Prepared by Dr. William Walsh

Division of Aquatic Resources

Department of Land and Natural Resources, State of Hawai’i.

In the November 2004 edition of this column I reviewed Scott Michael’s article “Seven Steps Responsible Aquarists Should Know.” In it he reported “Researchers from the University of Hawaii, Hilo, compared the abundance of seven popular aquarium fish between locations where collecting occurs and areas where collecting is prohibited. They concluded that in areas where fish collecting occurs, these seven species are less abundant than in protected area. For example, at sites where regular collecting occurs, there were 47% fewer yellow tang (Zebrasoma flavescens) than in areas where collecting was not allowed.”

I added that I had quoted Brian Tissot, a Washington State University marine ecologist, who reported more than three years ago (“Something’s Fishy,” The Smithsonian, December 2001) that in Hawaiian waters targeted by aquarium collectors, populations of eight of the most popular species had fallen by 38 to 57 percent. (Advanced Aquarist Online Magazine, March 2002).

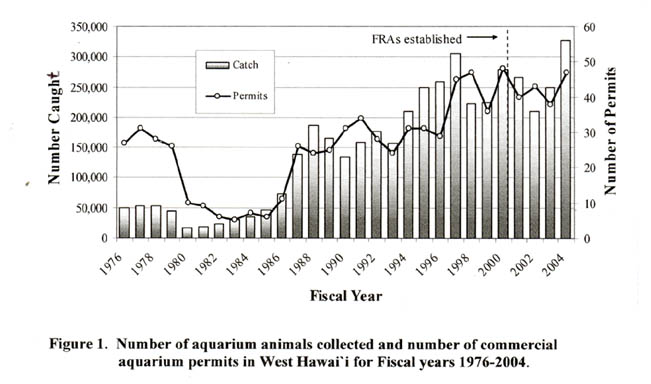

The most recent data from Dr. William Walsh, marine biologist of the state’s Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR), indicates that for the fiscal year 2004, more than 300,000 reef fish were collected from Hawaii’s reefs for the aquarium trade – 84% of which are yellow tangs, yielding a figure of well over 250,000 yellow tangs taken for the year. Other species are taken in smaller numbers. Virtually all of these fishes are taken from the West, or Kona, Coast of Hawaii, where I live. Take totals started rising significantly in the late 1980’s and early 90’s, both for fish taken and fishing permits requested and issued.

The depletion of reef fishes, especially yellow tangs, brought strong negative reactions from other reef users, especially snorkelers and scuba divers, leading to community pressure to close the entire coast to all aquarium collecting. A petition recommending this action collected more than 4,000 signatures. In April, 1999, DAR held what turned out to be its largest-ever local hearing, drawing almost 900 testimonies. Of these more than 90% were in support of Fish Replenishment Areas (FRA’s), closed to aquarium collecting, and covering a minimum of 30% of West Hawai’i’s coastline.

This strategy is close to one Scott recommends, stating as one of his “Seven Steps” that marine aquarist should “Encourage and support the development of reserve areas where no fishing of any sort occurs. These types of locations are known as Fish Replenishment Areas (FRAs) where adult fish can populate vast tracks of coastline with their young.

Studies have shown that an FRA is an easy way to ensure the preservation of fish populations on coral reefs.”

This fisheries management technique has been put into practice here. In response to heated community pressure, approximately one third of the western, coast of the Big Island of Hawaii has been set aside as FRA’s closed specifically to aquarium collection. These FRA’s are in addition to other partially or fully closed marine management areas.

The location of the FRAs were established after consultation with all concerned user groups, including aquarium fish collectors, by a community-based Fisheries Management body, the West Hawai’i Fisheries Council (WHFC) which was convened in 1998 and continues to function and on which I serve. The areas were set aside in 1999, with a mandate that the University of Hawaii conduct annual surveys of aquarium fish populations and that a major evaluation of the effectiveness of the program was to be done in 5 years. This major evaluation has just become available to the public and is the basis for the information reported in this month’s column.

TABLE 1. Overall FRA effectiveness for the top ten most aquarium collected fishes.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Mean Density* Before | Mean Density* After | Overall % Change in Density# |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yellow Tang | Zebrasoma flavescens | 14.7 | 21.8 | +48% |

| Kole Tang | Ctenochaetus strigosus | 31.0 | 33.3 | +7% |

| Achilles Tang | Acanthurus achilles | 0.24 | 0.30 | +26% |

| Clown Tang | Naso lituratus | 0.75 | 0.84 | +11% |

| Chevron Tang | Ctenochaetus hawaiiensis | 0.22 | 0.23 | +2% |

| Longnose and Forcepsfish | Forcipiger spp. | 0.73 | 0.77 | +6% |

| Fourspot Butterflyfish | Chaetodon quadrimaculatus | 0.03 | 0.06 | +100% |

| Ornate Butterflyfish | Chaetodon ornatissimus | 0.87 | 0.75 | -14% |

| Multiband Butterflyfish | Chaetodon multicinctus | 5.71 | 5.02 | -12% |

| Hawaiian Cleaner Wrasse | Labroides phthirophagus | 0.88 | 0.73 | -18% |

* Mean density = Number per 100 square meters

Table 1 shows that the five major species collected, accounting for 96% of the total reported catch, all showed substantial increases in population density since the FRAs were established five years ago. It is also clear that this management technique is not necessarily a panacea.

Three species, two of them Butterflyfishes and the third the Hawaiian Cleaner Wrasse have continued to decline even in the protected areas. Kole Tangs and Chevron Tangs, the latter the second most captured species have shown only modest recovery. The same is true for the Forcipiger species.

Other studies have indicated that large FRAs with high initial densities of adult fish and containing wide reefs with the high coral cover critical for juveniles are essential ingredients for successful population recovery.

The report concludes with a set of 19 Recommendations. These include the maintenance of a dedicated monitoring program with sites surveyed 4 times per year with two of them during the summer juvenile recruitment period and the need to establish species-specific strategies for rare and vulnerable species such as the Flame and the Banded Angelfish. The report also contains recommendations for the continuation and expansion of community based resource management typified by the WHFC. There is also a need for increased control over aquarium collectors by establishing a limited entry fishery and demanding increasing reliability of catch reports. The recommendations also stress the necessity of recognizing ecological connections and of feeding and resting patterns between deeper and shallower water zones in the establishment of FRAs.

Dr. William Walsh and Hawai’i’s Division of Aquatic Resources are to be congratulated for producing a document rich in detail and analysis on this important fisheries management technique. It contains important specific direction and advice for those, both fisheries management scientists and concerned citizens of coastal communities who wish to participate in the further utilization of the successful FRA strategy.

Note: All Figures and Tables are taken from this Report

0 Comments