There are a great many fishes found in shallow tropical waters that remain unavailable to aquarists, but few are as beautiful and recommendable as the signalfishes. These small, peaceful bottom-dwellers are ornately patterned, vibrantly colored and exhibit some endearing behavioral quirks, yet, due to their penchant for deep sandy habitats, they have been entirely ignored by aquarium collectors and, even amongst zoologists, the group remains something of a mystery.

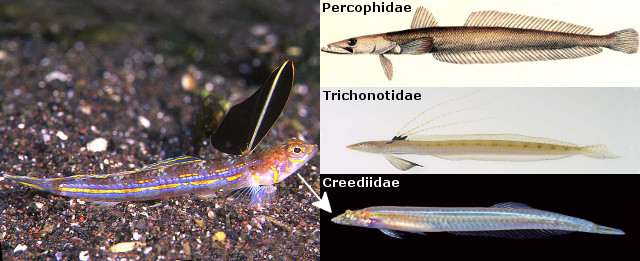

Much of the obscurity surrounding these fishes has to do with our poor understanding of their place in the grander scheme of fish evolution—just who is it that they are related to? For a while, they were lumped into the heterogenous family, Percophidae, whose members shared general similarities of fin and body shape. Later, it was thought that they possessed certain morphological nuances with the sanddivers (Family Trichonotidae) and were reclassified there, but more recent molecular study has changed things around yet again.

Signalfishes have now been elevated to their own family (Hemerocoetidae), sister to another obscure group of tropical psammophiles, the sandburrowers, Family Creediidae. And, as it turns out, neither of these are of close relation to the sanddivers, as that family is in fact the sister group to the vast goby lineage. [For good measure, Percophis brasiliensis was found to be sister to certain Antarctic fishes called notothenoids, illustrating just how little we knew about the true evolutionary history of all these diverse fishes.] The take-home message from all this taxonomy is this: these are not gobies, even though they might sort-of, kind-of look like gobies.

Some oddball hemerocoetids. Credit: B. Hutchins/Western Australian Museum & Port Phillips Marinelife

Classification within the hemerocoetids remains fraught with challenges, as the group has yet to undergo any meaningful revision. Eight genera comprise the family, though only half of these contain more than a single species or two. These four species-poor taxa (Enigmapercis, Dactylopsaron, Matsubaraea, Squamicreedia) are seldom encountered and have restricted ranges, often in subtropical or deepwater habitats, while the five species in Hemerocoetes are found in deep waters around New Zealand and are recognizable for lacking the spinous dorsal fin.

The remaining three groups—Pteropsaron, Osopsaron, Acanthaphritis—tend to be more colorful and are generally found closer to shallow-water reef habitats, though always on sandy substrates. They share a distinctive, albeit microscopic, spine projecting forward on the upper jaw (=maxillary), but precisely how the sixteen currently recognized species in this lineage are interrelated is a matter of conjecture, as the traits which have been used to diagnose these three groups appear increasingly unreliable and genetic data is yet lacking.

Acanthaphritis (4 spp.) and Osopsaron (2 spp.) are known exclusively from trawled specimens collected at 100-350 meters in the Pacific Ocean. Most species have scales present beneath the eye and show little sexual dimorphism in the first dorsal fin. Obviously, because of the considerable depth they occur at, these fishes are unlikely to ever find their way into an aquarium, but the live coloration, where known, is apparently rather attractive, consisting of a row of bright yellow spots along the midline (though there doesn’t appear to be a single decent photograph of a live specimen to properly illustrate this).

The species of direct consequence to marine aquarists are those classified in Pteropsaron, as these are the most colorful and shallowest dwelling in the family. Still, only four of the recognized taxa are commonly encountered by SCUBA divers, with the other species found at relatively inaccessible depths, including: P. heemstrai (East Africa, ~150m), P. natalensis (East Africa, ~70m), P. levitoni (Philippines, ~80m), P. dabfar (Philippines, ~80m), P. neocaledonicus (New Caledonia, ~300m), & P. incisum (Hawaii, ~150-250m).

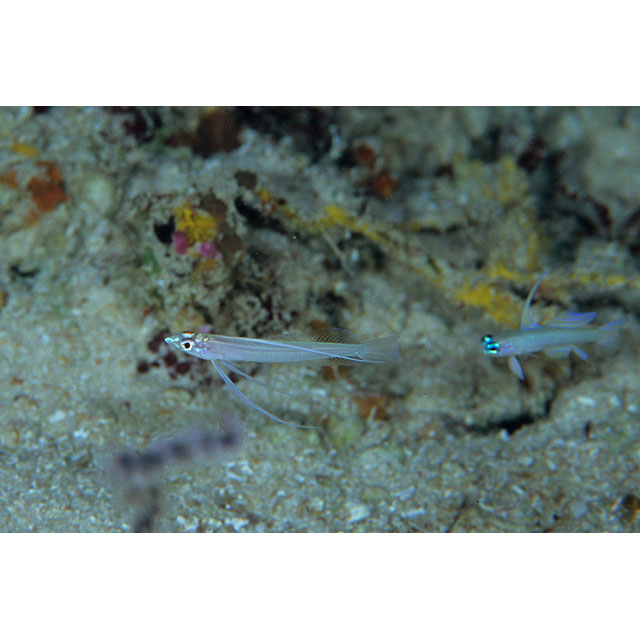

- Anilao, Philippines. Credit: Guts Diving Club

- Anilao, Philippines. Credit: Guts Diving Club

- Philippines. Credit: Andrey Ryanskiy

- Philippines. Credit: Andrey Ryanskiy

- Mactan, Philippines, 22 meters. Credit: Oceanus

- Kashiwajima, Japan, 10 meters. Credit: pisces_kazu

- Kashiwajima, Japan, 10 meters. Credit: pisces_kazu

- Cebu, Philippines. Credit: umioniyome

- Cebu, Philippines. Credit: umioniyome

- Cebu, Philippines. Credit: Takako Uno

- Cebu, Philippines. Credit: Takako Uno

- Sabah, Malaysia, 30 meters. Credit: F. Konno

- Cebu, Philippines, 22 meters. Credit: Garuda

- Bali, Indonesia, 50 meters. Credit: Michitoshi Uematsu

- Anilao, Philippines. Credit: nob@feeltheSEA

- Anilao, Philippines. Credit: nob@feeltheSEA

- Anilao, Philippines. Credit: Guts Diving Club

- Anilao, Philippines, 31 meters. Credit: Hiroshi Kobayashi

- Anilao, Philippines, 10 meters. Credit: Hiroshi Kobayashi

The species most likely to be collected for aquarists is the Pearly Signalfish (P. springeri), which is commonly encountered in the Coral Triangle in depths as shallow as 10 meters (though most specimens are found beyond 30 meters). It is readily identifiably by the red markings of the head and also by the pair of broken pearlescent stripes that form a series of dashes, with faintly visible vertical bars interspersed between them.

Like others in the genus, P. springeri occurs in small groups with a harem-like sexual structure and exhibits clear sexual dimorphism in the first dorsal fin—white & elongate in males, short and black in females. This fin is a highly modified structure unique to signalfishes, formed of 3-6 spines that meet basally in close proximity, allowing the entire fin to be waved about on a single rotating axis and used by males to communicate with each other in territorial disputes. In P. springeri, this fin has only 3 spines and is positioned just behind the head, anterior to the pelvic fins.

- Okinawa, Japan. Credit: unknown

- Okinawa, Japan. Credit: unknown

- Okinawa, Japan. Credit: unknown

- Okinawa, Japan. Credit: unknown

- Okinawa, Japan. Credit: unknown

- Kashiwajima, Japan. Credit: nob@feeltheSEA

- Okinawa, Japan, 75 meters. Credit: S. Ogawa

- cf springeri? Cebu, Philippines. Credit: Aquarius Divers

- cf springeri? Anilao, Philippines. Credit: moguri

- cf springeri? Anilao, Philippines. Credit: moguri

Another similar fish, which I will refer to as the Blueline Signalfish P. cf springeri, has been reported from Okinawa and Kashiwajima, Japan. It appears highly similar in its morphology but differs in having a complete blue stripe along the midline in both sexes, while the uppermost series of dashes is mostly absent. This fish is also considerably less-colorful, showing little of the red which marks the head and body of the true P. springeri phenotype. Unfortunately, few photographs seem to exist and I can find no discussion of it in any of the pertinent literature. Whether this indeed represents an undescribed species or merely a variation of P. springeri requires more study.

- Cenderawasih Bay, Indonesia. Credit: Gerry Allen

- Cenderawasih Bay, Indonesia. Credit: Gerry Allen

- Palau, 45 meters. Credit: Michitoshi Uematsu

- Palau, 30 meters. Credit: unknown

- Palau, 56 meters. Credit: Akihiko Mishiku

- Palau. Credit: ayumi

- Palau. Credit: ayumi

- Palau. Credit: ayumi

- Palau. Credit: e-photography

- Palau. Credit: nob@feeltheSEA

- Palau. Credit: nob@feeltheSEA

- Palau. Credit: nob@feeltheSEA

- Palau. Credit: uoharudive-palau

- Tinian, Mariana Islands, 60 meters. Credit: Junichi Otake

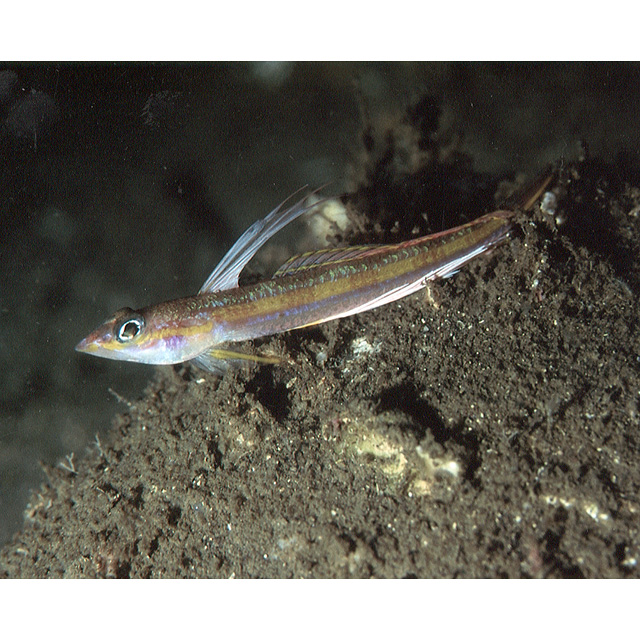

One other species in the genus possesses an elongated, 3-spined dorsal fin, the Midwater Signalfish, P. longipinnis, though in this fish the dorsal fin is situated further posteriorly (i.e. not before the pelvic fins). The most noteworthy difference, however, is seen in the greatly elongated pelvic fins, which results in this fish being unable to rest along the substrate. This epibenthic swimming behavior is unique amongst the signalfishes and gives it a particularly graceful appearance when floating about its sandy environs.

When P. longipinnis was described in 2012, it had only been recorded at great depth (~70 meters) in Cenderawasih Bay. The images included in this review considerably extends the known biogeography and depth range, with specimens now documented for Palau and Tinian, Mariana Islands as shallowly as 30 meters. Such being the case, this species could potentially be targeted for the aquarium market, as it would undoubtedly be a popular addition to smaller reef aquaria as a peaceful and beautiful shoaling fish.

- Osezaki, Japan, 8 meters. Credit: Hiroyuki Uchiyama

- Osezaki, Japan, 6 meters. Credit: 海たぬき

- Osezaki, Japan, 6 meters. Credit: 海たぬき

- Izu, Japan, 16 meters. Credit: Kenji Nin

- Osezaki, Japan, 8 meters. Credit: Hiroyuki Uchiyama

Easily the most well-documented member of this genus is the Blackfin Signalfish P. formosensis (often misclassified as a species of Osopsaron), a charismatic species known from the shallow subtropical waters of Japan, Korea & Taiwan. The common name is my own creation and alludes to the characteristic black dorsal fin of males. Unlike in the previously discussed species, this signalfish has five spines in the rather stubby dorsal fin of males, and, whereas most congeners have this fin at least partially white, this is an inky black with contrasting white spines in this fish. The video below illustrates how this fin is flicked about, up and down and side to side, in its territorial disputes.

https://youtu.be/QJAo8rUtb1g

This same region is home to another stunningly beautiful species, the Drapefin Signalfish P. evolans. It can easily be told apart from its sympatric sibling by the elongated white dorsal fin of males, as well as the hugely exaggerated anal fin (this latter feature is also seen in the African P. heemstrai). The two also differ in their patterning, with formosensis having two broken yellow stripes down the body and several similar oblique yellow markings on the head, whereas evolans has a single thick yellow stripe extending from tip to tail. Unfortunately, as both species are restricted to somewhat deep (20+ meters) subtropical waters in Japan, neither of these are likely to be made available to aquarists anytime soon.

- Osezaki, Japan. Credit: うっち

- Izu, Japan, 62 meters. Credit: Akihiko Mishiku

- Osezaki, Japan, 56 meters. Credit: Hiroyuki Uchiyama

- Osezaki, Japan, 60 meters. Credit: K. Kita

- Oseaki, Japan. Credit: Hiroyuki Uchiyama

- Osezaki, Japan, 52 meters. Credit: Hiroyuki Uchiyama

In all likelihood, there are more signalfishes awaiting discovery, both from SCUBA-accessible depths and from sandy habitats hundreds of meters deep. The species diversity of these fishes remains completely unknown for vast swaths of the tropical Indo-Pacific (e.g. Red Sea, Mascarenes, Maldives, Polynesia), though this is almost certainly an artifact of just how poorly studied their ecological niche is. While they may be somewhat challenging to find in their natural habitat, the many photographs included here illustrate that these are not inherently uncommon fishes in the wild.

With P. springeri being found at relatively shallow waters in the Philippines, it likely with be collected for the aquarium trade at some point once it’s realized that there might be a market for them. Hopefully someday soon it will be possible to recreate a signalfish biotope—a featureless sandbed replete with Tryssogobius, Myersina and Acanthocepola. While this may seem a far cry from the typical reef tank, perhaps it’s time the marine aquarium community expanded its attention beyond pretty corals and began to appreciate the wealth of biodiversity waiting to be explored.

Hello, very good and interesting review! Do you have a reference for the information about molecular data and the new family Hemerocoetidae? I’m working with a small quantity of larvae of Osopsaron karlik collected off Easter Island. Thanks in advance