A young tripletail, Lobotes surinamensis. This is a regulated species in most southern states.

It’s easy to forget, when you’re out on the water with nets, buckets and aerators that the laws regulating the take of food and game fish apply to you just as they apply to an angler with a rod and reel. While it’s true that in most states, excluding Florida and Hawaii where marine ornamentals constitute a commercial industry, enforcement agents are likely to overlook someone with a dip net and bucket, because in most cases, someone with that gear is probably just looking for bait. It’s also likely that if you’re out in search of aquarium fishes, you probably don’t have any interest in the average food or game fish. Nevertheless, at times these fishes may find their way into our buckets and the temptation to take them home to your aquarium can be great.

This juvenile spanish mackerel is a sleek looking fish, but it would never survive the trip home and it is clearly not legal size.

Failing to recognize that this is a young mahi mahi, Coryphaena hippurus is a forgivable offense as few people have a had a good look at one in this juvenile coloration, but it’s about as far as you can get from a suitable aquarium species.

There are two common reasons for this legal faux pas. The first is that, as you stand there looking into your net it occurs to you that a juvenile flounder (or seabass, or snapper) might make a unique addition to your tank, at least for a while. However, I believe that more often it’s a case of misidentification (or absence of identification). In fact, the inspiration for this article came from a fish identification group on Facebook. I noticed that some members were posting photos of fishes that they had already brought home from a collecting trip, then asking for help identifying those fish. Now there are a number of issues that need to be addressed here, but let me start with husbandry. This is the wild-collector’s equivalent of making an impulse buy at the fish store. You might even say that it’s worse. Any responsible hobbyist knows the dangers of taking a fish home before thoroughly researching details like maximum size, life span, and requirements for care. But at least when it happens at the LFS, you usually know what species you’re dealing with, so you can google it on the way home and perhaps find out what a terrible decision you’ve made before your new pet is finished acclimating. You also have a pretty high degree of confidence that if any laws were broken along the supply chain for that fish, you probably won’t be held accountable. Not so when you are the entire supply chain.

It’s easy to get excited when you spot this deep-bodied, laterally compressed fish among the mundane minnows in your net, but this is a baby permit, Trachinotus falcatus. It will grow to over a meter long and can weigh up to 36kg. It is also regulated as a game fish in many states.

If you decide you want a flounder in your tank, there’s no need to risk a fine. Although some flounder species are regulated, most are not. This windowpane flounder is one of at least six species that occurs in North Carolina. Only the southern flounder is regulated here.

Taking an unknown species home from the wild means, minimally, that you have no idea what it eats, how big it will grow, how much space it needs, what kind of tolerance it has for the water parameters in your tank, whether it poses any health or safety risks to you, and of course, whether you are legally permitted to possess it. I’m not saying that it’s never acceptable to keep an unidentified fish, especially if you have ample quarantine and holding space, and a plan-B in case it doesn’t work out. Assuming you are well prepared for whatever your mystery fish grows into, it is important to, at very least, be certain that you aren’t breaking any conservation laws. This can be tricky, particularly in temperate regions where there is a wide variety of native, migratory, and transient species with local and federal laws governing their collection. Having a solid handle on applicable laws, relevant boundaries, and species ranges can save you a lot of headaches. >))))>

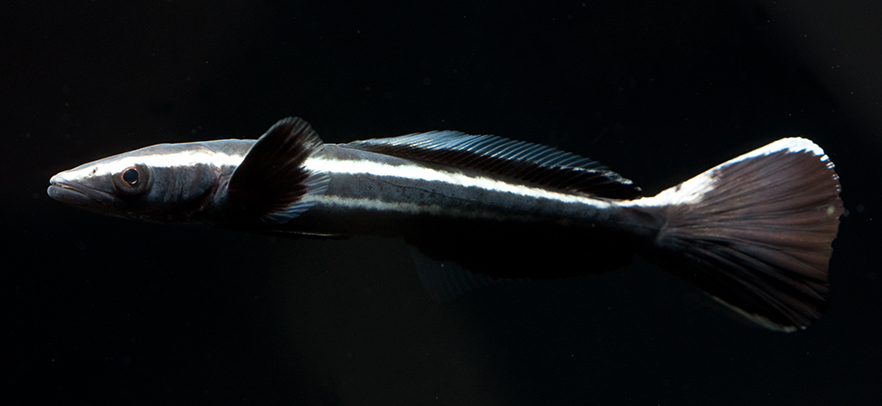

Collectors often mistake young cobia for remoras. That’s no excuse to take one home as both species are extremely problematic, even in public aquaria, not to mention, cobia can grow to two meters in length!

0 Comments