While studies and surveys conducted on piscine organisms often involve in situ research on living specimens, a great deal of it occur post mortem. In science, death is the gateway of knowledge, and only in death can an animal be picked apart and studied in depth, revealing secrets pertaining to everything from its morphology to genetics. It’s a necessary loss, and often times, a voucher specimen reveals more that there is to know dead, than alive.

But to really reveal the unabashed truth that lay hidden in an organism, one must first prepare it for study. In fish, this often involves a multi-step process to properly fix and preserve it for long term storage. Ideally, you want something that will last long enough for the duration of your study, and for the study of others; and not a putrid pile of rotting flesh.

A freshly dead sample mounted and spread with pins on a styrofoam board. These pins are a little too big, and ideally, entomological pins should be used. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

In a freshly dead (or euthanised) specimen, the muscles and tissues are relaxed and pliable enough to work with. This is different in the later few hours of death, where rigor mortis sets in due to the very complex chain reaction of ATP depletion and calcium ion uptake in the cells. Preparation of samples are usually done before this stage. In fish, important anatomical features such as fins are spread out, allowing for ease in examination and counts pertaining to the number of spines and rays. Entomological pins are used to keep the fins in place, and it is important to try and spread them out as wide as you can. To keep them in this position, formalin (37%) is painted or dripped over the specimen and allowed to set for a few minutes. Once fixed, the pins can be removed with minimal damage to the specimen.

It is important to photograph the fish now, in its still fresh live coloration, as this will later change drastically during preservation. Photography should be carried out with the specimen just barely submerged in water, so as to prevent any reflection from the moist skin or scales. The background should not be distracting, allowing for the features to be elucidated clearly. White or black backgrounds work well.

The specimen, after photography, should be left to immerse in formalin for at least a week. In large specimens, formalin could be injected into the body cavity to prevent decomposition from the inside. Formalin will fix and strengthen the tissue, and sets the specimen for long term storage. It should be noted that in genetic studies, samples tainted with formalin are usually rendered unusable, as formalin is well known to destroy DNA molecules. For genetic studies, direct preservation in ethanol is sufficient. After the initial formalin treatment, the specimen will now be rather stiff, and the fins and membranes no longer pliable. Some color loss is to be expected here. As long term storage in formalin will destroy the specimens (due to its acidic nature), they will have to be transferred to a more neutral medium.

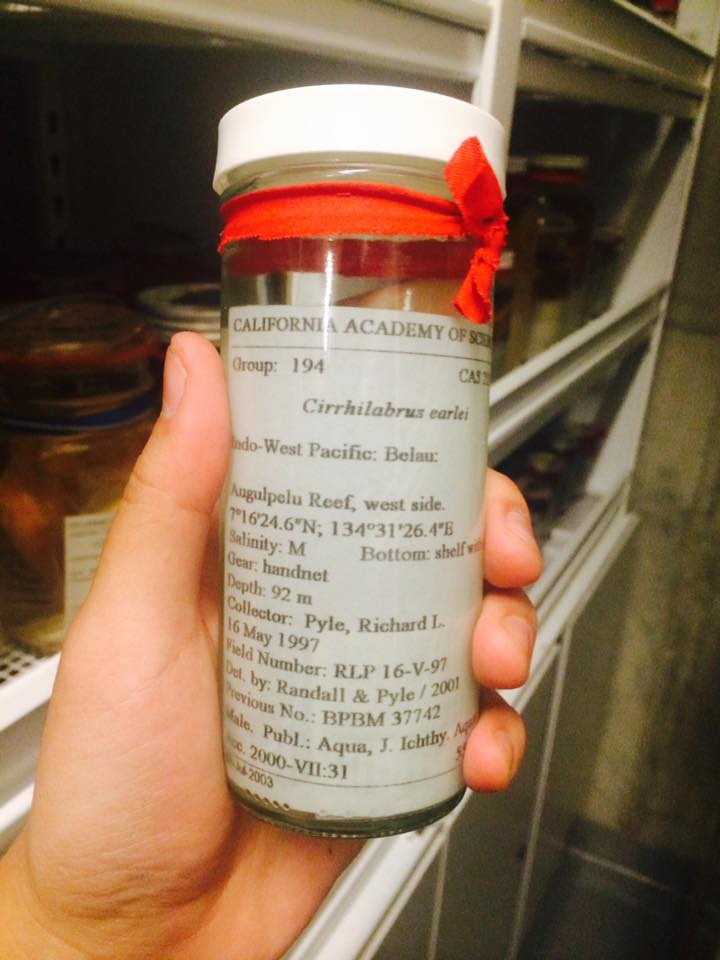

For long term storage, 75% ethanol is recommended. The specimen is first rinsed with distilled water to rid it of residual formalin (and the nauseating smell), before it is transferred. Staging can be done, where specimens are gradually placed in ethanol of increasing concentration before the final (75%) storage. This helps to rid any stubborn formalin residues as well. You’ll notice that in ethanol, the specimens lose whatever remaining color almost immediately. After a day or two, and depending on the species, they fade to a ghostly tan or white. Here, it is important to take a second photograph, to document the color in alcohol. It is also important to record all necessary information pertaining to the specimen. Date of collection, date of preservation, name of specimen, location, depth, collector etc, are all useful information. Remember, a specimen is useless without a label.

Cirrhilabrus earlei at the California Academy of Science. The red ribbon denotes that this specimen is the holotype. Note the information present on the label. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

Now that the specimen is fixed, photographed and preserved, it can be subjected to a wide array of studies. Morphometric measurements and meristic counts, X-ray radiographs, tissue or osteological staining and a whole array of other procedures can all be carried out on the prepared fish. For important specimens, namely holotypes and paratypes, these are stored in museums or scientific institutions around the world, where they are assigned a code starting with the institution’s initials as the prefix, and an assigned number as the suffix. e.g, XYZ 12345. Just like you would a library book, these specimens can be transferred on loan to other institutions who may need access to a particular specimen for study, and the institution codes serves as reference numbers tagged to a particular specimen.

Dr. Luiz Rocha, ichthyological curator at the California Academy of Science, surrounded by jars of preserved fish. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

The briefness of this article just hints at what goes on on the other side of science; the science where death is the precursor for knowledge. It’s not all grim and melancholic, and as you can see, scientific and taxonomic advancements are nothing without the loss of a voucher specimen. To sacrifice an organism to learn about it, to conserve and to protect it is a necessary sacrifice. And it’s not the end of its road. It’s merely the beginning.

0 Comments