The Blue Blubber jelly (Catostylus mosaicus) is a member of the Catostylus genus; a genus which contains 12 other species of jellyfish. It shares the phylum of Cnidaria with 10,000 other species including corals and anemones. Blue Blubbers are found in the coastal regions of the Indo-Pacific. It is one of the most prevalent jellies found along the eastern coast of Australia. Populations used to be kept in check by predators such as tuna or sea turtles, but due to the decline of these predators from overfishing and pollution, the blue blubbers have had a big bloom. Because of its abundance this jelly is fairly easy to obtain in captivity. Usually it needs to be special ordered from your retailer or wholesaler, mainly due to inability to keep jellies long term and their short lifespans.

Grey Variation of the “Blue” Blubber Jelly (Catostylus mosaicus) Photo by Noel Heinsohn

The blue blubbers can sometimes be found in estuarine waters. This means that they can

tolerate a wide range of salinities. I have found that 32-35 parts per thousand work the best for our specimens.

These blue jellies come in a variety of colors ranging from light blue to dark purple to even

burgundy. Its bell pulses very distinctively, in a staccato-like rhythm. They are fairly quick moving for a jelly species, and propel themselves through the water, unlike many other species of jellies that drift along with the current. This is a key benefit in keeping C. mosaicus, because that means you do not necessarily need to have to keep them in a kreisel. When I had C. mosaicus at the Long Island Aquarium, they were kept in a modified 40 breeder. There was a spray bar to keep them off the overflows, and a black piece of sintra cut to fit the tank to really make their colors pop.

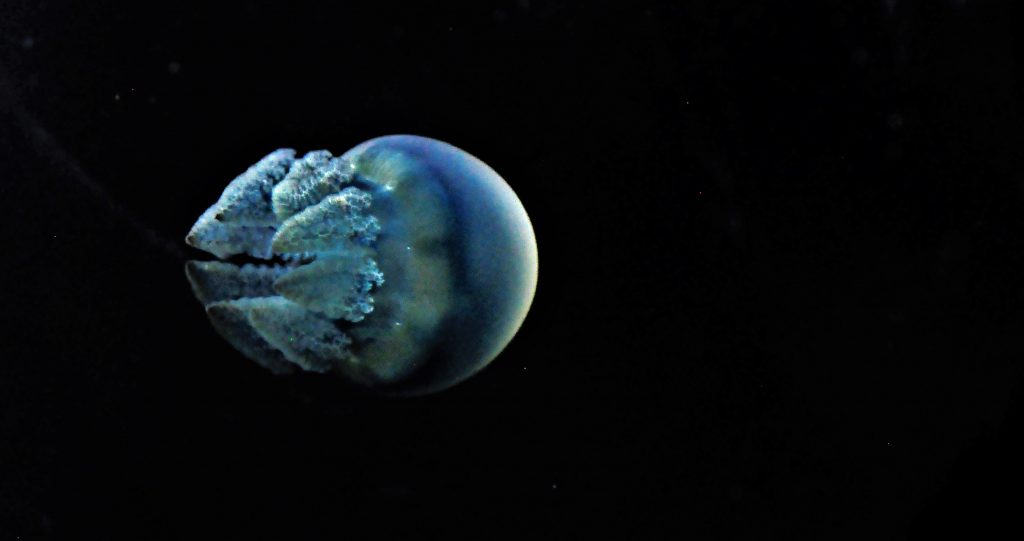

Variation of the “Blue” Blubber Jelly (Catostylus mosaicus) Photo by Noel Heinsohn

Besides their unusual coloration, blue blubbers are unique in a few other ways. They lack tentacles, and instead have eight clublike oral arms that each contains several mouths. These mouths are used to transport food to their stomachs which are located within their bell. This species only has one stomach, but some jellies may have up to ten! Their diet consists of a variety of zooplankton in the ocean. This is due to the size of its minuscule mouths. Here at the aquarium, I would feed a mix of enriched brine shrimp, copepods, and rotifers to ensure they obtain enough nutrition. It is important to feed these jellies as often as possible. During my day I would usually stop by once an hour to drop some live food in. I would recommend feeding a minimum of 4 times a day. It is vital to not only offer a variety of foods but also enriched prey items. Offering the zooplankton some algae a few minutes prior to feeding will ensure they are gut loaded and ready to go! Both Algagen and Reef Nutrition offer a multitude of great planktons you can feed out to your jellies.

A Blue Blubber Jelly (Catostylus mosaicus) Photo by Noel Heinsohn

Along these oral arms is an arsenal of nematocysts. Nematocysts are specialized cells that contain a coiled venomous thread that can be launched at both predators and prey alike. These nematocysts are activated by the stimulation of an outside source. When these nematocysts are put into action on prey they are very effective for killing or paralyzing; thus making it a much simpler task for the blubber to consume its prey. This same technique is used to attempt to ward off predators. Unfortunately for the blubbers this tactic is not always effective, especially when up against a mega-predator(Mega to the Jellies) like a sea turtle. Now these nematocysts may effect humans, but for most the blue blubber only causes a minor irritation of the skin. But there is a chance of having an allergic reaction.

Like its relatives the Cassiopea jelly, C. mosaicus has a symbiotic relationship with unicellular algae. Like most symbiotic algaes (and most algaes in general) they are photosynthetic. So they use the sun to produce energy for both themselves and their host the blue blubber jelly. This means that a part of the blubber diet comes from this photosynthesizing algae. The percentage of nutrition derived from the algae is actually quite small. So this being said I do not think that it is necessary for the blue blubber to have a strong light. In my experience with this species they thrive in a tank that is being well fed. If you are giving them lots of food ,they will have the energy needed for life processes. In the ocean, when the sun goes down, so does the C. mosaicus. It descends to lower depths to feed on other microscopic organisms that it encounters. Between the symbiotic algae, and the zooplankton these species have a well-rounded diet that gives them plenty of nourishment.

A Blue Blubber Jelly (Catostylus mosaicus) Photo by Noel Heinsohn

Despite their increase in population, the blue blubber jelly is very difficult to culture in captivity. It has been successfully cultured before, but not in vast numbers. This is a species that I think could use a lot more attention for culturing.

Maroon Variation of the “Blue” Blubber Jelly (Catostylus mosaicus) Photo by Noel Heinsohn

In closing I think that the blue blubber jelly is a beautiful species. They captivated guests here at the aquarium, myself included. They were a spectacularly interesting species to work with. This being said I no longer keep them here at the aquarium due to their short lifespans, and the difficulties in culturing them. So, would I recommend them to every hobbyist? No. I think there are a lot of very neat jelly species that have a longer lifespan in captivity and are a lot easier/hardier to maintain that should be attempted first. I would say these are a species that should be left to more experienced jelly keepers. Home jelly tanks are becoming increasingly more and more popular. With the advances being made on these “jellyquariums” it won’t be too difficult for everyone to get their hands wet with more exotic species like C. mosaicus soon. If you are interested in keeping jellies I would recommend starting with a moon jelly species and working your way up. It is my hope that one day more and more people will get excited about keeping jellies, and I will see more hobbyists with the capabilities to care for them.

Variation of the Blue Blubber Jelly (Catostylus mosaicus) Photo by Noel Heinsohn

Thanks again to Tyler Mourey for coauthoring this series with me!

0 Comments