The genus Terelabrus was first erected in 1998 based on an unknown labrid collected at 100m in Bulari Pass, New Caledonia. The species was described as T. rubrovittatus, and since then, has managed to remain the sole representative for the genus. Through the passing of time, in accordance to the development and growth of the ornamental fish industry, two new phenotypes have since been discovered – one from the Western Pacific and the Western Indian Ocean respectively. Although these potentially distinct phenotypes have been widely known for years, no formal taxonomic treatment has been given, and as such, have greatly exacerbated in fueling the ongoing erroneous labeling of the species. In the latest paper published by Fukui and Motomura, the Western Pacific phenotype has been recognized and elevated to full species level. T. dewapyle now relinquishes T. rubrovittatus from being the sole representative of the previously monotypic genus Terelabrus.

T. rubrovittatus. Notice the white stripe between the two equatorial red stripes. Photo credit: H. Senou.

Terelabrus rubrovittatus was first known from a male, measuring 87mm, collected at 100m in New Caledonia, 1979. However, the description paper was held off until a second specimen could be collected and examined. It was only 16 years later in 1995 that a juvenile specimen was collected at 92m in Milne Bay. This was thought* to be the same species, and with the new paratype, the species was described officially in 1998. The distinctively different body profile and meristics compared to other labrids warranted an erection of a new genus and species. The generic epithet Terelabrus is an amalgamation of the latin words teres, meaning terete, and labrus, for wrasse, owing to the narrow cylindrical (terete) shape of the fish. The specific epithet rubrovittatus is a literal translation for “red stripe”. T. rubrovittatus served as the type species for the genus. Because of the species’ proclivity for deep water, T. rubrovittatus is very poorly known in museums and the aquarium trade.

A smaller, more diminutive phenotype from the Western Pacific has emerged with some regularity in the last decade. This recalls that of T. rubrovittatus, but is significantly more slender, and colored differently. It also occurs in generally shallower waters, up to 20m, which would explain its greater prominence in literature and the ornamental trade. Unfortunately, because the type species representing this genus was so poorly known, this phenotype has been erroneously identified as the latter for an extended period of time – so much so that it has now been deeply ingrained in books, articles and other literary resources. *It has since been revealed, during the description of the new species, that the paratype for T. rubrovittatus collected in Milne Bay was actually synonymous with the undescribed Western Pacific phenotype, going to show that even in scientific documentations, this confusion is rife and not uncommon. As such, T. rubrovittatus is known only from a single holotype from Bulari Pass (the paratype is herein identified as T. dewapyle).

T. rubrovittatus in situ. Note the superimposed vertical blotches, and the white stripe between the two red stripes. Photo credit: M. Watanabe.

The latest paper by Yoshino Fukui and Hiroyuki Motomura published in Zootaxa has since addressed this conundrum, awarding the name T. dewapyle to the Western Pacific phenotype. It was described from a holotype collected off the coast of Iou-jima, Kagoshima, Japan, at a depth of 72m, and four holotypes, one of which was the sole paratype of T. rubrovittatus that was wrongly identified. It is distinguished from T. rubrovittatus in meristics and coloration. In T. rubrovittatus, the equatorial red midlateral stripe is superimposed with a series of vertical blotches, which is absent in T. dewapyle. Instead, the latter possesses a horizontal yellow stripe between the upper and midlateral red stripe (this is always white in T. rubrovittatus).

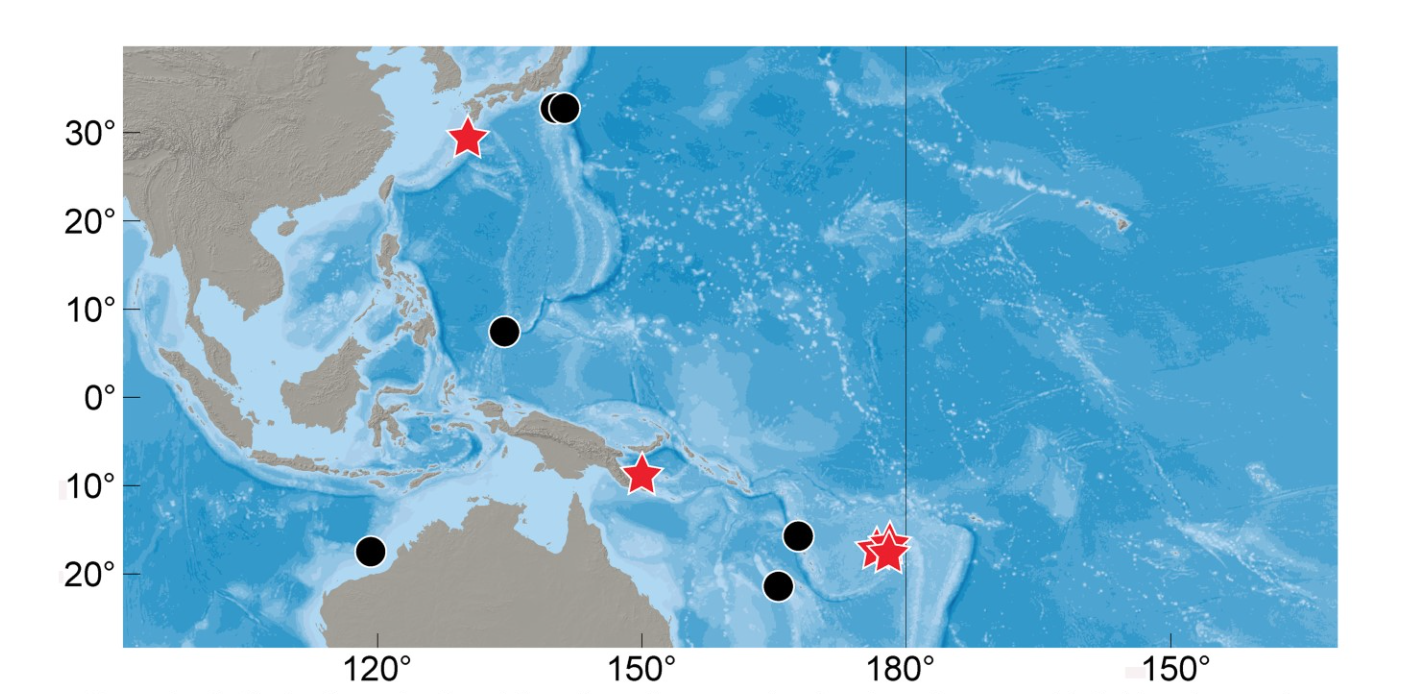

Distribution of T. rubrovittatus (black) vs. T. dewapyle (red). Photo credit: Fukui & Motomura 2015.

The biogeography for both species overlaps significantly, with T. dewapyle maintaining its distribution within the western Pacific Ocean from Japan, Papua New Guinea, Fiji and Indonesia. It is epibenthic, preferring sandy bottoms replete with rubble, with individuals sometimes found in a small harem. It is most commonly seen at depths of 65-70m, although it can occur as shallow as 20m. T. rubrovittatus on the other hand, is found in Japan, Palau, north-western Australia, New Caledonia and Vanuatu. The specific epithet dewapyle is a conjunction of the surnames of Shin-ichi Dewa and Richard Pyle, both of whom collected all the type specimens of the new species.

With the western Pacific phenotype now officially described and out of the way, what is left to be done with the Indian Ocean representative? Perhaps in due time, this species will too be elevated to species level.

The full paper is available on Zootaxa.

References:

Fukui. Y & Motomura. H (2015) A new species of deepwater wrasse (Labridae: Terelabrus) from the western Pacific Ocean. Zootaxa 4040 (5): 559-568.

Hi Lemon, Nice accounting! One thing I’d like to mention is that at this level of species delineation, it is really a matter of opinion. The authors of T. rubrovittatus were well aware of the phenotypic differences between the two type specimens (one from New Caledonia, one from New Guinea). In their opinion, however, these differences were not sufficient to warrant recognition as distinct at the species level. The important point here is “opinion”; there are no absolutes in species boundaries. Evolution does not produce “species”; rather, the products of evolution are populations of organisms with varying degrees of historical gene flow. At some arbitrary point in evolutionary time, the gene flow between populations becomes low enough, and phenotypic/genotypic variation sufficient enough, that a competent taxonomist decides that communication is best served through labeling the populations with different specific epithets. However, competent taxonomists may disagree with each other. As in politics, some tend to be more conservative (“lumpers”), and some tend to be more liberal (“splitters”). Hence, there was no confusion or mistakes made when T. rubrovittatus was described, nor was there confusion or mistakes when T. dewapyle was described, nor would there be confusion or mistakes if someone later decides to synonymize T. dewapyle with T. rubrovittatus. It’s all just a matter of opinion in such cases. In this particular case, I’d be very curious to know what the genetic patterns are like, comparing specimens from New Caledonia with populations elsewhere in the western Pacific (note: New Caledonia is also in the western Pacific, and not too far from locations where T. dewapyle lives). Are there any other specimens from New Caledonia we can use for comparison? We’ve seen Terelabrus on deep reefs all over the Pacific, and a lot of the variation in color seems linked to body size (particularly the barred pattern on the stripes, and the amount of yellow). Don’t get me wrong: I’m extremely delighted and honored to be included in the name of the newly described species; and I do sincerely hope further research supports the case that communication is best served by having two different names to represent the different populations. But no matter where it ends up, just keep in mind that species distinctions at this level are really matters of opinion, not right or wrong in an absolute sense.

Hi Richard!

Thanks for the reply. I wasn’t aware that the authors knew about the differences in phenotype. I was just recounting Fukui and Motomura’s paper here, without my own opinions on the topic. I agree with you on opinions regarding what defines a species. I’ve been writing a series of articles on Cirrhilabrus with a friend, forming our own insights and hypotheses on the phylogenetic classification, and even within that there are plenty of inconsistencies on how the various taxa are treated. what defines a “species”, and how the various complexes and groups are being dealt with varies across the board by different taxonomists. In that sense, there are a lot of things i agree and disagree with as well. And as you said, based on opinions! I hope you have a chance to read that. Have fun with Brian on NOAA! He’s been sharing the adventures on Facebook.

Thanks, Lemon — I agree! Alas, such is the nature of taxonomy, as we try to force-fit the heterogeneity of biodiversity into our nice little “species” boxes. The more we learn about it, the more muddled the species boundaries become. Still, it’s a useful exercise to categorize life in a way that allows us to more or less communicate with each other. Incidentally, I was looking at some video I took in about 115m in Fiji, and there is a group of what look a lot like T. rubrovittatus. So, perhaps either both species occur in Fiji, or the differences are more about juveniles vs. adults (the fish in the Fiji video are large, as are many of the T rubrovittatus specimens; whereas all specimens of T. dewapyle are about 6cm or smaller). I’ll upload the video after I get off the ship tomorrow.

“Alas, such is the nature of taxonomy, as we try to force-fit the heterogeneity of biodiversity into our nice little “species” boxes. The more we learn about it, the more muddled the species boundaries become.”

Well said! So many species out there with phenotypes that blur the lines of what defines a species. It’s such an arbitrary term. Some of them forming a seemingly continuous spectrum of phenotypes from A to B. What do we call those in the middle? Never easy!

Looking forward to that video! And as always, happy diving!