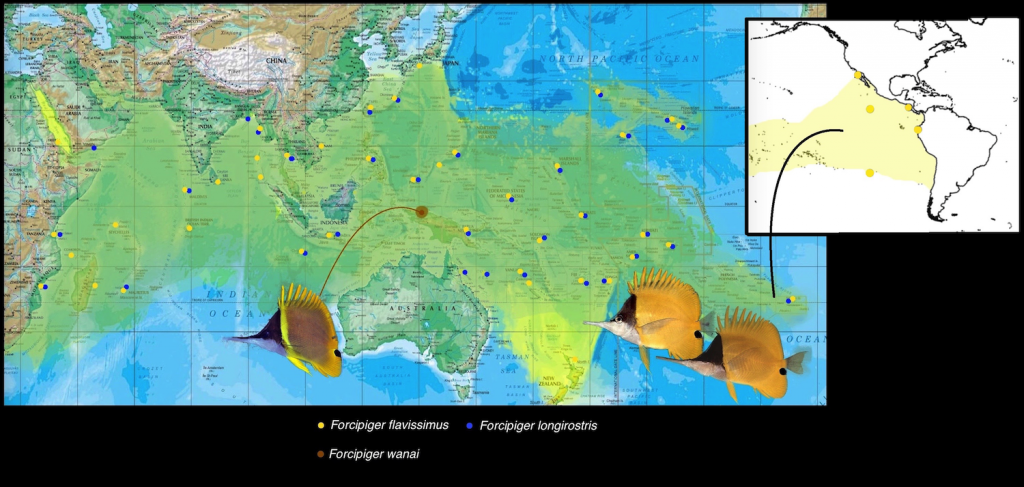

Biogeography of Forcipiger. This genus is remarkable for the dichotomizing distributions of two species. F. flavissimus is the most widespread butterflyfish in its genus and family, adopting a nearly completely circumtropical distribution. F. wanai, on the other hand, is restricted to only Cenderawasih Bay and the surrounding region of West Papua. Photo credit: Gerry Allen and John Randall.

Of the butterflyfishes that have evolved long snouts in tandem with their dietary needs, none are more impressive, or quirky, than those in the genus Forcipiger. This genus boasts some of the most iconic members of the family, easily identified in the field by even the most amateur of divers. My mother, for one, surprised me one day by identifying it correctly in a travel brochure (the fish was featured in a dive resort advertisement). Considering that she knows as much about marine fish as I do folk dancing, it comes as no surprise then, that Forcipiger has managed to attain more or less a symbolic status even amongst the general public.

The genus comprises three species, of which, two are remarkable for their dichotomizing and polarizing biogeography. F. flavissimus is the most widespread butterflyfish, not only in its genus, but in the entire family. Conversely, F. wanai is localized to the reefs of Cenderawasih Bay and regional West Papuaa – a tiny locale in the Indonesian Archipelago. The nearly circumtropical distribution of F. flavissimus is extremely remarkable, where it can be found from the East African coast all the way to Baja California in North America. Aside from crossing into the Eastern Pacific, it has also managed to colonize Norfolk Island in New Zealand. F. flavissimus is absent in the Atlantic, due to its inability to cross the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. The strong, cold currents present here separates the Indian Ocean from the Eastern Atlantic and prevents species such as F. flavissimus from attaining a fully circumtropical distribution (although there is no doubt that it will proliferate in the Atlantic given a chance – alien introduction).

The reason for Forcipiger’s success is its long larval phase, allowing them to drift significant distances to colonize new ground. F. flavissimus is reported to settle out of its larval phase at 7 centimeters, after which it quickly adopts the usual yellow coloration and begin its life as a juvenile. This is comparatively similar to Moorish Idols of the monotypic genus Zanclus, and, in comparison to Zanclus’ biogeography, you’d notice that it too, attains a nearly circumtropical distribution. If you ever wondered why you’ve never seen a “baby” Forcipiger or Zanclus, now you do. Juveniles are smallest at 7 cm.

Relative comparisons of snout lengths in F. flavissimus (above) and F. longirostris (below). Note the remarkable difference in length. Snout length vs. SL = 31.4%. Photo credit: Ichthyologist.tumblr.

Relative comparisons of snout lengths in F. flavissimus (above) and F. longirostris (below). Note the marked difference in length. Snouth length vs. SL = 38.8%. Photo credit: Ichthyologist.tumblr.

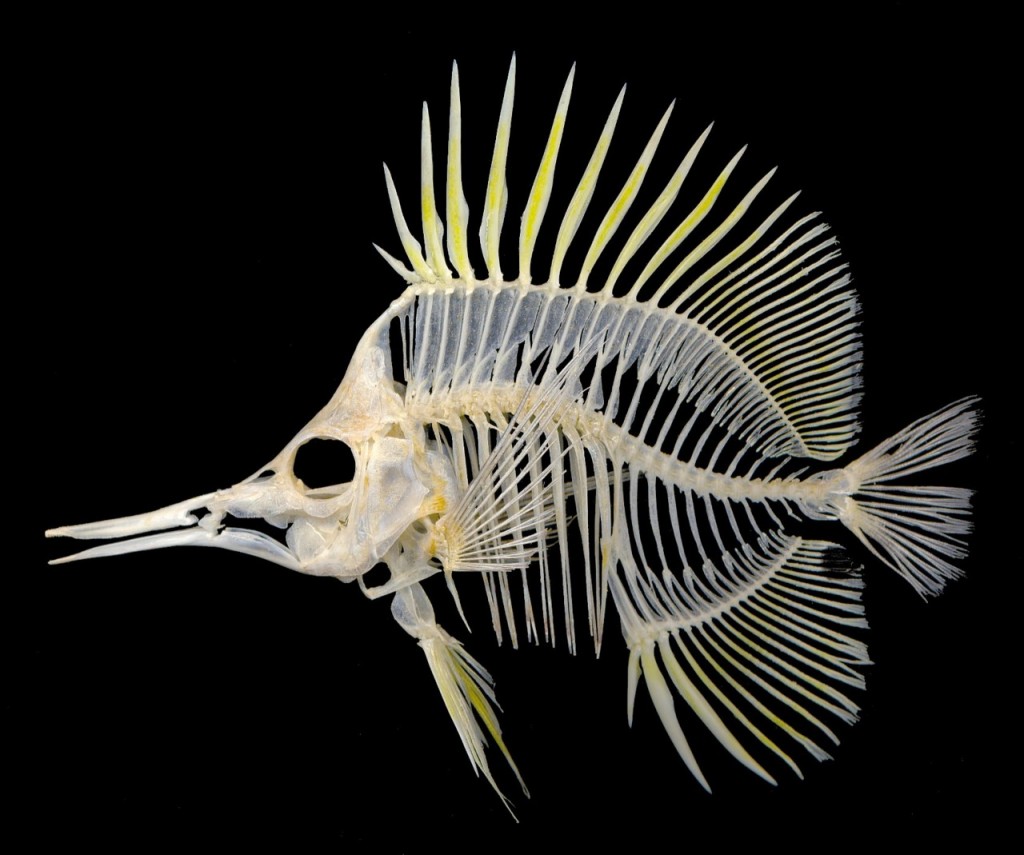

Forcipiger is easily diagnosed. All species are yellow in their ground coloration, delimited from their transverse, bicolored heads. Their snouts are perhaps the most diagnostic, being extremely long and needle-like. These are used to poke deep into cracks or holes where they forage for worms and other invertebrates. Indeed, with this remarkable mouth, Forcipiger are quite adept at removing even tubed worms from their protective sleeves. In fact, the generic epithet “Forcipiger” is literally translated from the latin for “forceps carrier”, a very apt and descriptive name. But, unlike Chelmon, Forcipiger are strictly reef associated, and is rarely found in turbid coastal waters. Instead, they prefer the usual coral associated reefs in shallow waters – although they can also be found at depths exceeding 200ft.

Melanistic Forcipiger longirostris photographed in Hawaii. Photo credit: Bruce and Jacky, Hawaii’10.

The taxonomic status of Forcipiger has, in the past, been the subject of some confusion. The species herein are remarkable not only for their biogeography and morphology, but also for their proclivity in possessing two distinct color phases – melanistic and leucistic. These have been mistakened in the past as distinct species, but it has since been revealed that these are just aberrant forms of the usual F. flavissimus and F. longirostris. In particular, the melanistic forms of the two species were regarded as F. cyrano and F. inornatus – both are now unaccepted junior sysnonyms. Melanistic individuals range from jet black, to yellow with varying fuliginous obfuscation over the entire body. This spectrum of intermediates further disproves F. cyrano or F. inornatus as being legitimate taxa. The phenomenon occurs when the dark pigment melanin is over-produced. Strangely, these hyper pigmented specimens are unable to maintain their color in captivity, fading back to the usual yellow in a matter of days to weeks.

In contrast, leucistic morphs are either completely, or partially white over most of the body. This affliction is not to be confused with albinism. In leucism, organisms produce reduced pigments of multiple types – not just melanin. This often results in a white or pale, patchy coloration. Individuals with a patchy distribution of white over the otherwise normal body coloration may be deemed as piebald. In contrast, albinism occurs due to the complete lack of melanin production, and is characterized by having red eyes (due to the blood vessels now visible from the decolorized retina). Leucistic animals, on the other hand, have regular colored eyes. Like melanistic individuals, leucistic forms are also unable to retain their peculiarity in captivity. How or why this occurs is still not known.

The number of species in Forcipiger now stands at three, elaborated in slightly more detail in the following accounts.

Forcipiger flavissimus

In F. flavissimus, the ground color is a uniform and featureless chrome yellow. A single black ocellus is decorated on the edge of the anal fin, just below the caudal peduncle. Both dorsal and anal fin termens are edged in a hyaline cloud-blue margin. The head is laterally bicolored – black on the upper half, and silver below. This delimitation in color transects through the eye, which serves as one of a few minor differences to F. longirostris.

The pectoral fins are translucent and unusually large, being wing-like and stretching to at least half its body length. The upper rays are significantly longer than the lower, and taper off in a sharp point. The caudal fin is also slightly pointed on the upper lobe. This species occurs in a melanistic phase, which occurs not uncommonly on certain Hawaiian Islands. Despite its dramatic difference in color, it is often seen paired with regular yellow individuals.

As discussed in the introduction, F. flavissimus is almost completely circumtropical in distribition, being absent only in the Atlantic. It is found on almost every reef of the Indian and Pacific Ocean, from the East African coast to Baja California. It also occurs in the Red Sea and Norfolk Island. In deeper waters, especially in the twilight zone, F. flavissimus is observed to swim upside down or vertically against ledges and steep slopes. It displays this behavior less frequently in shallow water. This species is extremely rare in Cenderawasih Bay, where it occurs with two other members of the genus.

F. flavissimus is common in the trade, and retails for rather reasonable prices. Despite its dainty appearance, the species is very hardy and accepts most regular aquarium fare, provided they are small enough to be picked on. Frozen foods such as brine and mysis shrimp are perennial favorites.

Forcipiger longirostris

Forcipiger longirostris, Marshall Islands. Note the spotted breast and fully blackened eye. Photo credit: Dustin Dorton.

Forcipiger longirostris is essentially identical in coloration to the preceding species, except that its entire eye is black and not delimited by the lower half in silver. It possesses on its chest, a series a fine striae comprised on tiny dots. This feature is further diagnostic of F. longirostris. As its specific epithet would suggest, F. longirostris has a significantly longer snout than F. flavissimus. This difference can be up to 10% in fully-grown specimens. The snout length is proportionate to its size, and increases in length as it matures from juvenile to adult. Like F. flavissimus, this species settles on the reefs at a very large post-larval size, which would explain its extensive biogeographic distribution as well.

F. longirostris is sympatric with F. flavissimus across its entire range with the exception of the Red Sea, Norfolk Island and the Eastern Pacific. It reaches its easternmost limit in the Polynesian Islands (Pitcairn group). Why these two species are so broadly sympatric is quite curious. It would seem, with the longer snout length, that F. longirostris has evolved to feed on more specific prey in harder to access regions on the reef. This, however, has not been extensively studied, and remains only as a hypothesis.

Forcipiger longirostris from Hawaii. Note the striae present behind the pectoral fin. Photo credit: Barry Fackler.

Unlike F. flavissimus, F. longirostris displays at least one geographic variation in the isolated region of the Hawaiian Archipelago. Here, specimens sport an additional series of lineated spots behind the pectoral fin. It is not known if this phenotype represents a hidden, cryptic population. It is unusual for widespread species to display any cryptic species, as the long larval periods enable genetic connectivity in all regions of their distribution. This is seen in species such as Zanclus canescens, Xantichthys mento and Acanthurus nigricans. However, although uncommon, cryptic speciation is not unheard of in such scenarios, as can potentially be seen in Acanthurus triostegus. A. triostregus shares pretty much the same biogeography as Forcipiger, but shows phenotypic variations in certain island groups across its range.

Whether or not the Hawaiian population of F. longirostris eventually turns out to be a cryptic species or nothing more than a color variation is subject to further studies. Extensive molecular sequencing might prove useful here. The isolation of this species in the region of West Papua has, however, succeeded in splitting F. longirostris into a second species. This will be touched upon later in the article.

Like the preceding species, F. longirostris also occurs in a melanistic phase, which varies in its extensiveness and intensity. In addition, a leucistic phase is also well documented in this species, and, like its melanistic phase, varies in its general appearance. Both aberrations are very transient in captivity, and are not known to be long lasting.

A heterospecific pairing between F. longirostris (left) and F. flavissimus (right). Note the difference in snout lengths and eye color. Also note the relatively large size of the pectoral fins in members of this genus. Photo credit: Dustin Dorton.

F. longirostris is less frequently encountered in the field. This is also translated into the aquarium trade, where it occurs as a rarity. Unlike F. flavissimus, F. longirostris is significantly harder to feed. This could be due to its longer and smaller mouth, in turn requiring smaller foods and more frequent feedings. This is likely supportive of its more specific diet in the wild, acting as a selection pressure for its evolution away from F. flavissimus. Both species have been documented to form heterospecific pairs, which would suggest hybridization in the wild. However, because of the similarities in both species, hybrids, if ever found, would prove rather difficult to diagnose based on their weak intermediate phenotypes.

Forcipiger wanai

Forcipiger wanai with its exceedingly rare melanistic phase in the background. Photo credit: Richard Smith, ORI.

This, the last of three members in the genus, is also the newest. F. wanai was described in 2012 on the basis of slight differences in coloration, genetics and meristics. The species is similar to F. longirostris, but is slated in a dark brown suffusion over the body. F. wanai also differs from F. longirostris in pectoral rays (15 vs 16) and lateral-line scales (mean 60.8 vs. 67.6).

F. wanai is restricted to the Cenderawasih Bay region, as well as Raja Ampat in West Papua. The biogeography of this region is very unique and relatively well studied. Endemism here is reported to be higher than the rest of the Indonesian Islands. This is due to the formation of the bay area over the past fifty million years. According to Hill and Hall’s (2003) paleoreconstruction model, a series of island arc terranes arose along the edge of the Caroline Plate, eventually colliding with the Australian Plate, and then sliding parallel to the northern coast of New Guinea before eventually accreting to form the northern ranges.

One of these arc terranes known as the Tosem Block (Hill and Hall, 2003) slid across the entrance of the Cenderawasih Bay between two to five million years ago, before finally stopping just at the northern edge of the Bird’s Head Peninsula. This isolated the region, restricting movement into and out of the bay and setting the stage for allopatric speciation. The shifting of plates work in tandem with the region’s fluctuating sea levels, further amplifying the allopatric isolation and promoting the rich development of unique species within the Cenderawasih Bay area. Forcipiger wanai is one of many of such fauna found nowhere else on earth. It, however, swims with F. longirostris and F. flavissimus (where it is extremely rare) here. Strangely, the latter is seemingly unaffected by this geographical isolation.

F. wanai also occurs in a melanistic form, where it is significantly rarer than those of F. longirostris. Gerry Allen reported seeing one in at least a hundred specimens in Cenderawasih Bay. F. wanai is unobtainable in the trade. The specific epithet “wanai” refers to its name in the Wandammen language for this species.

In summary, Forcipiger is a fascinating genus with some members exhibiting extremely wide distributions across the world’s oceans. Although generally largely unaffected by the evolutionary pressures of geographic isolation, this is untrue for at least one population of Forcipiger in the West Papuan region of Cenderawasih Bay. Whether or not further evidence of cryptic speciation occurs in this genus will have to be revealed via extensive molecular study. This sums up the discussion of one of my favorite butterflyfish genera, apart from Chelmon. In the next installation, we take a look at the genus Prognathodes, which presents us with some of the most challenging biogeographic and taxonomic scenarios in Chaetodontidae.

0 Comments