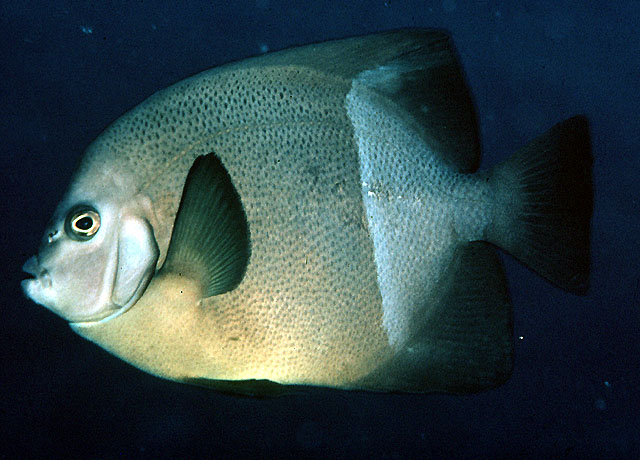

The rare and endangered Blaasop Beauty (Chelonodon pleurospilus) seen in captivity. Credit: Iwarna Aquafarms

The subtropical reefs along the South African coastline are a hotbed for many species of fish not normally collected for the aquarium trade. This biogeographically unique region is home to the famed Apolemichthys kingi—a resplendent fish of legendary rarity which is now sporadically available in the hobby. But there are many more interesting fishes to be had from these waters, and the aquarists at Iwarna Aquafarm in Singapore have recently hit upon an impressive collection from this rarely seen ichthyofauna.

The most exciting fish in this lot for me is an ornately patterned pufferfish known as the Blaasop Beauty. True to its name, Chelonodon pleurospilus is a stunning fish, with a series of olive-green bands dorsally, overlaid upon a background of fine spots and wavy stripes. However, I have to strongly question whether this is a species that should be exploited for the aquarium trade. The IUCN lists this fish as “Endangered”, stating that it is known from only five locations along a miniscule section of the South African coastline (the Xora River to Durban). In total, the available habitat for it is stated to be roughly 91 square kilometers (~56 square miles), or, to put it in perspective, this fish occupies a range smaller than the city of Joliet, Illinois. Now, ask yourself, if a species of pufferfish was endemic to Joliet, Illinois, would we be collecting it for the aquarium trade or, instead, doing all we could to protect it from the short-sighted greed of unscrupulous aquarium wholesalers?

Of less concern is the Doubledash Butterflyfish Chaetodon marleyi, which ranges from Mozambique to the western shores of South Africa. This attractive species sports three vertical bands on its sides, with bright yellow fins ventrally and a prominent ocellus dorsally. Specimens have been successfully kept in aquariums before and seem to present little difficulty in their husbandry (though cooler temperatures are undoubtedly of benefit longterm). Dietary study has indicated that terebellid polychaetes—the “spaghetti worms” found commonly in the sand of reef tanks—are the preferred diet in the wild, with smaller amounts of crustaceans, hydroids and tunicates rounding out the diet. For a benthic-picking fish like this, it’s probably unwise to place it in an aquarium with any sessile organisms.

The Dutoiti Dottyback Pseudochromis dutoiti is another rarity in captivity, though it is undoubtedly quite common in the wild, ranging from Mozambique and the Seychelles to South Africa. This species represents the African contingent of a widespread Indian Ocean species complex that includes the familiar Neon Dottyback P. aldabraensis and the Red Sea endemic Springer’s Dottyback P. springeri. Unlike those attractive species, the Dutoiti is a relatively drab fish, with muted colors that makes this the ugly duckling in this little dottyback family.

The Harlequin Goldie Pseudanthias connelli makes an appearance here too. Instantly recognizable for the curious half-banded patterning of the males, this fish forms the South African counterpart to P. fasciatus from the Red Sea and P. townsendi (=P. conspicuous) from Socotra, India and the Arabian Peninsula. While P. connelli is only known from a few scattered localities in South Africa, it’s likely this fish occurs at mesophotic depths throughout the eastern coastline of Africa. As with other deepwater and subtropical fishes from this region, cooler temperatures are a smart choice when keeping specimens in captivity.

And, lastly, we have a pair of angelfishes restricted to the Western Indian Ocean—the much-admired Apolemichthys kingi and the decidedly understated Old Woman Angelfish Pomacanthus rhomboidalis. This latter species is easily the least commonly seen of the many Pomacanthus out there, not so much for its restricted range in Southeastern Africa as for its muted coloration as an adult. Mature specimens possess a rather unique triangular shape on account of the dorsal and anal fins being rounded posteriorly, but the charcoal and grey vestiture donned by this Old Woman leaves much to be desired. Compared to the chromatic splendor of P. imperator, P. xanthometopon and even P. asfur, this fish is an utter failure at life. Genetic study has revealed it to be a close relative of the sympatric Yellowbar Angelfish P. maculosus, but it’s clear that somewhere along the way P. rhomboidalis fell from the ugly tree and hit every branch on its way down. I don’t often root for extinction, but if I had to choose one fish to kick the bucket…

0 Comments