The rarely seen P. carlhubbsi, at the Galapagos Islands. Credit: Mark Rosenstein

The distinctive deepwater butterflyfishes of the genus Prognathodes have been in the news recently with the exciting rediscovery of the enigmatic P. guyotensis, but, in general, this is one group that doesn’t get much attention from the average aquarist. While these fishes are often attractively patterned and easy to feed in captivity, they are only rarely available and exorbitantly expensive, leaving them better appreciated by the hardcore fish nerds and chaetodontid fanboys out there. Even the scientific community seems a bit disinterested with this genus, as the dozen or so species in the group have received relatively little study to date. We still know virtually nothing about how Prognathodes relate to one another, so let’s take a brief moment to summarize this butterflyfish biodiversity and ponder some of the biogeographical questions that surround them.

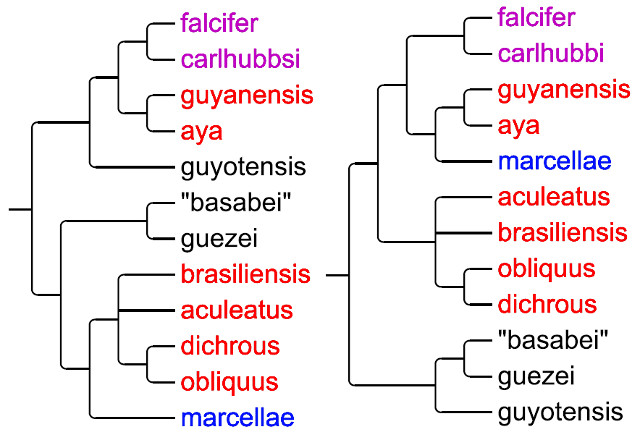

Proposed Prognathodes phylogenies: this study (left) & Tea 2016 (right). Purple=Eastern Pacific, Red=Western/Central Atlantic, Blue=Eastern Atlantic, Black=Indo-Pacific

While these butterflyfishes are all highly similar in their overall morphology, each possesses its own unique pattern allowing for easy identification. They occur in tropical and subtropical waters around the world, in depths from 10-1,000 meters, but, while the group is moderately diverse at a dozen described (and undescribed) species, nowhere do we find more than two members of this genus in any given location. The recent review of Tea 2016 examined the species-level diversity in considerable detail, and the reader if referred there for a more detailed discussion. In that study, a hypothesized phylogeny was proposed that argued for an unusual evolutionary split for the genus, with separate Pacific Ocean and Atlantic Ocean clades.

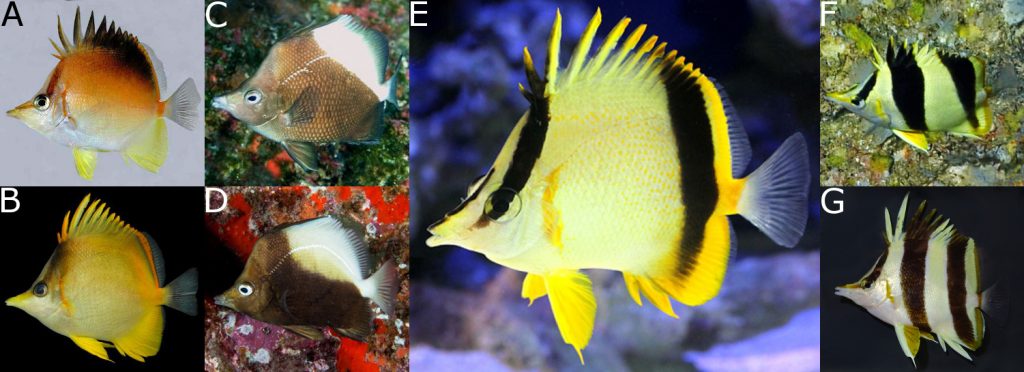

The vertical-banded group: A) P. aculeatus, B) P. brasiliensis, C) P. obliquus, D) P. dichrous, E) P. marcellae, F) P. guezei, G) P. “basabei” Credit: Van Tassel & Robertson, R.M. Macieira, Andre Seale, Luiz Rocha, uchiocomi, Peter Timm, Josh Copus

I’d like to instead propose a very different hypothesis, arguing that there are a pair of lineages which can be recognized by major differences to their color patterns. Of particular importance is whether the posterior black band is vertical or oblique, as this trait allows us to split this genus neatly into two mutually exclusive circumtropical groups (i.e. there are never two species with similar patterns found together). There are other subtleties that further support this distinction, such as the vertical yellow marking often seen along the pectoral fin base and the frequent presence of a submarginal orange band running from the rear of the dorsal fin, through the caudal peduncle, and ending in the anal fin. Both of these traits occurs in those species with vertical bands and are absent in those with oblique markings.

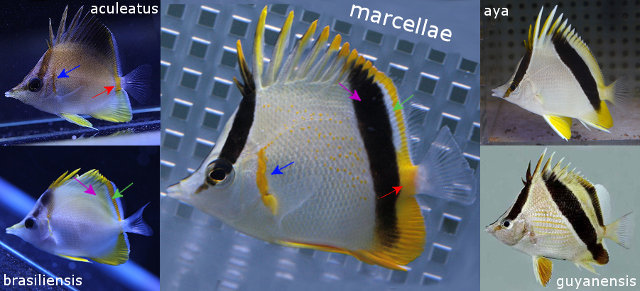

Comparing the West African P. marcellae to the West Atlantic taxa. Note the yellow pectoral stripe (BLUE), the yellow caudal peduncle stripe (RED), posterior vertical marking (PURPLE), and clear “window” in the dorsal fin (GREEN). Credit: Aqua Gallery Russo, uchiocomi, aquarise, Van Tassell & Robertson

These latter traits are important for placing those species which have secondarily lost the posterior black bar: P. aculeatus, P. brasiliensis, P. dichrous & P. obliquus. All four occur in the Western and Central Atlantic and appear most closely related to the Western African endemic P. marcellae. We can see the best evidence for this when examining the pattern of P. brasiliensis, which often shows traces of the vertical posterior band seen in its African sibling, as well as that species’ distinctive orange band in the dorsal fin/caudal peduncle and the orange vertical line along the pectoral fin base. On the other hand, Tea 2016 argued for a close relationship for P. marcellae and the oblique-banded Atlantic species P. aya and P. guyanensis, neither of which share these traits.

The oblique-lined group: A) P. aya, B) P. guyanensis, C) P. guyotensis, D) P. falcifer, E) P. carlhubbsi Credit: aquarise, Van Tassel & Robertson, Ross Robertson, Roger Steene

It’s interesting to note how the ecological preferences of this group seem to shift based on which ocean we look at. In the Atlantic, species like P. aculeatus and P. marcellae can be found in water as shallow as 10 meters or less, whereas their apparent closest relatives in the Pacific are normally only encountered well into the mesophotic zone at depths greater than 80 meters. Those species belonging to the oblique-banded clade show the opposite pattern—the Caribbean species (P. aya & P. guyanensis) typically occur only in deeper reefs, while the Eastern Pacific taxa (P. falcifer & P. carlhubbsi) can range more widely, from the shallows to well over 100 meters deep. The obscure P. guyotensis occurs deeper still, bottoming out at depths of around 300 meters, which helps to explain why this fish has been so seldom seen in the wild. The likely explanation for this is the relative lack of diversity and competition in the Atlantic and Eastern Pacific, which presumably drives the other Indo-Pacific members of this genus into less-competitive deepwater habitats.

There is still a great need for more detailed study of the Prognathodes butterflyfishes, particularly to determine if their genetic data supports the evolutionary relationships outlined here. The other major question left unanswered is which ocean this genus originated in—is this originally a Pacific group which colonized the Atlantic, or vice versa? And there are also three populations which probably need species recognition: the Hawaiian fish known in the trade as P. “basabei”, as well as the Pacific Ocean P. cf guezei and the Indian Ocean P. cf guyotensis. And who knows what else might be lurking out there… could there be a deepwater species yet to be discovered in West Africa or the Red Sea? It may yet be a while before we have definitive answers to these questions.

0 Comments