One of my favorite exhibits to take care of at the Long Island Aquarium is our frogfish exhibit. It’s a small focus display of around 36 gallons and is home to four personable frogfish: one Antennarius maculatus, one Antennarius pictus and two Antennarius commerson.

The genus Antennarius contains 13 different species of frogfish. These frogfish can be found in both tropical and subtropical water; they spend most of their time in the benthos zone or floating around in Sargassum.

Besides their unusual appearance, frogfish also have another unique adaptation. Since they aren’t quick swimmers, these fish need to be able to capture prey (their diet is mainly fish and crustaceans) in a different way. They are able to do this by using a rod (called an esca) that has a lure (called an illicium) on the end. These lures can come in all shapes and sizes, but they all function the same way – the lure resembles the food their prey eats – animals like worms, small shrimps or small fish. They can consume a prey that is up to twice their size.

The habitat that the frogfish comes from will effect the type of lure it has; species that live in coral and sponges often have a long lure, as they need to attract their prey from a distance, while those that live in rocky crevices generally have a short lure, because its prey will pass much closer by. Each species moves their rod and lure in a pattern specific to that species. For example A. maculatus moves its rod and lure in wavy patterns, while A. commerson moves in an up and down pattern.

Frogfish can also use chemical attractants to capture prey. This can be a key survival tactic for species such as A. striatus, who forages at night. This species can also enlarge their esca by up to 30%.

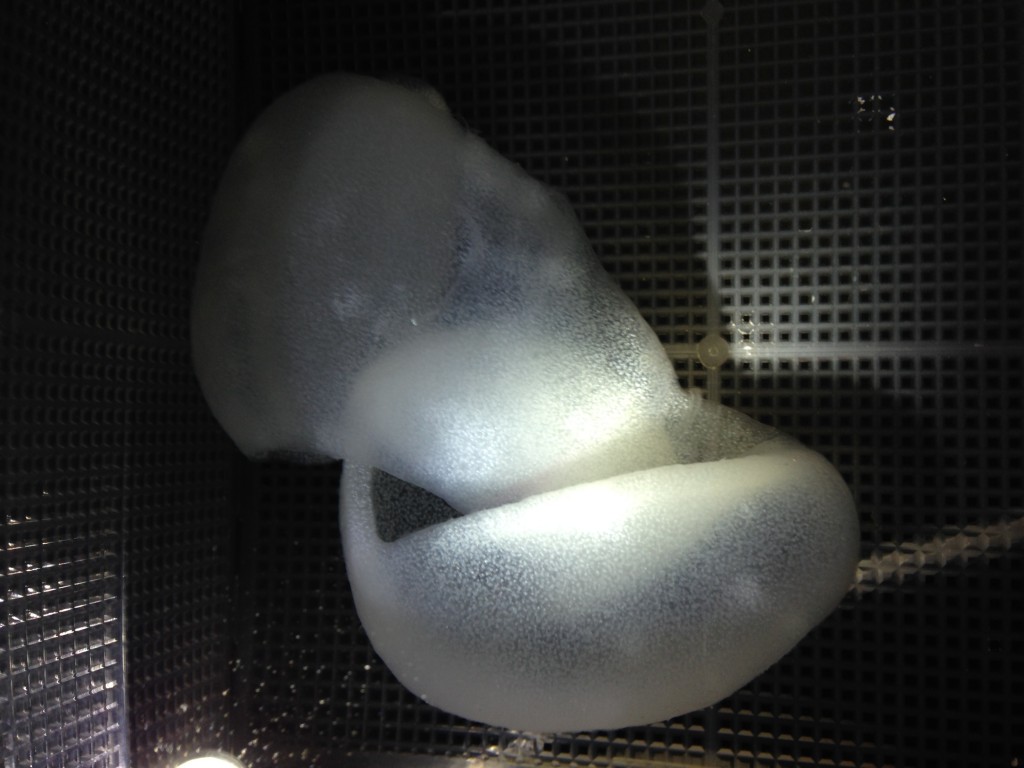

The breeding habits of the frogfish are quite interesting, though not a lot is known about frogfish spawning. From what has been documented, the courtship begins anywhere from a few days to just a few hours before the spawn. When spawning begins, the male follows behind the female, just below her cloaca; as she releases her eggs, the male swims around in a swirly pattern, fertilizing the eggs as he goes – the whole process takes about 5 seconds from start to finish. The released, fertilized eggs are encapsulated in a ribbon-like mass called an epipelagic egg raft, which drifts along at the surface of the water for several days and can cross large geographical distances. As the eggs hatch, they release the fish larvae – some of the smallest I have ever seen. So far, only one species of frogfish has been captive bred to date: Rhycherus filamentosus, Tasseled Frogfish.

A frogfish egg raft from a spawning pair of Antennarius maculatus that are on display at the Long Island Aquarium

Frogfish have been labeled as being very difficult to care for, but I disagree. If you are able to obtain a good specimen, and take the time and effort to care for them, they can be wonderful aquarium inhabitants!

When it comes time to picking out the right specimen, it really boils down to three things: 1: Does the animal look healthy, or does it look lethargic, appear to have sunken-in eyes, or look like it has been injured? 2: Is the frogfish eating? Ask the person that you’re buying the fish from to feed it; does it seem interested and does it actively hunt? Are they feeding it live food, or have they weaned it onto a frozen diet? Have they tried offering anything other than live food, and if not, what are they using to enrich the food that is being given? 3: Is this animal the correct size for your care? I recommend starting with a specimen that is at least 4″. This ensures that you can offer the animal a variety of different foods. If the frogfish is too small, it may not live very long; it has dealt with the stress of being collected, transported, and starved for days on end, and now it is sitting in a pet shop. That’s not to say you aren’t capable of nursing the animal back to health, but is it worth the risk? That animal, sadly, may already be past the point of no return.

Before you go to your local fish store to pick out a specimen, there are a few things you need to do to prepare for the new arrival. First, you should set up a proper quarantine system. Like all QT systems, tank must be the proper size, with adequate filtration, and have been fully cycled. You need to provide a few extra hiding spots for the frogfish; they are slow and don’t move much, and you want them to feel safe and secure. This will help reduce their stress, and will help when they begin to feed. The hiding spots you have added need to be in a low flow area; since frogfish are not great swimmers, they can easily get caught up in a current, and may get injured.

Like all animals, frogfish are susceptible to disease. It is best to have all the medications you may need on hand before bringing a new animal home. If your new fish has parasites, I recommend dosing with chloroquine to combat the outbreak. In my experience, frogfish do not do well with most copper treatments; chloroquine is a gentler option. For more information on chloroquine, I suggest reading Jay Hemdals article on it here.

Frogfish do best at temperatures between 70-76 F, and at a salinity level between 30-34 parts per thousand.

Make sure that you have the proper food to feed your new frogfish; some might eat frozen foods right off the bat, but most of the time, a newly-acquired frogfish will require live food. Unless you are purchasing a very small frogfish (which I do not recommend unless you have plenty of experience) you should offer rostrum-less grass shrimp; removing the rostrum protects the fish from potential internal injuries. Make sure that the grass shrimp are properly enriched with either some sort of frozen cyclopoid or a live copepod/artemia. You can offer your frogfish live fish such as saltwater mollies, but don’t feed them too many, as that could lead to fatty liver disease. For frozen foods, I recommend either sandeels or silversides, both of which can be easily obtained.

Once you have brought your new frogfish home and carefully placed it into the quarantine tank, you might notice that the frogfish is breathing very “heavy”. This is due in part with the frogfish using its gills to control its buoyancy. Frogfish have particularly interesting gills; they are found directly behind their pectoral fins.

Let the frogfish settle into its new QT system for a day or two, and then offer it some food. If the store was feeding it live food, you will need to as well, until you are able to wean it off onto frozen. Offer 2-3 enriched grass shrimp per frogfish every other day until the animal looks like it has gained weight, but be wary of over feeding, since frogfish can be very susceptible to fatty liver disease. Frogfish are also notorious for “begging” – their mouths may be big, but their eyes are much bigger. Once the frogfish is gaining weight, begin to offer it frozen food. I start with pole feeding my fish frozen sandeels, wiggling each one in front of their faces to entice them. They usually begin feeding on sandeels fairly quickly, and once they accept it readily, I begin to offer a variety of foods such as silversides and krill. I also continue to feed live grass shrimp every once in a while, to encourage hunting habits. Here’s a video of our frogfish getting fed a sandeel.

And here’s a video of our frogfish eating a grass shrimp:

I hope that you have learned a thing or two about frogfish, and that after doing a bit more research you will try your hand at keeping one. Remember, there is no fish that is impossible to keep; what may seem impossible is really just something you haven’t acquired the experience and knowledge to do yet. Keep things fun, and most importantly, keep things simple.

@Aquaristman Cool article Noel