Staghorn corals killed by coral bleaching on Bourke Reef, on theNorthern Great Barrier Reef, November 2016.

Credit: Greg Torda, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies.

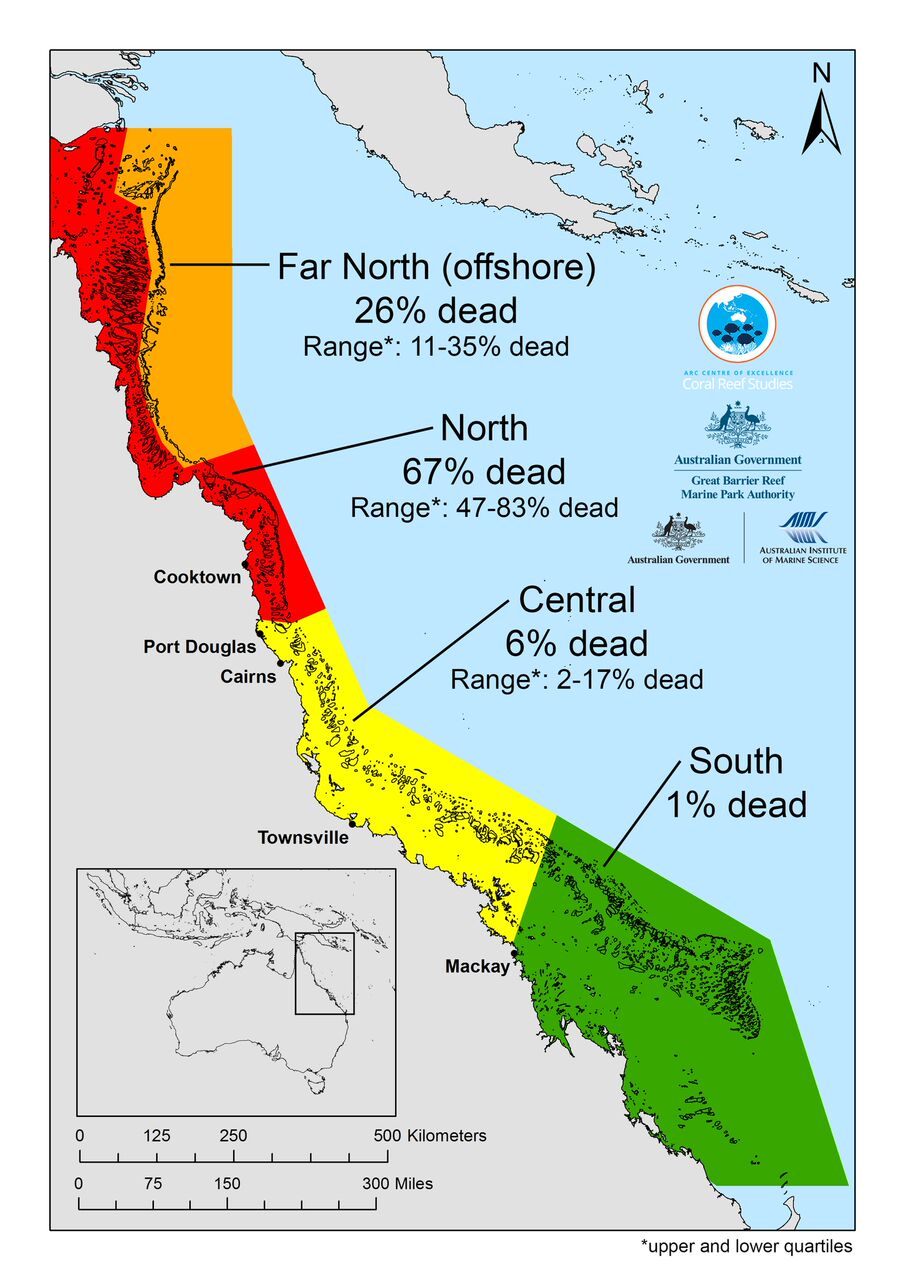

The damage has been severe, but regional. Most of the die-off occurred in the northern region, with little damage occurring to the south, though another event could cause more problems and slow recovery, warn the team.

In a media release, Professor Terry Hughes, Director of the Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies based at James Cook University, who undertook extensive aerial surveys at the height of the bleaching said:

“Most of the losses in 2016 have occurred in the northern, most-pristine part of the Great Barrier Reef. This region escaped with minor damage in two earlier bleaching events in 1998 and 2002, but this time around it has been badly affected.”

“The good news is the southern two-thirds of the Reef has escaped with minor damage. On average, 6% of bleached corals died in the central region in 2016, and only 1% in the south. The corals have now regained their vibrant colour, and these reefs are in good condition,” says Professor Andrew Baird, also from the ARC Centre, who led teams of divers to re-survey the reefs in October and November.

The map, detailing coral loss on Great Barrier Reef, shows how mortality varies enormously from north to south

Credit: ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies

The researchers were keen to emphasize the benefit the reef’s survival and health has for the region’s tourism industry, which employs 70,000 people, and generates AU$5 billion in income each year.

Healthy Coral in the Capricorn Group of Islands, Southern Great Barrier Reef, November 2016.

Credit: Tory Chase, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies.

Also in the statement was evidence of local survival of corals:

“We found a large corridor of reefs that escaped the most severe damage along the eastern edge of the continental shelf in the far north of the Great Barrier Reef,” says Professor Hughes.

“We suspect these reefs are partially protected from heat stress by upwelling of cooler water from the Coral Sea.”

The statement goes on to say that the northern region will take at least 10-15 years to regain the lost corals, though the scientists are concerned another bleaching event could hamper recovery.

Jose Luis Mora