A Melanistic pair of Amphiprion milii from Darwin, Australia. Credit: Cameron Bee / Monsoon Aquatics

Monsoon Aquatics made waves recently with the discovery of a couple new species of Cirrhilabrus in the Timor Sea, and they’re at it again with the collection of one of the rarer anemonefishes in the aquarium trade, Amphiprion milii, from the waters near Darwin, Australia.

Note the dark dorsal fin margin, which separates this species from the similar, but distantly related, A. sebae of the Indian Ocean. Credit: Cameron Bee / Monsoon Aquatics

If you’re scratching your head right now, asking yourself, “What’s an Amphiprion milii?”, you’re not alone. Since the last major review of the genus by Gerry Allen, this name has been treated as a synonym for Clark’s Anemonefish (A. clarkii), but, as I’ve discussed elsewhere, there is not one species of A. clarkii, but many… perhaps as many as 16, each endemic to a small corner of the Indo-Pacific and each displaying recognizable traits that allow us to tell them apart. For more on this, see my discussion of A. snyderi from the Ogasawara Islands, the Barrier Reef Anemonefish, and the Chagos Clark’s Anemonefish.

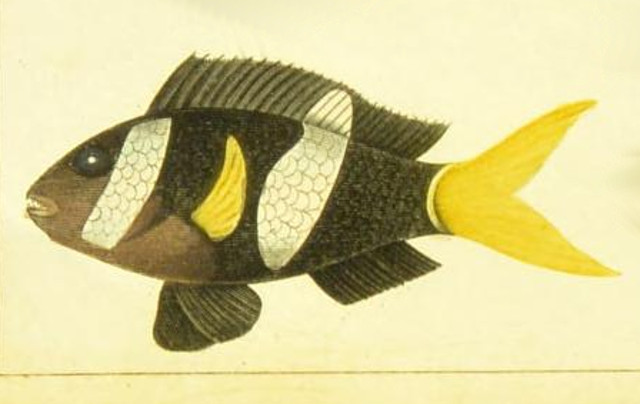

Amphiprion milii holotype illustration. From Bory de Saint-Vincent, 1831. Dictionnaire Classique d’Histoire Naturelle. v. 17, Plate 113, fig. 2

The name A. milii originates from an 1831 description by French naturalist Jean Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent and honors French naval officer Pierre Bernard Milius, a lieutenant aboard the famed Baudin expedition which first mapped large parts of Australia in the early 19th century. Some 2,500 new species were described on this voyage, with A. milii discovered at Shark Bay, Western Australia. Unfortunately, while we do have a type locality, there is no known type specimen, but the illustration which accompanies its description clearly aligns with the fish shown above. In both of these, the body is black throughout, with a bright yellow caudal fin and two stripes, the middle of which is rather wide and asymmetrically bulged.

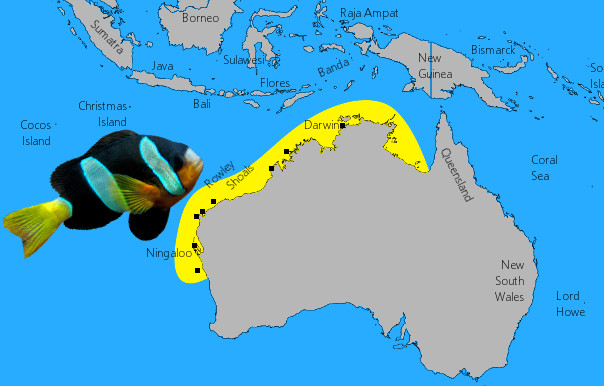

Records of this fish are primarily from a small portion of Australia’s western coastline, stretching from the reefs of Houtman Abrolhos, Shark Bay and Exmouth in the south, up to Ningaloo and the Dampier Archipelago. North of here, coral reefs become less common, but scattered reports of this fish exist from Coulomb Point Nature Reserve and Montgomery Reef off the Kimberley Coast. Records from Darwin, Australia have been known as well, but, until now, it hasn’t been clear if this was the same species or, instead, a southerly contingent of the Indonesian A. cf clarkii or an entirely different fish altogether..

A couple key traits allow us to tell these two apart: 1) the solid yellow coloration of the caudal fin, which, in Indonesia, is noticeably whiter in females, with males having yellow only on the upper and lower margins of the tail. 2) the unusually thickened and asymmetrical shape of the middle stripe, which gives this Aussie anemonefish a sort of faux-latezonatus appeal.

Non-melanistic phenotype of A. milli seen at Coral Bay with another endemic species, Amphiprion rubrocinctus. Credit: Geoffrey Zuccolo

One of the most unique and diagnostic characteristics to look for is a brown color spread throughout the spinous dorsal fin and upper back. Other nearby populations, such as those from Indonesia, the Rowley Shoals and the Eastern Indian Ocean, have this area black in mature individuals. Unfortunately, the specimens acquired by Monsoon Aquatics lack this identifying feature, indicating that these were likely found in either a Stichodactyla or Cryptodendrum anemone. These hosts are known to produce melanism in the clarkii species group, which is perhaps the biggest reason why these fishes have been mired in so much confusion—melanism obscures many of the most useful traits needed for identification.

This is by no means the first time this fish has been collected for the aquarium trade. These have been a sporadic offering for quite some time, referred to as the “Australian Black Clark’s Clownfish”. They’ve even been available from major breeders like Sustainable Aquatics. You’ll also sometimes see other species from this group misidentified as this Western Australian endemic. These are usually either melanistic specimens of the true A. clarkii from the Maldives—these have a narrower middle stripe—or melanistic A. papuensis (=clarkii) from Melanesia, which have a distinctive yellow tip to the soft dorsal fin in melanistic forms.

Even the non-melanistic phenotype is considerably darker than most other species in the clarkii group. From Exmouth. Credit: Royle Safaris

Among the many species in this diverse anemonefish lineage, Amphiprion milii stands out more than most thanks to its unusually distinctive appearance. It’s not entirely clear which species/population it might be most closely related to. Perhaps it’s the similarly yellow-tailed fish found in the Eastern Indian Ocean… or maybe its the A. cf clarkii found in the Barrier Reef—there are other examples of Australian taxa (e.g. Chaetodontoplus personifer & C. meredithi) split by the Torres Strait. Or maybe A. milii is a more distant relative than its appearance would lead us to believe? This is where the limitations of our understanding become obvious and where genetic study would most benefit.

Also unknown is the overall health of this fish’s population. As an example, the Houtman Abrolhos Islands once contained a vast 185 X 400 meter aggregation of anemones (known, appropriately enough, as the “Anemone Lump”) said to house hundreds of A. milii. But, as reported in Thomas et al 2014, these anemones disappeared for unknown reasons, and, along with them, so vanished their attendant anemonefish. As this localized population decline hopefully illustrates, the issue of where we should draw the lines when recognizing species is not a purely pedantic point to be argued about by some small cadre of taxonomists. For this fish, which clearly has a separate evolutionary history from others in its group, there are legitimate concerns about its health in the wild. But when it is erroneously treated as identical to the other Clark’s Anemonefishes of the Indo-Pacific, it becomes impossible to properly discuss the perils it may face. By failing to identify its status as a unique species, we fundamentally limit our ability to study and protect it.

- de Saint-Vincent, B., 1831. Dictionnaire classique d’histoire naturelle (Vol. 17). Rey et Gravier.

- Thomas, L., Stat, M., Kendrick, G.A. and Hobbs, J.P.A., 2014. Severe loss of anemones and anemonefishes from a premier tourist attraction at the Houtman Abrolhos Islands, Western Australia. Marine Biodiversity, 45, pp.143-144.

0 Comments