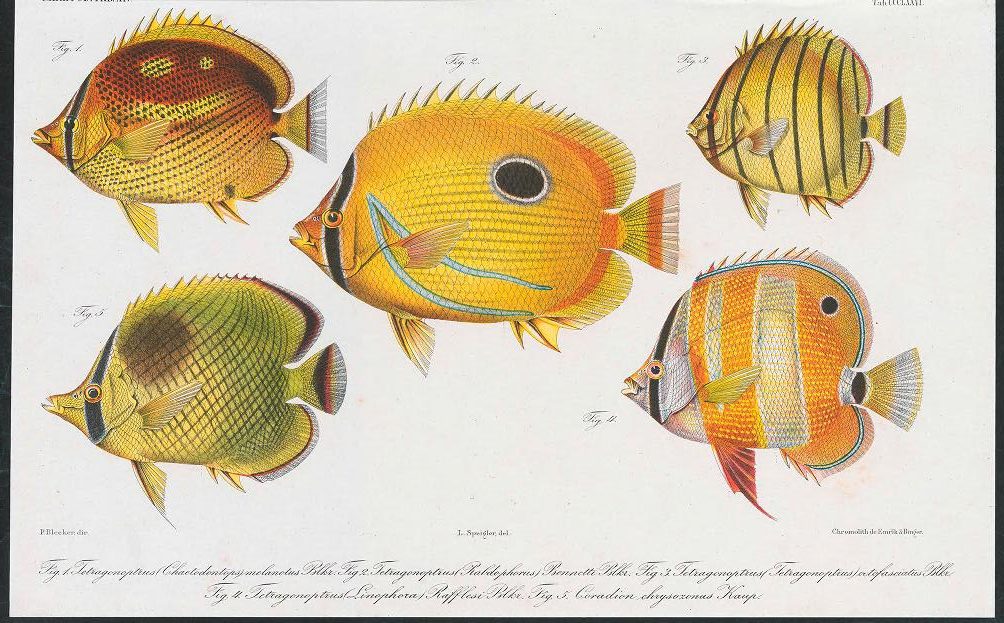

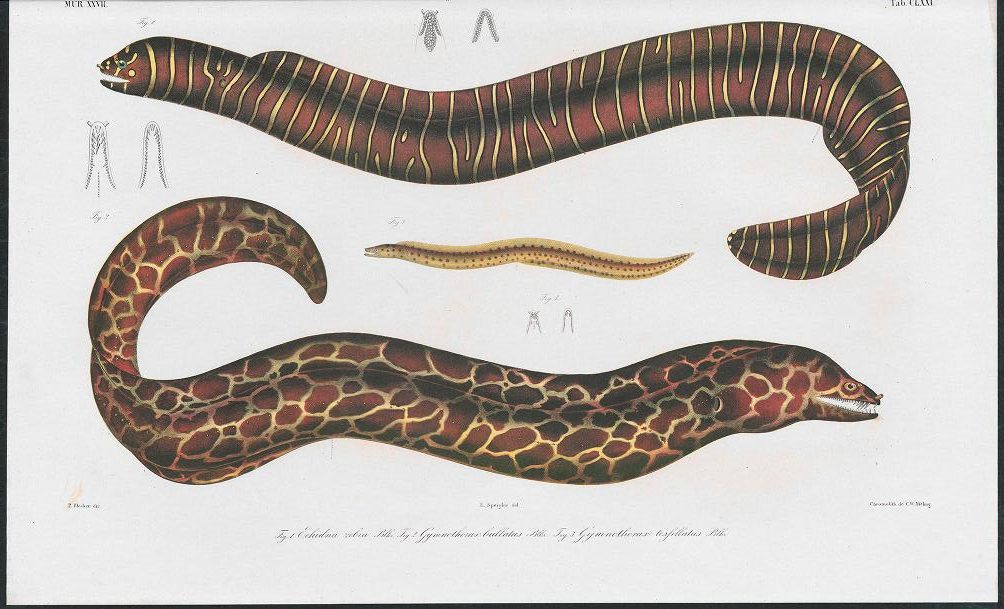

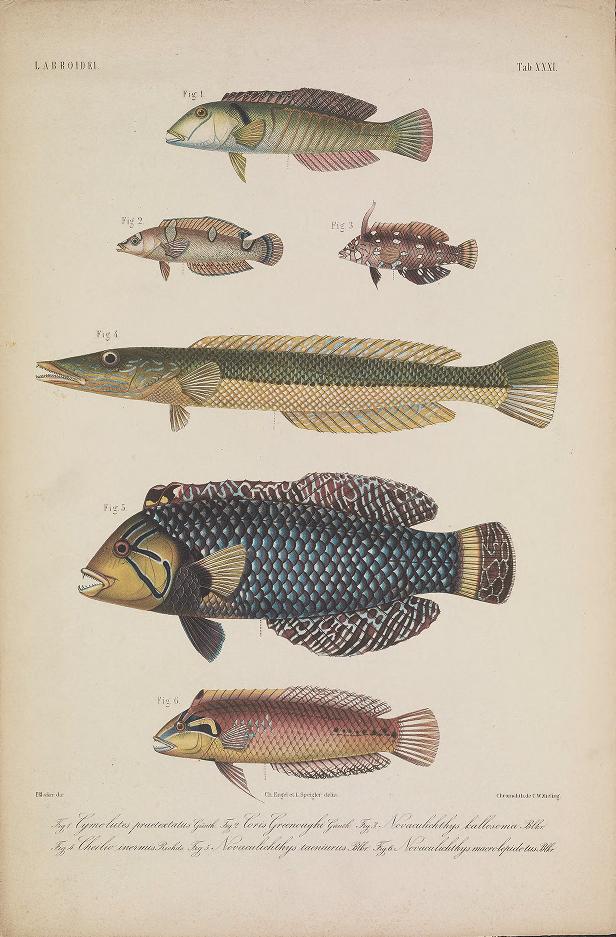

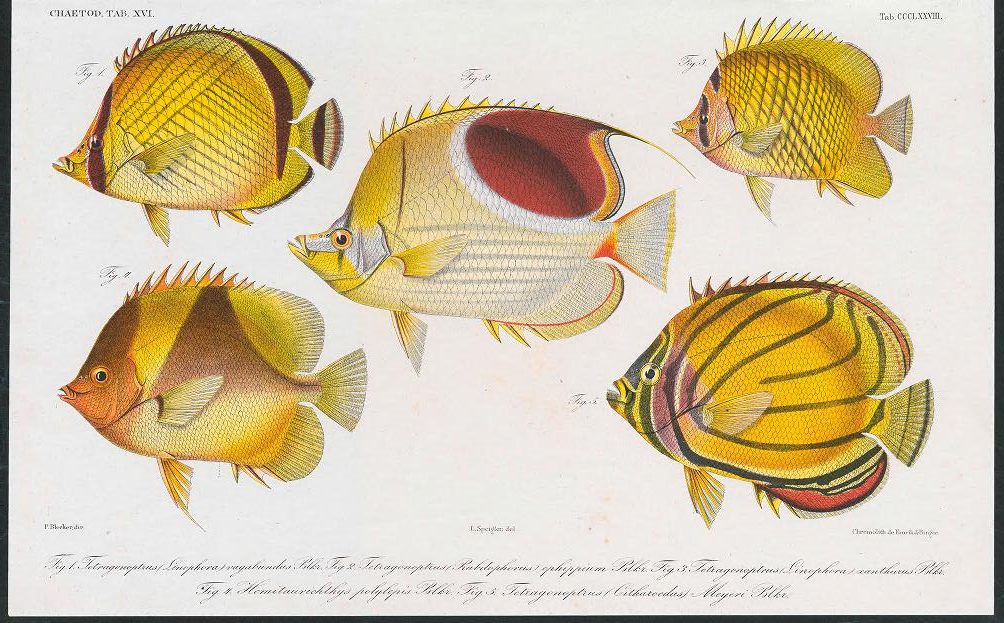

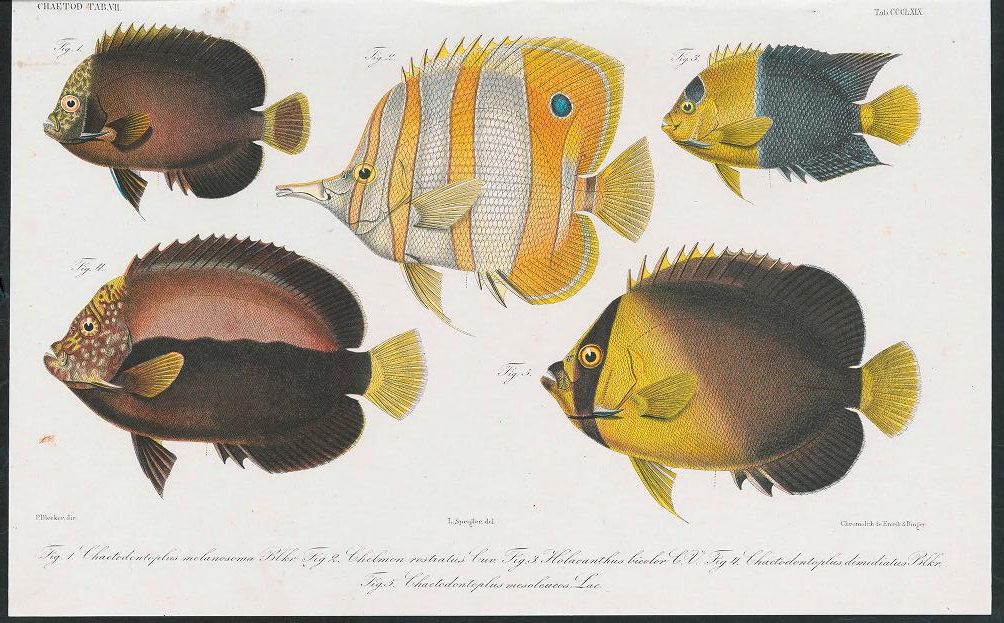

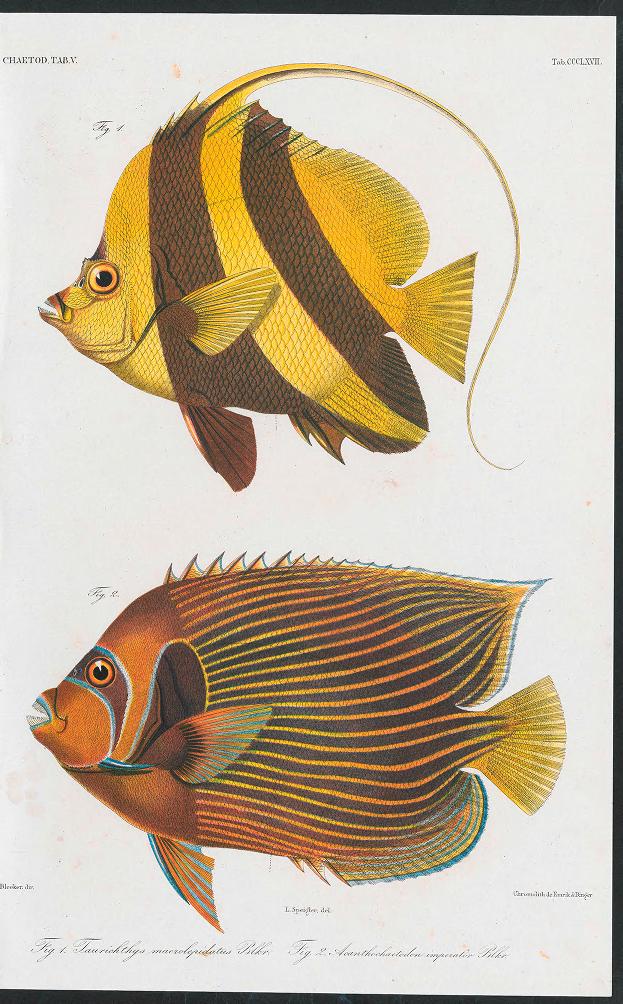

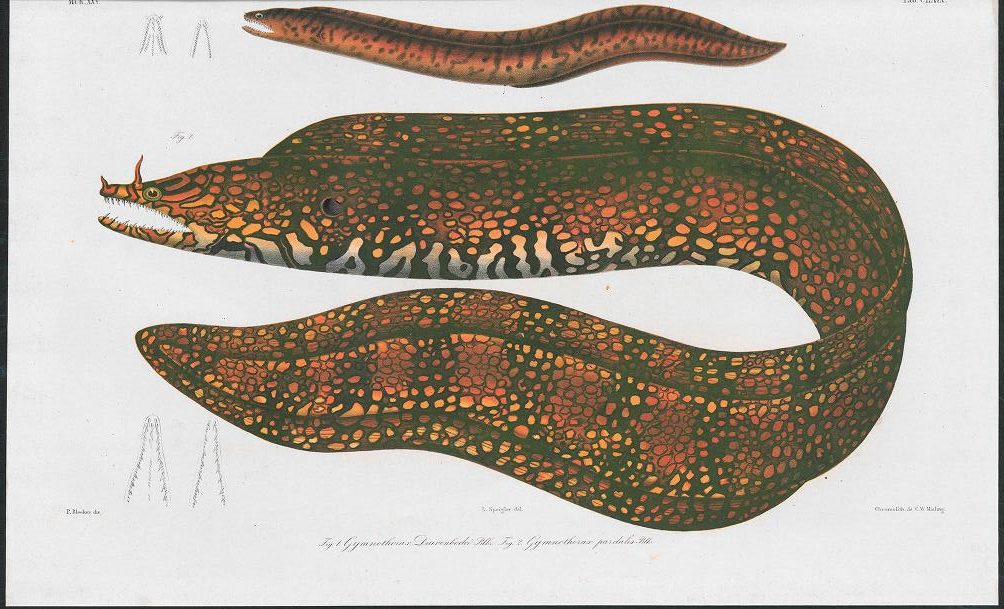

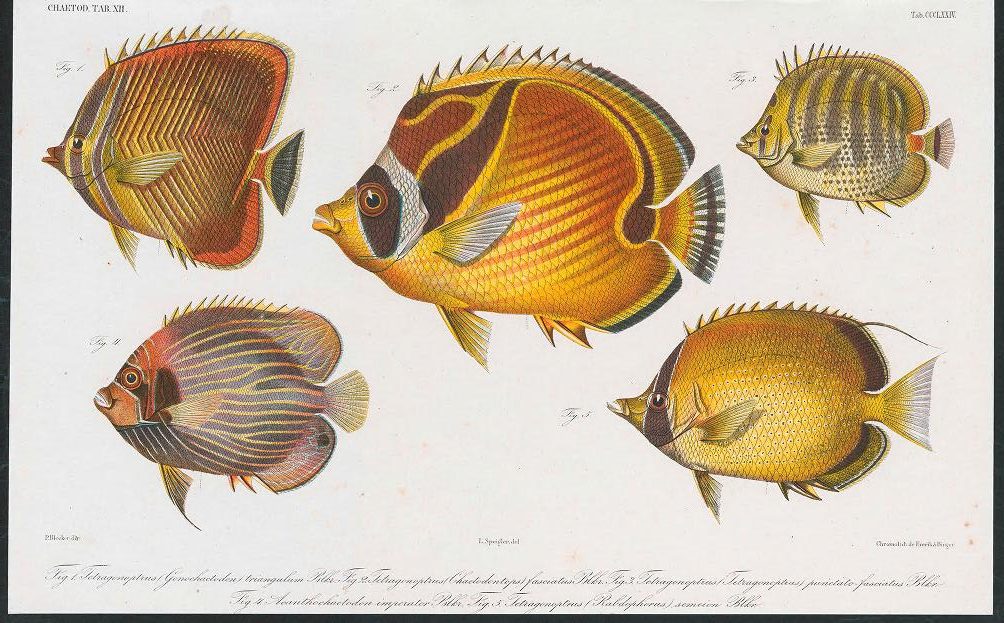

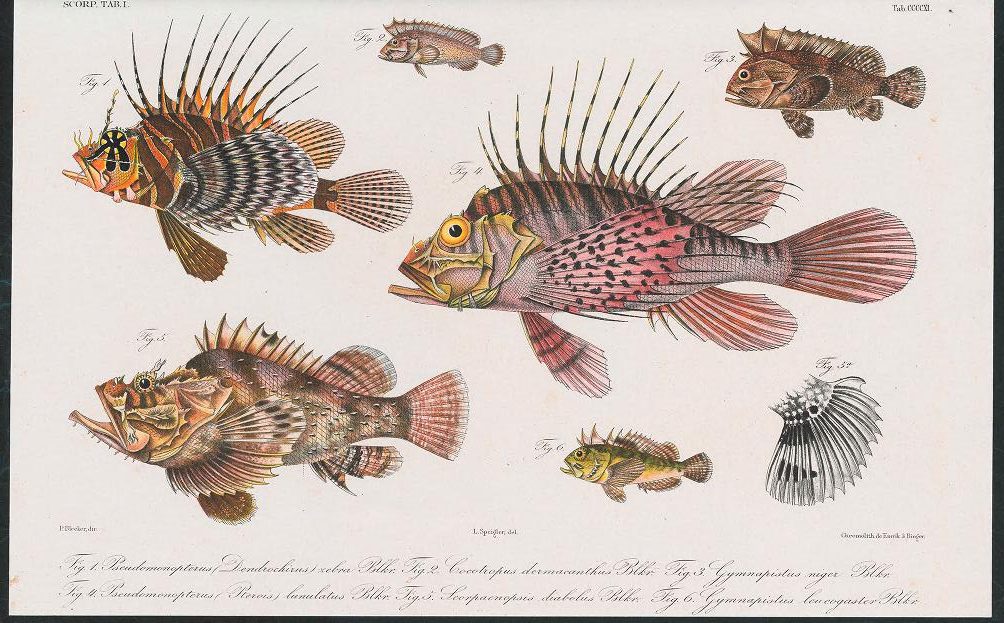

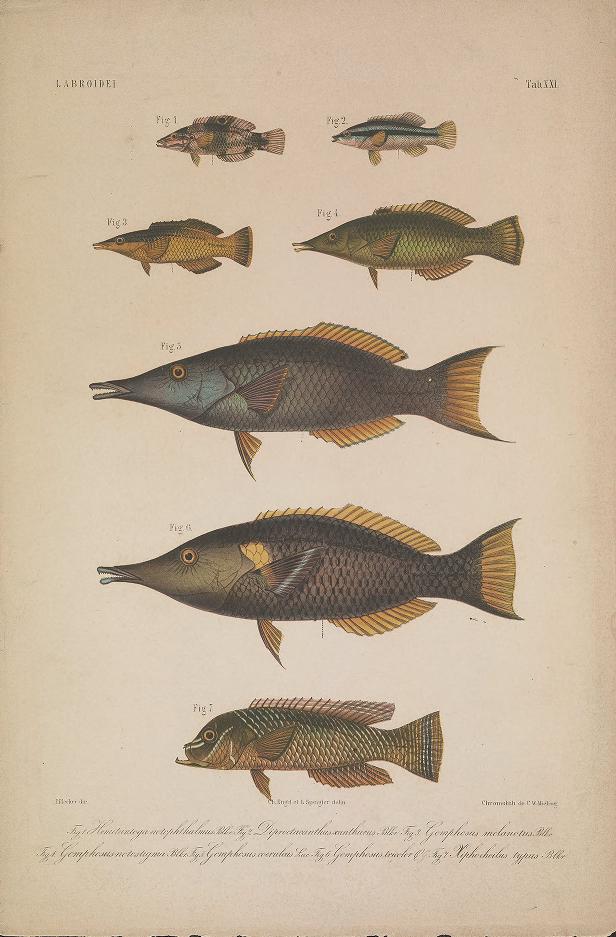

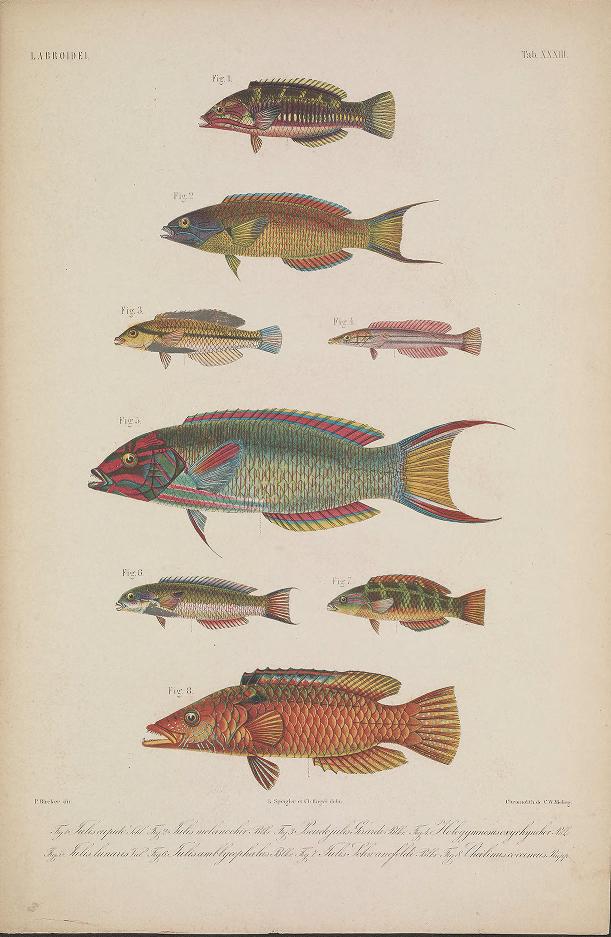

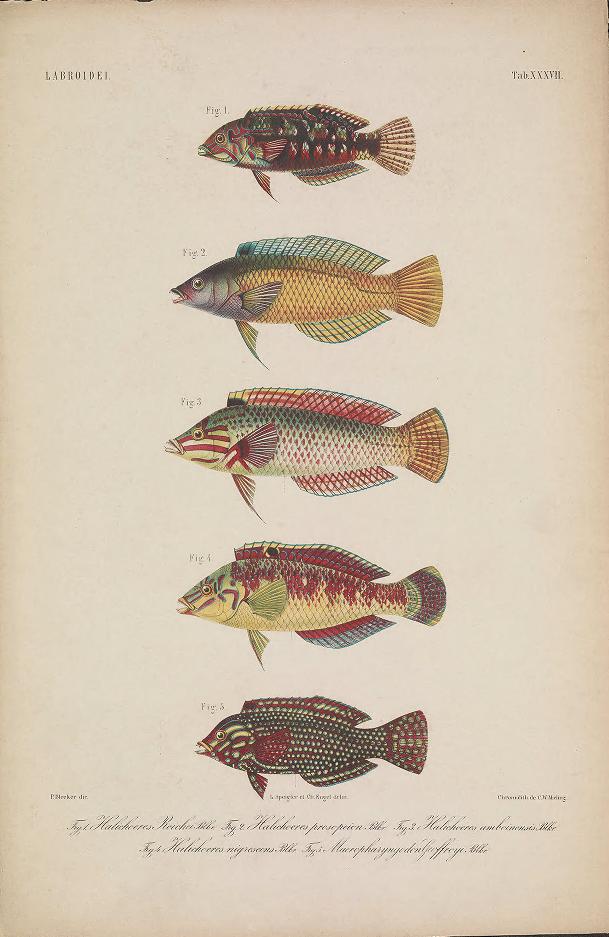

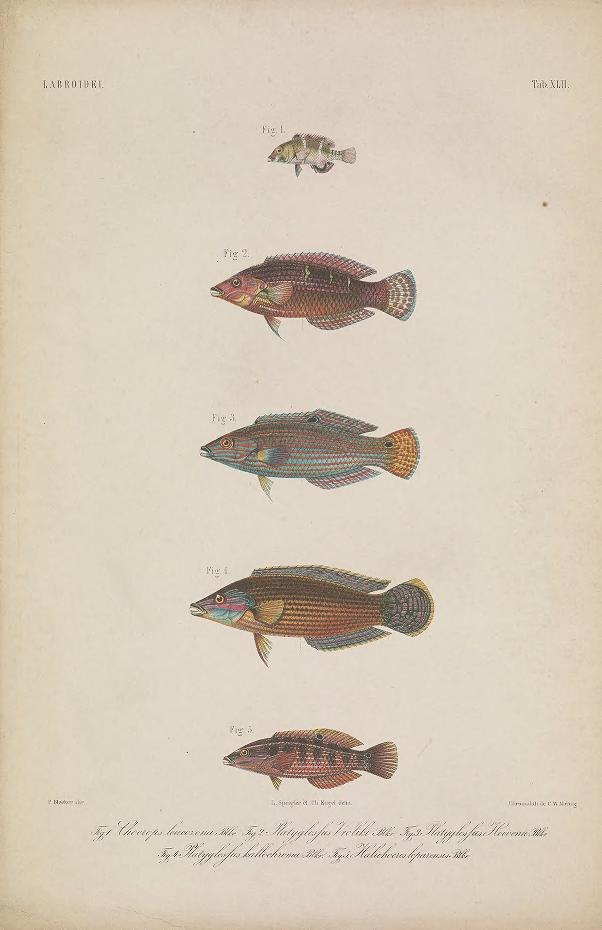

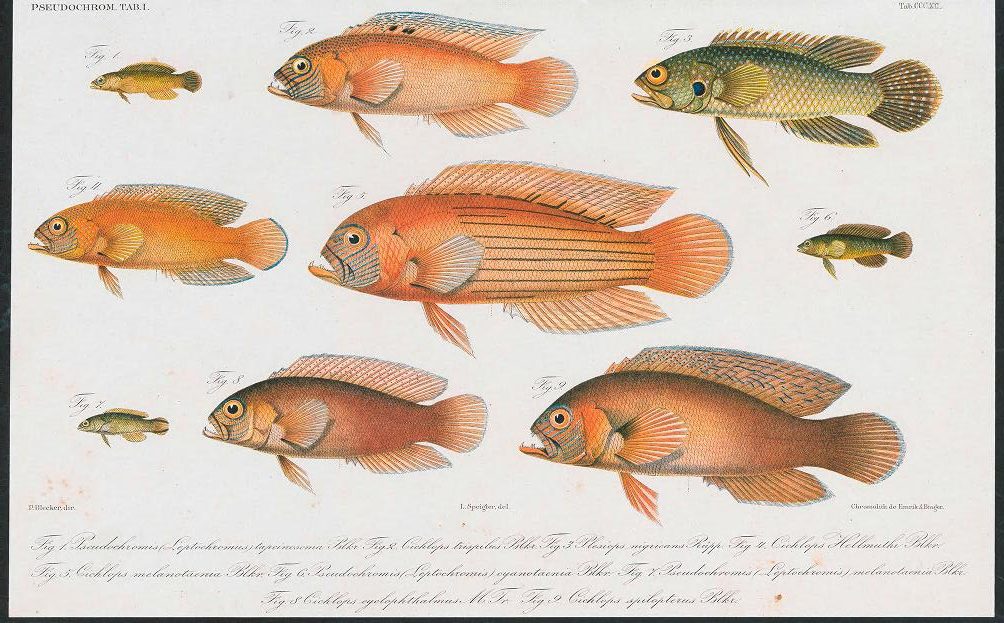

The 19th century was a golden age for marine exploration and ichthyological discovery, and a majority of the coral reef fishes familiar to us today were first described during these formative years. To fully convey to a curious public the vibrant colors and ornate patterning of these new species, researchers included lavish illustrations alongside their written descriptions. Centuries later, these works stand as some of the finest pieces of natural history art ever created.

Among the most important ichthyologists from this period was a little-known Dutch medical officer, Pieter Bleeker, who had no formal training in zoology. For nearly two decades, while stationed in the mostly unexplored islands of Indonesia, Bleeker collected and described new species of freshwater and marine fishes at an extraordinary rate. By the time he returned home to the Netherlands, he had discovered more than 500 new genera and well over 3,000 new species!

Bleeker’s earliest works were mostly limited to individual descriptions, but, as his hobby turned into a driving passion, he became a true expert in the field, authoring some of the most important ichthyological treatises from this era and establishing much of our current classification for reef fishes. His crowning achievement is his Atlas Ichthyologique des Indes Orientales Néerlandaises (Atlas of Fishes of the Dutch East Indies). This gargantuan tome, published in 36 volumes from 1862–1878, would occupy the remaining years of his life, and, sadly, he would not live to see its completion.

The Atlas was by far the most complete study of coral reef fishes in its day; however, since it was published primarily in Danish, it has in many ways been forgotten. Today, it’s unlikely that anyone outside the taxonomic community will be familiar with Bleeker’s magnum opus, even though it contains some of the most incredible ichthyological illustrations ever produced. The artists, Ludwig Speigler and Chris Engel, created dozens of color plates, depicting hundreds of species that were, whenever possible, drawn to lifelike proportions.

It’s truly remarkable how accurate these drawings are when one considers that the artists had never seen their subjects alive. By the 19th century, natural history illustration had matured considerably. Gone were the distorted shapes and whimsical flourishes that plagued the earlier efforts of Samuel Fallours and Marcus Elieser Bloch. Though it’s been a century and a half since it’s publication, time has done little to age Bleeker’s achievement. As a work of science and art, his Atlas stands alone in terms of both its lasting scientific importance and the sheer beauty of its illuminations.

0 Comments