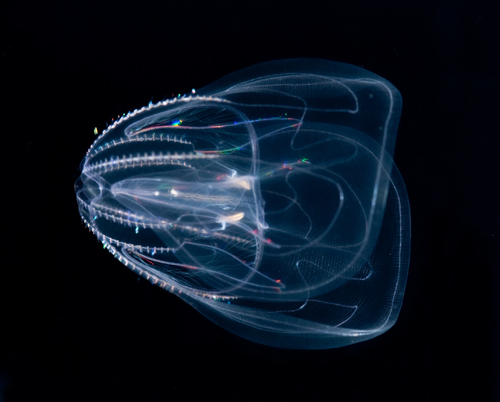

Comb jelly, Mnemiopsis sp.

Last year, as I was attempting to design my dream larval culture system while staying within the space limitations of my small laboratory/classroom, I had the brilliant idea to use pseudo-kreisels as rearing tanks. Kreisel and pseudo-kreisel tanks are typically used for housing jellyfish and other delicate, pelagic animals, so I was hopeful that they would alleviate some of the problems associated with keeping pelagic fish larvae in a confined space. Unfortunately for my rearing efforts, they were an epic failure. Most of the larvae oriented themselves, facing into the current, but not in the horizontal sections as I had planned. This caused them to either be swimming into the bottom of the tank, or up toward the water’s surface. They also nosed into, and became trapped in the corner seams along the front and back of the tank, and never survived more than a few weeks. After several failed attempts, I decided to abandon them as larval rearing vessels, at least for the time being. I left the tanks running however, because I thought it might be nice to have some jellies on display when we study phylum cnidaria in my marine biology class. I made a mental note to keep an eye out for interesting jellyfish on my beach excursions, but somehow, between trying to keep my four-year-old son safe in the water, and the constant distraction of actual fish, I never got around to it. Then, one afternoon while shining my flashlight into various buckets of rotifers and copepods in my lab (that’s how I check their density), I came across a bucket I hadn’t looked at in weeks. It was a bucket that had contained some leftover wild plankton from a lab activity in my marine bio class more than a month earlier. It hadn’t been aerated or fed in all of that time, but something had survived. There were dozens of tiny comb jellies lazily swimming around the bucket with their long, branched juvenile tentacles fully extended. They must have come in as larvae because none of my students reported seeing any comb jellies in their microscopic examination on this sample. I pipetted them out of the bucket, one at a time, and placed them into one of the pseudo-kreisel tanks. I also found and kept a couple of very small medusae in the bucket and placed them in the tank with the ctenophores, knowing that they might cause me some headaches down the road. At the end of each day, I fed them the day’s leftover foods from the latest larval project, which usually consisted primarily of copepods from Algagen. They continue to grow and they have become the favorite display in my classroom. It’s common for me to return after a lecture break to find students crowding around the tank vying for a position to photograph them with their phones.

Young Mnemiopsis with juvenile tentacles deployed for feeding

In Long Island waters, Ctenophores are so common, we often overlook them when we’re underwater, but watching them up close, in a tank, under good lighting, we are treated to a dazzling display of lights as waves of motion in their prismatic ctenes (comb-like rows of fused cilia) send tiny rainbows streaming across their transparent bodies. They also are a fascinating animal to study in any biology course, in part because of their debated evolutionary origins. Their general morphology and the complexity of their nervous system has given biologists good reason to consider them a link between the radially symmetrical cnidarians, and fully bilateral Platyhelminthes (flatworms), however recent molecular analyses have some scientists arguing that the ctenophore lineage may actually predate the cnidarians. Wherever they belong on the tree of life, the delicate beauty of the ctenophores rivals anything I’ve seen in a marine display and I’m thrilled to be able to expose my students to them.

Incidentally, the tank is by My Reef Creations and the seawater is by ESV.

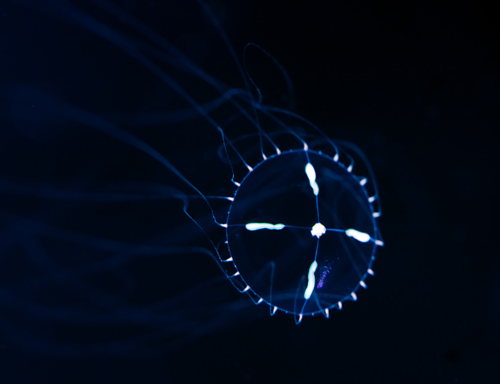

Unidentified medusa in the Ctenophore tank

0 Comments