One of the most frequently encountered parasites of marine aquarium fishes is a mean-spirited flatworm known as the skin fluke. You can find this insidious invertebrate dining upon the skin and mucous of wrasses, angelfishes, butterflyfishes, rabbitfishes, triggerfishes and many other groups—as a rule of thumb, the more money you spend on an aquarium fish, the more likely it is to have skin flukes.

But, despite the ubiquity of this parasite at wholesalers and retailers, few aquarists make any real effort to keep it from entering into their aquariums, and, once introduced, there is often conflicting information on how best to eradicate it. Rather than parroting the same advice, let’s take a closer look at what the scientific literature has to say on the matter.

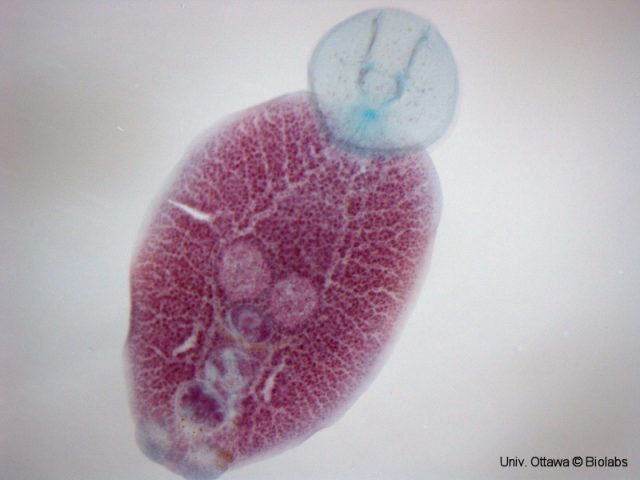

When we talk about skin flukes in the home aquarium, we’re really only talking about one species—Neobenedenia melleni (though the synonym N. girellae is often used interchangeably). It was originally discovered when specimens began infecting fish at the New York Aquarium in the 1920’s, and, since then, it has been found on over 100 different hosts species from over 30 families, mostly from the perciform and tetraodontiform orders, but also including a soldierfish, a catfish, a garden eel, a mosquitofish and several scorpionfish relatives.

With such a wide range of targets, this widespread parasite has unsurprisingly become a major economic problem in the commercial aquaculture of food fishes, with most relevant scientific research focused here rather than on its impact for aquarium hobbyists. On the other hand, the impact of this pest in the wild has seen little exploration. In one study of Caribbean surgeonfishes, anywhere from 10-100% of specimens showed the presence of Neobenedenia, with the highest rates coming from Blue Tang (A. coeruleus) collected in shallow bays. This is a remarkably prolific worm, capable of self-inseminating in the absence of a mate and able to lay upwards of 500 eggs a day and more than 3000 in the course of its three-week lifespan. Thus, a single fluke introduced into an aquarium can quickly and easily start a sizable population.

This is a remarkably prolific worm, capable of self-inseminating in the absence of a mate and able to lay upwards of 500 eggs a day and more than 3000 in the course of its three-week lifespan. Thus, a single fluke introduced into an aquarium can quickly and easily start a sizable population. Symptoms of infection include reduced feeding, lethargy, cloudy eyes, excessive mucus production and discolored or darkened skin.

Since this parasite is mostly transparent, it is effectively invisible on the host fish until closely examined, and, unlike some parasites which target a specific part of their host, Neobenedenia can be found nearly anywhere on a fish, including the fins, gills, eyes and even the nasal cavities. Often the first indication of an infestation can be seen in the characteristic “flashing” behavior of infected fish, which manifests as erratic swimming and scratching against any firm structures as the unluckyhost attempts to scratch these irritants off its body.

If left to multiply, this parasite can quickly reproduce to plague proportions and is able to easily kill aquarium specimens that are susceptible to its wormy wrath. As far as treatment goes, there are three methods which warrant discussion:

- Biological controls, such as cleaner fishes and shrimps

- Environmental controls, altering water parameters, such as temperature and salinity

- Chemical controls, adding medications and supplements.

Fortunately, there is a vast literature which has examined these variables in exquisite scientific detail, so, unlike so much aquarium hearsay, we can speak accurately as to what works and what doesn’t for eliminating Neobenedenia.

In part 2 of this discussion, we will explore these treatment methods in detail…

0 Comments