closely-spaced, and the columellae are relatively large compared to the calice diameter. Coloration varies from green to brown to occasionally red.

Diploastraidae: Diploastrea

A single distinctive species comprises this genus. While traditionally treated under the old family Faviidae, molecular study has shown it to be quite distantly related, forming a sister group to Montastraeidae+Mussidae+Lobophylliidae+Merulinidae. This is not a terribly surprising revelation given the fossil record of this group, which stretches all the way back to the Lower Cretaceous. If Jurassic Park had a reef tank, Diploastrea would be in it.

There are numerous micromorphological and microstructural differences that show this coral to be unique, one of which is the synapticulothecate structure of the thecal walls, which is more often seen in distantly related corals with lightweight skeletons like Porites and Acropora. The shape of the septal teeth is also unique, being pointy with an elliptical base parallel to the septa. Living colonies are easily recognized by the hillocky, trapezoidal polyps with unusually small oral disks. The costae radiate outwards from these small oral disks like the rays from a tiny sun (heliopora is from the Ancient Greek for “sun-shaped pore”). Coloration varies from brown to green. The majority of specimens seen for sale are maricultured in Bali.

Plesiastreidae: Plesiastrea

While this group has often been aligned with the superficially similar Faviidae in older classifications, molecular data indicates it occupies its own clade in the coral tree of life, Its closest known relatives are two deepwater, azooxanthellate species that seem to bear no obvious similarities to it (one is solitary, the other branched). What they do seem to share is the presence of pali—structures which appear similar to paliform lobes but are ultimately created in a fundamentally different manner.

P. versapora, the only currently recognized species, was originally described in Astrea, later being moved to Favia and Orbicella before landing in its current nomenclatural home. Many other superficially similar and equally odd species (G. stelligera, A. devantieri, P. salebrosa) have come and gone from this genus, but it’s clear now that versipora belongs to its own unique branch of coral evolution.

Specimens are fairly easy to identify. Polyps are small (~2.5mm), extracalicularly budded and vary from strongly plocoid to subcerioid, with varying amounts of calice relief. The columella is unusually small and composed of just a few papillae (versus the spongy mass of most merulinids), and the septa extend deep within the calice, with a prominent crown of pali (vs paliform lobes) present. The coenosteum varies from smooth to costate.

The only coral this species might be confused with is possibly Cyphastraea, which differs in several of the characters listed and generally has more exsert polyps. This species is quite uncommon in the aquarium hobby, but it does pop up sporadically, often as small fragged colonies. Specimens can come in a rainbow of colors, and this species would strongly benefit from increased propagation. Its combination of colony shape and coloration make it stand out, and, coupled with its unique evolutionary story, this is a coral any reefer should desire for their aquarium.

Incertae sedis: Solenastrea

Incertae sedis (Latin, meaning “of uncertain placement”) refers to the lack on an established name for this family level group. Two species restricted to the Atlantic Ocean comprise this small, well-defined genus. While traditionally treated as being closely related to “Montastraea”, molecular research identifies Solenastrea as being far removed from all the previously discussed corals. Its closest relatives are obscure genera like Cladocora (also a former faviid) and Oculina, as well as the Atlantic Meandrinidae. It may well end up in its own family, Solenastreidae, or maybe join its closest relatives in a possible Cladocoridae.

These species do bear a general resemblance to Orbicella (formerly placed in Montastraea). Solenastrea differs in having a smooth (vs spinose) coenosteum. An even more important difference is the compact shape of the columellae compared to the large spongy columellae of Orbicella. Solenastrea forms irregularly shaped, columnar colonies. Polyps are small and flush with the surface, and the coloration is cream or brown. Polyps have relatively long tentacles that are often extended during the day.

Incertae sedis: Leptastraea

Another genus traditionally grouped under the former family Faviidae, the seven recognized species of Leptastrea are now known to be another distant relation. They share a deep branch with seemingly dissimilar corals like Psammocora and Fungia, which is sister to the heterogeneous group of corals we’ve examined thus far.

Leptastrea possess small (~3mm, sometimes to 11mm) polyps that bud extracalicularly. Polyps vary amongst the species from cerioid to plocoid. The coenosteum is generally lacking in any sculpuration, and, distinctively, the columella is composed of several tiny, spine-like projections (vs the spongy columellae of merulinds). An interesting habit is the ability to form small, free-living colonies called coralliths, which roll about the ocean floor with the movement of the waves. Such colonies can reach up to 15cm across, and are known from a variety of unrelated groups. Cyphastraea is another example, specimens of which occasionally are collected for aquarists. Inevitably, the bottom of such colonies will die off in captivity without constant shifting of the colony.

The most common species on reefs is L. purpurea, which possesses variably colored oral disks on a solidly-white or marbled background. The polyps are strongly cerioid and polygonal, a trait shared with the nearly identical L. transversa. These two species form irregularly-shaped massive or encrusting colonies, with polyps residing in surface concavities being smaller (~2mm) than those in the convexities (up to 11mm). A third species shares these basic similarities but can be told apart by its habit of extending its tentacles during the day. This species, L. pruinosa, is the species most commonly encountered by aquarists. There are a bewildering variety of colors seen, from purples to orange to aqua to green to red.

The remaining species differ dramatically from the previous taxa in being mostly plocoid, with round, symmetrical calices that are rather homogeneously-sized, and with fewer septa that reach less-deeply into the calice and project more-exsertedly above. As can be seen, these species are fundamentally different, and it isn’t clear if this is truly a monophyletic group. Only a single species, L. pruinosa, has been studied genetically, and none of the members has undergone a thorough morphological analysis. Many questions remain unanswered.

Insertae sedis: Oulastrea

A single species, O. cripata, comprises this genus. The classification has varied, with the early work of Vaughan & Wells aligning it near Agaricia and Veron’s work uniting it with the macromorphologically similar “Faviidae”. Molecular evidence now indicates both were wrong, and this group resides on the same deep branch as Leptastrea. Little work has been published to indicate what these disparate groups might share as morphological characters.

Oulastrea crispata is an extraordinary species, being the most-Northerly occurring shallow water reef-building coral in the world. Specimens from Japan and the Mediterranean regularly experience near-freezing temperatures. A unique adaptation which may help it survive in these extreme environments is the presence of dark pigments within its skeleton. The amount is known to vary widely between locations, and it’s not understood what role this coloration plays. Pigmented skeletons are exceedingly rare in stony corals, and helps to instantly diagnose this species. There is little coloration to the tissue, so this black pigment shows through. The exsert septa are not pigmented, and thus provide an attractively contrasted white, which gives the coral its common name of “zebra coral”.

Ecologically, this species is almost exclusively found along rocky shorelines and shallow reef flats, often as the only species present. In more diverse habitats it is almost non-existent, which may be an indication of its inability to compete. In the right habitat it is reported to be somewhat common, but it is a species that has to be sought out to find it. Because of this, and the lack of demand for less colorful corals, this fascinating species is unavailable to aquarists. While it may not be everyone’s cup of tea, this would undoubtedly make for the perfect beginner’s coral.

Other Brain-like Taxa

A few other groups have evolved a similarly brain-like composition. These species are almost entirely unknown from the aquarium trade, with the exception of the occasional Gardineroseris that has been reported. It’s unfortunate that these unusual corals aren’t sought after enough to warrant collection. Keep an eye out for these species as hitchhikers on larger coral pieces.

While these species have hit upon the same look of many “brain corals”, they belong to a far distant branch on the coral tree of life, being more closely related to groups like Acropora and Porites, which have skeletons of a far more diaphanous nature. While it may not be apparent, the structure of the skeleton is fundamentally different from the more “robust” groups like merulinids, lobophylliids, and mussids.

Pseudosiderastrea has one widespread species and a second known from Southeast Asia. The polygonal polyps that sit flush in the coenosteum are characteristic. The coloration varies from green to brown, usually with white thecae. While I’ve never seen this species purposefully exported, I have seen small colonies growing inconspicuously alongside pieces of more “desirable” coral. Siderastrea is a close relative, known mostly from the Atlantic, with a single species known from the Indo-Pacific. The two groups constitute the family Siderastreidae, which is sister to all the groups we’ve already covered.

Gardineroseris planulata is the only species in its genus, and it is placed alongside more familiar corals like Pavona and Leptoseris in the Agariciidae. It bears some resemblance to Pseudosiderastrea, but the coloration is mostly brown, the septa are finer and more numerous, and colonies reach a much larger size. The angular, polygonal walls and scooped out corallites give this coral a handsome and unmistakable look. Another species for the coral connoisseur.

Acknowledgements

A special thank you to Dr. Danwei Huang for generously reviewing this article.

References

Arrigoni, R., Stefani, F., Pichon, M., Galli, & P., Benzoni, F. 2012. Molecular phylogeny of the Robust clade (Faviidae, Mussidae, Merulinidae, and Pectiniidae): an Indian Ocean perspective. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 65: 183-193.

Arrigoni, R., Terraneo, T. I., Galli, P., & Benzoni, F. 2014. Lobophylliidae (Cnidaria, Scleractinia) reshuffled: pervasive non-monophyly at genus level. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 73: 60-64.

Benzoni, F., Arrigoni, R., Stefani, F., & Pichon, M. 2011 Phylogeny of the coral genus Plesiaastrea (Cnidaria, Scleractinia). Contributions to Zoology 80: 231-249.

Blainville, H. M. de 1830. Zoophytes. In: Dictionnaire des sciences naturelles, dans lequel on traitre méthodiquement des differéns êtres de la nature, considérés soit en eux-mêmes, d’après l’état actuel de nos connoissances, soit relativement a l’utlité qu’en peuvent retirer la médicine, l’agriculture, le commerce et les arts. Edited by F. G. Levrault. Tome 60. Paris, Le Normat. Pp. 548, pls. 68.

Borneman, E. 2001. Aquarium Corals: Selection, Husbandry, and Natural History. Charlotte, VT: Microcosm.

Budd, A. F., Fukami, H., Smith, N. D., & Knowlton, N. 2012. Taxonomic classification of the reef coral family Mussidae (CnidariaL Anthozoa: Scleractinia) Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 166: 465-529.

Budd, A. F., & Stolarksi, J. 2009. Searching for new morphological characters in the systematics of scleractinian reef corals: comparison of septal teeth and granules between Atlantic and Pacific Mussidae. Acta Zoologica 90: 142-165

Budd, A. F., & Stolarski, J. 2011. Corallite wall and septal microstructure in scleractinian reef corals: comparison of molecular clades within the family Faviidae. Journal of Morphology 272: 66-88.

Dai, C. F., & Horng, S. 2009. Scleractinia Fauna of Taiwan II. The Robust Group. Taiwan: National Taiwan University.

Fukami, H., Budd, A. F., Paulay, G., Sole-Cava, A. M., Chen, C. A., Iwao, K., & Knowlton, N. 2004. Conventional taxonomy obscures deep divergence between Pacific and Atlantic corals. Nature 427: 832-835.

Fukami, H., Chen, C. A., Budd, A. F., Collins, A. G., Wallace, C. C., Chuang, Y. Y., Dai, C. F., Iwao, K., Sheppard, C. R. C., & Knowlton, N. 2008. Mitochondrial and nuclear genes suggest that stony corals are monophyletic but most families of stony corals are not (Order Scleractinia, Class Anthozoa, Phylum Cnidaria). PLoS ONE 3: e3222

Huang, D., Benzoni, F., Fukami, H., Knowlton, N., Smith, N. D., & Budd, A. F. 2014a. Taxonomic classification of the reef coral families Merulinidae, Montastraeidae and Diploastraeidae (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Scleractinia). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 171: 277-355.

Huang, D., Benzoni, F., Arrigoni, R., Baird, A. H., Berumen, M. L., Bouwmeester, J., Chour, L. M., Fukami, H., Licuanan, W., Lovell, E. R., Meier, R., Todd, P. A., & Budd, A. F. 2014b. Toward a phylogenetic classification of reef corals: the Indo-Pacific genera Merulina, Goniastrea and Scapophyllia (Scleractinia, Merulinidae). Zoologica Scripta 43: 531-548.

Huang, D., Licuanan, W. Y., Baird, A. H., & Fukami, H. 2011. Cleaning up the “Bigmessidae”: molecular phylogeny of scleractinian corals from Faviidae, Merulinidae, Pectiniidae and Trachyphylliidae. BMC Evolutionary Biology 11: 37.

Huang, D., Meier, R., Todd, P. A., & Chou, L. M. 2009. More evidence for pervasive paraphyly in scleractinian corals: systematic study of Southeast Asian Faviidae (Cnidaria: Scleractinia) based on molecular and morphological data. Moelcular Phylogenetics and Evolution 50: 102-116.

Matthai, G. 1914. A revision of the Recent colonial Astræidæ possessing distinct corallites. Transactions of the Linnean Society of London 17: 1–140.

Moll, H., Best, M. B. 1984. New scleractinian corals (Anthozoa: Scleractinia) from the Spermonde Archipelago, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Zoologische Mededelingen Leiden 58: 47–58.

Sprung, J. 1999. Corals: A Quick Reference Guide. Coconut Grove, FL: Ricordea Pub.

Vaughan, T. W., & Wells, J. W. 1943. Revision of the suborders, families, and genera of the Scleractinia. Geological Society of America Special Papers 44: 1-345 (pl. 1-51).

Veron, J. E. N. 1990. New Scleractinia from Australian coral reefs. Records of the Western Australian Museum 12: 147-183.

Veron, J. E. N. 2000. Corals of the World. Townsville Australian Institute of Marine Science.

Veron, J. E. N. 2002. New species described in Corals of the world. Townsville: Australian Institute of Marine Science.

Veron, J. 2013. Overview of the Taxonomy of Zooxanthellate Scleractinia. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 169.3: 485-508.

Veron, J. E. N., Pinchon, M., Wijsman-Best, M. 1977. Scleractinia of Eastern Australia. Part II. Families Faviidae, Trachyphylliidae. Townsville: Australian Institute of Marine Science.

Verrill, A. E. 1901. Variations and nomenclature of Bermudian, West Indian, and Brazilian reef corals, with notes on various Indo-Pacific corals. Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences 11: 63–168, pl. 10–35.

Wijsman-Best, M. 1972. Systematics and ecology of the New Caledonian Faviinae (Coelenterate – Scleractinia). Contributions to Zoology 42:3-90

Wijsman-Best, M. 1974 Biological results of the Snellian Expedition. XXV. Faviidae collected by the Snellius Expedition. I. The genus Favia. Zoologische Mededelingen Leiden 48: 249-261.

Wijsman-Best, M. 1976 Biological results of the Snellian Expedition. XXVII. Faviidae collected by the Snellius Expedition. II The Genera Favites, Goniastrea, Platygyra, Oulophyllia, Leptoria, Hydnophora and Caulastrea. Zoologische Mededelingen Leiden 50: 45-63.

Wijsman-Best, M. 1977 Indo-Pacific coral species belonging to the subfamily Montastreinae Vaughan & Wells, 1943 (Scleractinia-Coelenterata) Part I. The genera Montastrea and Plesiastrea. Zoologische Mededelingen Leiden 52: 81-97.

Wijsman-Best, M. 1980 Indo-Pacific coral species belonging to the subfamily Montastreinae Vaughan & Wells, 1943 (Scleractinia-Coelenterata) Part II. The genera Cyphastrea, Leptastrea, Echinopora and Diploastrea. Zoologische Mededelingen Leiden 52: 81-97.

Yamashiro, H. 2000. Variation and plasticity of skeleton color in the zebra coral Oulastrea crispata. Zoological Science 17(6): 827-831.

0 Comments