There are numerous species of anemonefishes, more commonly known to hobbyists as clownfishes, that normally associate with a few species sea anemones. However, these same clownfishes will often times associate with non-anemone invertebrates in the absence of a suitable anemone host. It’s an odd but common occurrence in aquaria, and this month I’ll give you some information about clownfish-anemone relationships, and show you some examples of their substitute hosts.

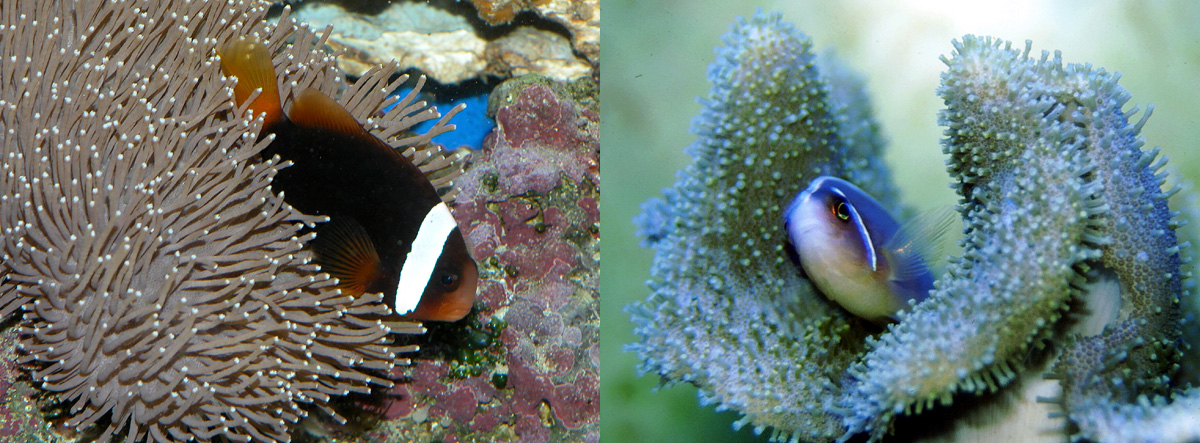

A pair of the clownfish Amphiprion perideraion, living in their host anemone, Heteractis magnifica. Below is some video of their behavior in their natural habitat.

The clownfish-anemone relationship

Due to revisions of clownfish taxonomy, various sources report different numbers of clownfish-anemone associations. So, I’ll simply say that there are about 30 species of clownfishes, all of which belong to the genus Amphiprion, with the exception of one species that belongs to the genus Premnas. Regardless of the exact number, all of these are obligate symbionts of ten species of sea anemone belonging to the genera Cryptodendrum, Entacmaea, Heteractis, Macrodactyla, and Stichodactyla. In other words, these fishes are always found living amongst the stinging tentacles of these anemones in the wild, except when very young. Clownfishes may seem to be perfectly fine without an anemone host when kept in aquaria, but this is not the case on the reefs they inhabit.

Clownfishes’ egg are typically laid under the disc of their host anemone, giving the eggs some protection, as well.

Regardless, their natural relationship is considered to be a mutualistic symbiosis, because both the clownfishes and their anemone hosts live together in such a way that both receive benefits from each other. These increase both organisms’ chances of survival and their reproductive success.

Through methods that I’ll cover below, these fishes are able avoid being stung and killed/injured by their host anemone. So, when threatened by predators, clownfishes can move into the stinging tentacles of their host, which is a very effective deterrent. Thus, the fishes are granted a safe haven when living with an anemone. According to Fautin (1991), the fishes may also feed on an anemone’s egestate, which is any partially or undigested material spat out by an anemone if it eats more than it can handle. And, the fishes’ egg are afforded some degree of protection, as they are typically laid on the substrate underneath their host anemone’s disc.

On the other hand, clownfishes oftentimes aggressively chase off any fishes or invertebrates that attempt to feed on their host, especially butterflyfishes (Fautin, 1991 and Porat & Chadwick-Furman, 2004). Likewise, as many aquarists have experienced, many clownfishes will also defend their host from human hands and arms that get too close by charging and nipping at them. This is especially so for larger species, like Premnas biaculeatus, which can be downright mean to owners and other fishes alike.

Clownfishes may also feed their host at times by taking food items into an anemone’s tentacles. Once sated in an aquarium, I’ve seen numerous clownfishes take flake food, mysis shrimp, bits of chopped meat, and even small feeder fishes to their host. I also found an article at Animal World (undated) stating that some captive clownfishes will knock or drag non-cleaning species of shrimp into their host. Host feeding has also been reported in the wild (Allen, 1972 and Fautin, 1991), but apparently is not common.

Aside from potentially delivering food items to their host, it has been found that clownfishes also provide nitrogen to their host in the form of ammonia, reducing a host’s need to feed (Roopin & Chadwick, 2009). Fishes excrete ammonia as a waste product, but their hosts can absorb it from the waters around them, where concentrations may be nearly 50% above background levels when clownfishes are present (Roopin et al., 2011).

Lastly, a very recent study by Szczebak et al. (2013), found that the constant swimming and wiggling activities of clownfishes helps to increase water movement around the tentacles of some anemones. This in turn increased oxygen available to the host, thus aiding them in yet another way.

How clownfishes can do it

Each species of clownfish will only go to certain species of host anemones in the wild, and these species-specific pairings have been well documented. In fact, you can find an excellent resource (Fautin & Allen, 1992) that covers these pairings here, and it’s free. So, as juveniles, clownfishes must find a host anemone that’s available and of the right species as quickly as possible in order to increase their chances of survival, and it has been shown that they can apparently smell them.

In the lab, Murata et. al. (1986) found that a crude mucous extract from the host anemone Radianthus kuekenthali (now known as Heteractis crispa) would elicit the attraction of the clownfish A. perideraion. It would also elicit the hallmark odd swimming pattern that clownfishes frequently display when occupying a host. They also found that a chemical they extracted from the anemone, which they named amphikuemin, would get the same results. Continuing on, they likewise found that different species of clownfishes recognized chemical cues from the same host species of anemone, and from different host species, too. So, it seems that’s how things get started. But, how do they “move in”?

It has also been experimentally shown that toxins isolated from various anemones will outright kill many clownfishes exposed to them. So, it seems clear that clownfishes aren’t getting stung and showing some sort of immunity to the toxins, rather they aren’t getting stung by their hosts (Mebs, 1994). Apparently it all has to do with the mucus slime coat the fishes produce.

Through experiments using juvenile clownfishes that had not been in contact with an anemone, Miyagawa (2010) found that several species of clownfish found in Japanese waters had an innate protection from being stung. Miyagawa also reiterated that juveniles recognize their species-specific hosts via chemical factors produced and released by them, and reported that visual cues did not seem to play a significant role in host identification. Still, it seems that no one has determined if the fishes’ slime coat contains chemicals that inhibit the discharge of an anemone’s nematocysts (stinging cells), or if it just lacks any chemicals that would stimulate their discharge (Mebs, 2009).

Clownfishes that get confused

With all that covered, now let’s get to some things that aren’t in the literature, namely clownfishes doing things in aquariums that they don’t do in the wild. They sometimes move into host anemones that don’t normally host them. They sometimes take up residence in or on various other cnidarians. And, they sometimes hang out on top of giant clams, too.

Again, in aquariums clownfishes will often find a substitute or surrogate host if no appropriate anemone is available, which is something they never do in the wild. I have searched and searched for anything covering how they are able to do this, but came up with nothing.

Sometimes this is seen as a particular species of clownfish taking up residence in an anemone that does host clownfishes, but just not that species of clownfish. For example, the bubble-tip anemone, Entacmaea quadricolor, normally hosts 13 species of clownfish, but not Amphiprion leukocranos or A. ocellaris (Fautin & Allen, 1994). However, in aquariums, these two species will oftentimes move into a bubble-tip when their normal hosts are absent. In fact, I don’t recall any A. ocellaris that wouldn’t do so, with one exception (sort of) that I’ll get to below.

Here are Amphiprion leukocranos and A. ocellaris living in bubble-tip anemones (one lacking bubbles, which is not unusual for this anemone).

In the case of A. leukocranos, Fishbase (undated) reports that this species may be a hybrid between A. chrysopterus and A. sandaracinos, and the bubble-tip anemone does host A. chrysopterus. So, maybe that has something to do with its ability to move in. As best as I can tell, there’s no explanation for A. ocellaris doing so, though.

These aren’t the only two species that do this sort of thing, either. I’ve been a reef aquarist for over 20 years now, but have never seen a clownfish of any sort take up residence in the Caribbean/Western Atlantic not-host-to-any-clownfish anemone Condylactis gigantea – except for this black and white A. ocellaris. This was around 1993, in a 55-gallon mixed reef aquarium I had. Ah, Mother Nature. Always fooling around…

Lastly, another related personal anecdote. I have some aquariums at school and put a bubble-tip anemone in one of them, along with a pair of tank-raised A. ocellaris. They never even looked at it. For months it was like they didn’t even know it was there, which is unusual in my experience. In the summer, I typically remove the few fishes from the school aquariums and bring them home where I can feed them daily without relying on an automatic feeder. So, I brought the clownfish home and put them in my anemone-less 125-gallon mixed reef tank.

When the holidays were over it was time for the clownfish to go back to school. So, I trapped them and moved them back to their original aquarium. The next day both were in the anemone. Makes no sense at all…

As I said above, clownfishes will also oftentimes move into (or just on) a variety of non-anemone cnidarians. Some of these, such as soft corals like Sarcophyton spp. and Sinularia spp. don’t sting fishes. However, some of these substitute hosts pack a very strong sting for a coral, leaving us to wonder, once again, how and why the clownfishes do this.

In some cases a substitute host, like Catalaphyllia jardinei or Euphyllia spp., does indeed have long tentacles with relatively strong stings. Thus, a confused clownfish may indeed be afforded the same protection from predators it would receive from a host anemone. I will assume that at least some of the benefits to a host covered above would be received by such a coral host, too. However, there are many other pairings that just don’t make sense. See the pictures below for some examples.

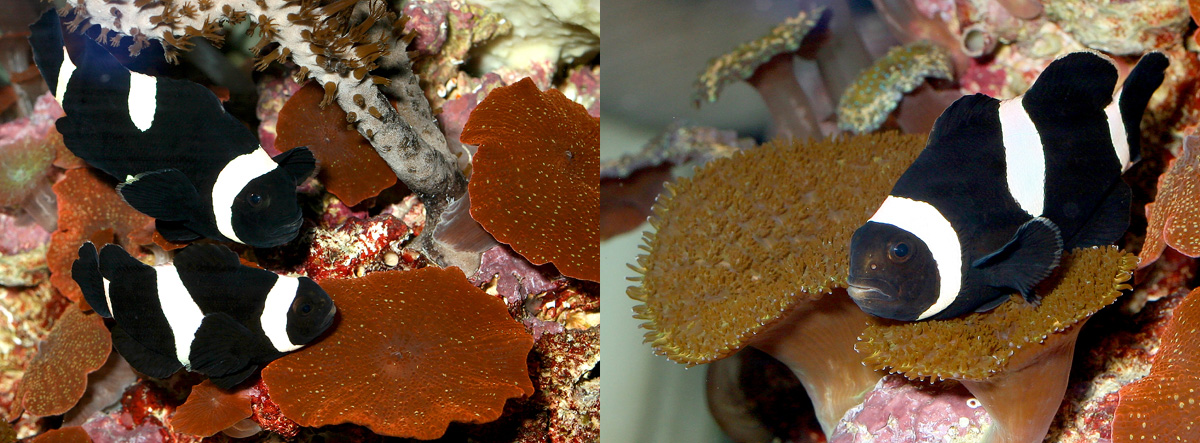

Clownfishes living amongst the tentacles of the stony coral Plerogyra sinuosa, and on top of the coralsTrachyphyllia geoffroyi and Acanthastrea sp.

As noted, some of these don’t make much sense, but they can get even stranger. As stated, they’ll sometimes decide to live on top of giant (tridacnid) clams. Even more peculiar is the fact that sometimes they’ll do this even when a more suitable cnidarian host is available. So, in these cases the clownfishes are offered no protection from predators, and any benefits of the relationship apparently go only to the “host” clam.

Tridacnid clams do not seem to be harmed when this happens. However, there is something of an acclimation period in which the clams jerk their mantle tissue inward, over and over, every time a clownfish touches them or passes over their simple eyes. Eventually the clams become accustomed to this overhead activity though, and react far, far less or not at all to a clownfish’s presence. This sort of thing happens much more than you might believe, and again, you can see the pictures below for examples.

All of this mismatching does raise one big question in my mind. While I’ve seen countless clownfishes that seemed to be perfectly happy and healthy in aquariums with nothing that could serve as a normal or abnormal host, are they really happy? If clownfishes are always found living with host anemones in the wild, and will use something like a clam as a substitute in a pinch, it just makes me wonder what it must be like to have nothing at all. Frankly, I don’t see how it could be possible for them to not be stressed by the lack of a host. But, again, I’ve certainly seen plenty that didn’t seem to be to upset about it. Food for thought…

One more thing

While it’s not specifically related to the above information, I’ve got one more thing that’s too weird to not bring up. Remember my clownfish that I moved from school to home? While they hadn’t paid any attention to the anemone or corals in their aquarium at school, within a matter of days after bringing them home they split up. One of them moved into a soft coral (Sinularia sp.) and the other moved onto a 6″ Tridacna derasa.

Soon after one of the clownfish took up residence on top of my clam, my cherub angelfish (Centropyge argi),which had never paid any attention to the clam, started hanging out with the clownfish. In fact, it started acting like the clownfish, as in mimicking its goofy movements over the clam. I certainly had never seen anything like this, and enjoyed watching them quite a lot. Pretty funny, really, and you have to see this to believe it:

References

- Allen, G.R. 1972. The Anemonefishes: Their Classification and Biology. TFH Publications, Neptune, NJ. 288pp.

- Animal World, undated. Clarkii Clownfish. URL: http://animal-world.com/encyclo/marine/clowns/clarkii.php

- Fautin, D.G. 1991. The anemonefish symbiosis: what is known and what is not. Symbiosis: 10, p.23-46.

- Fautin, D.G. and G.R. Allen. 1994. Anemone Fishes and their Host Sea Anemones. Tetra-Press, Mella, Germany. 157pp.

- Fautin, D.G. and G.R. Allen. 1992. Field Guide to Anemone Fishes and their Host Sea Anemones. URL: http://www.nhm.ku.edu/inverts/ebooks/intro.html

- Fishbase. undated. Amphiprion leucokranos. URL: http://www.fishbase.org/summary/9207

- Kai, T.Y. 2012. A clownfish and its anemone play host to their unorthodox angelfish friend. Reef Builders. URL: http://reefbuilders.com/2012/07/09/clownfish-anemone-angelfish/

- Mebs, D. 2009. Chemical biology of the mutualistic relationships of sea anemones with fish and crustaceans. Toxicon: 54(8), p.1071-1074.

- Mebs, D. 1994. Anemonefish symbiosis: Vulnerability and resistance of fish to the toxin of the sea anemone. Toxicon: 32(9), p.1059-1068.

- Miyagawa, K. 2010. Experimental analysis of the symbiosis between anemonefish and sea anemones. Ethology: 80(1-4), p.19-46.

- Murata, M., K. Miyagawa-Kohshima, K. Nakanishi, and Y. Naya. 1986. Characterization of compounds that induce symbiosis between sea anemone and anemone fish. Science: 234, p.585-587.

- Porat, D. and N.E. Chadwick-Furman. 2004. Effects of anemonefish on giant sea anemones: expansion behavior, growth, and survival. Hydrobiologia: 530/531, p.513-520.

- Roopin, M. and N.E. Chadwick. 2009. Benefits to host sea anemones from ammonia contributions of resident anemonefish. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology: 370(1-2), p.27-34.

- Roopin, M., D.J. Thornhill, S.R. Santos, and N.E. Chadwick. 2011. Ammonia flux, physiological parameters, and Symbiodinium diversity in the anemonefish symbiosis on Red Sea coral reefs. Symbiosis: 53(2), p.63-74.

- Szczebak, J.T., R.P. Henry, F.A. Al-Horani, and N.E. Chadwick. 2013. Anemonefish oxygenate their anemone hosts at night. Journal of Experimental Biology: 216:970-976. doi:10.1242/jeb.075648.

0 Comments