In the last few decades, aquarists have steadily refined marine fishkeeping. These innovations include improved collection/handling/shipping procedure, more effective aquarium water filtration/treatment technologies, and a better understanding of marine fish nutrition/immunology, as well as a growing preference for systems that are specialized for keeping the flora and fauna of distinct ecological communities (biotope aquaria, if you will). Having access to better information, more advanced equipment, and healthier specimens, aquarists might find that some groups of fishes that were once thought to be “difficult” or “delicate” can actually be kept with relative ease, provided that certain special needs are properly addressed. One such group may be the sand tilefishes.

An aquarium containing sand tilefish should be completely covered to prevent escapes. Photo by reefhotspot.com.

Members of this group–particularly those of the genera Malacanthus and Hoplolatilus–are highly prized aquarium fishes. Reasons for this are many. They are quite attractive, having a unique, exotic body form in addition to (at least in the case of certain species) handsome coloration and patterning. They are highly active and display a number of rather interesting behaviors. They are endearing creatures, endowed with considerable charm and intelligence.

Nevertheless, even though this group is fairly abundant and widely distributed, it remains underrepresented in the aquarium hobby. Prices (with ranges that tend to vary between species) are comparatively higher among marine ornamental fish, despite a limited demand. Demand for these creatures appears to be limited mainly by the perception that they are challenging to keep. In that successfully maintaining them does indeed require a considerable amount of planning, resources, and good luck, such a perception is–as we shall see–at least partly justified.

Sand Tilefish in the Wild

The family Malacanthidae is an ecologically diverse group that can be found in the temperate and tropical marine (and in at least one case brackish) waters of the world. While some tilefish can reach a length of 125 centimeters (Lopholatilus spp.), those species of interest to most aquarists (certain members of the subfamily Malacanthinae) will likely not exceed 20 centimeters (Hoplolatilus spp.) or 60 centimeters (Malacanthus spp.). Morphological variance among members of Hoplolatilus and Malacanthus is slight. The body plan of the two genera is slender, elongate, and fusiform. Dorsal and anal fins are simple and short, running continuously along the length of the body. A blunt head and heavy, upturned, terminal jaw gives them a grumpy appearance.

Despite superficial similarities, tilefishes are not closely related to gobies (such as this Ptereleotris hanae). Photo by thatfishplace.com.

Success with sand tilefish depends largely upon ones ability to obtain specimens that have been carefully harvested by a competent collector. Photo by Eddie Hanson.

Sand tilefish inhabit sand- and scree-covered flats, reef bases, and reef slopes. They typically occur at considerable (at least for reef-associated fishes) depth; they are seldom found above 5 meters of depth, and are typically found at depths of 25-65 meters.

Sand tilefish are great excavators and builders. These fishes construct (sometimes huge and elaborate) burrows for their protection. These structures might serve primarily as a safe place to sleep; if threatened during their waking hours, a tilefish is as likely to dart off into the distance as it is to dive into its burrow. Though they are disinclined to defend their homes from fishes of other species, they can be quite scrappy with neighboring conspecifics (squabbling over territory and even stealing building materials from each others’ burrows).

Sand tilefish feed mainly on small crustaceans and crustacean larvae.

While much remains unknown about their reproductive habits, they are believed to be pelagic spawners that form long-term monogamous pairs.

Sand Tilefish Species of Interest

Malacanthus brevirostris (banded blanquillo) is found in seaward, barren, open sandy areas at 14-45 meters of depth throughout Oceania, the Tropical Western Pacific, the Great Barrier Reef, the Northern and Western Indian Ocean, and the Red Sea. This species reaches 30-60 centimeters in length, requiring at least 600 liters of tank volume.

Malacanthus latovittatus (blue blanquillo) is found on the seaward side of reefs at 5+ meters depth throughout the Temperate and Tropical Western Pacific, and the Northern and Western Indian Ocean. It has been observed in brackish waters near the end of Papua New Guinea’s Goldie River. Its pattern changes substantially with maturity; juveniles appear to mimic Hologymnosus annulatus (ring wrasse). This species reaches ~45 centimeters in length, requiring at least 500 liters of tank volume.

M. latovittatus. Photo by thatfishplace.com.

Malacanthus plumieri (sand tilefish) is found in a variety of sandy or rubbly habitats, nearshore down to 150 meters of depth throughout the Temperate and Tropical Western Atlantic, as well as the Tropical Eastern Atlantic. This species reaches ~60 centimeters in length, requiring at least 600 liters of tank volume.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DcDRJknCOe4

M. plumieri at the Key West Aquarium. Video by Sirhiss9.

Hoplolatilus chlupatyi (flashing tilefish, chameleon tilefish) is found near reef bases at ~30 meters of depth throughout the Tropical Western Pacific. It is capable of rapid changes in coloration. This species reaches ~15 centimeters in length, requiring at least 200 liters of tank volume.

H. chlupatyi can change its color from salmon to blue, green, orange, or purple in an instant. Photo by Felicia McCaulley.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JHzKlCl49UY

H. chlupatyi feeding. Video by djames4444.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mO_KZbLEhtY

H. chlupatyi flashing. Video by SuperGDetroit.

Hoplolatilus cuniculus (dusky tilefish) is found in sandy to muddy outer reef slopes at 25-115 meters of depth throughout Oceania. This species reaches 9-15 centimeters in length, requiring at least 100 liters of tank volume.

Hoplolatilus fourmanoiri (spotted tilefish, yellow-blotched tilefish) is found in silty sand flats at 5-55 meters of depth throughout the Tropical Western Pacific. This species reaches 14-20 centimeters in length, requiring at least 200 liters of tank volume.

H. fourmanoiri. Photo by thatfishplace.com.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=66xLbMqnCLE

H. fourmanoiri hovers over aquarium bottom. Video by lunner.

Hoplolatilus fronticinctus (pastel tilefish, stocky tilefish) is found in sandy reef bases at ~60 meters of depth throughout the Tropical Western Pacific, the Great Barrier Reef, and the Northern and Western Indian Ocean. It can construct rubble mounds that exceed a meter in height. This species reaches ~20 centimeters in length, requiring at least 200 liters of tank volume.

Hoplolatilus luteus (yellow tilefish) is found over flat, soft, silty bottoms at 30-35 meters of depth throughout the Indo-Pacific. This species reaches ~11 centimeters in length, requiring at least 100 liters of tank volume.

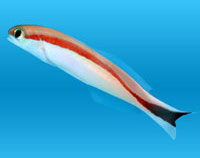

Hoplolatilus marcosi (redstripe tilefish, redback tilefish, Marcos’ tilefish, skunk tilefish) is found in sandy rubble zones at 18-80 meters of depth throughout the Tropical Western Pacific. This species reaches 12-20 centimeters in length, requiring at least 100 liters of tank volume.

H. marcosi. Photo by thatfishplace.com.

Hoplolatilus purpureus (purple tilefish) is found in muddy to rubbly outer reef slopes at 18-80 meters of depth throughout the Tropical Western Pacific. This species reaches ~14 centimeters in length, requiring at least 200 liters of tank volume.

H. purpureus. Photo by thatfishplace.com.

Hoplolatilus starcki (Starck’s tilefish, purple-headed tilefish) is found on steep, rubbly seaward slopes at 21-105 meters of depth throughout Oceania. Juveniles are completely blue, and seem to mimic Pseudanthias pascalus (purple queen anthias) with which it schools. This species reaches 14-20 centimeters in length, requiring at least 200 liters of tank volume.

H. starcki. Photo by thatfishplace.com.

Sand Tilefish in the Aquarium

Tilefish were largely ignored by marine aquarists in the 50’s and 60’s (indeed, some were not even discovered and described until the 70’s). While modest numbers of specimens began to trickle into the trade through the 80’s and 90’s, attempts to keep them for an appreciable length of time were usually met with failure. Having been marked with the dubious distinction of an impossible-to-keep aquarium fish, they continue to receive minimal attention in the hobby; even many contemporary aquarium science authors suggest avoiding them altogether. All the same, as indicated by indubitable successes reported on numerous online forums, recent improvements in aquarium technology/methodology have greatly increased ones chance of success with these fishes. All anecdotal evidence from these and other sources suggests that extended survivorship of captive sand tilefish requires that a host of special husbandry needs is addressed.

First and foremost, sand tilefish can be kept only in roomy enclosures. Affording them with plenty of open swimming space will ensure that when they get spooked (they will get spooked) they will be less likely to injure themselves by colliding with rockwork or the aquarium panels. Similarly, a very secure, tight-fitting lid must be used to prevent escapes.

The intense lighting typical of most reef aquaria will cause undo stress in these fishes; low or moderate lighting is best. Lighting should increase/decrease gradually throughout the photoperiod as to avoid startling them. Nocturnal “lunar lighting” can be used to reduce “night fright.”

The bottoms of tanks housing sand tilefish should include at least one large, open, sandy area. The substrate must be at least a few inches deep, though a depth of 6 inches or more is preferable. While each sand tilefish species may each prefer a rather specific substrate type, a fine sand/course rubble mixture will probably suffice.

By all accounts, sand tilefish simply do not tolerate suboptimal water quality. It will be imperative to install an appropriately sized, high-capacity filtration system on a system housing sand tilefish. Such a system should be completely cycled and stabilized well before tilefish specimens are introduced.

Aside from ensuring that they are provided with an appropriate living space, the most important factor in success with keeping sand tilefish appears to be obtaining specimens from a quality dealer. Unfortunately, collectors have a long history of using sodium cyanide to harvest these wily, evasive creatures. During capture, their panicking and intense struggling can result in serious injury, especially if they must be extracted from their burrows. As with many other deepwater reef fishes, further injury can be inflicted if certain steps are not taken to mitigate decompression-related trauma. They are notoriously poor shippers (indeed, many online retailers do not cover them under normal “live arrival” guarantees), and will be much more likely to succumb to shipping stress if exporters/distributors/wholesalers/retailers have not packed them with the greatest care. One should be able to evaluate the health of a prospective specimen before purchase (perhaps 3-4 weeks) to ensure that it is free of disease and physical damage, is alert, and is eating well; where this is not possible, new specimens should be quarantined prior to introduction into a display. Parasitic infestation–to which these fishes are particularly prone–is especially problematic due to the hosts’ own sensitivity to many common remedies (e.g., copper sulfate).

Ones odds of success with sand tilefish will be greater if specimens are added in pairs. Ideally, they will be among the first fish added to a tank, so that they not be subjected to any competition or harassment during the critical period of adjustment. This nervous, flighty fish is not comfortable in crowds–much less so with larger, hyperactive, or aggressive tankmates. Aquarists are encouraged to leave the lights down (or off) and refrain from working in or around the aquarium for the first few days of adjustment.

Feeding a new sand tilefish can be challenging. The initial response of newly captive specimens to feeding seems to differ between individuals. One should be prepared to offer a variety of quality (preferably live) foods. Artemia, bloodworms, glass worms, mysis, daphnia, and amphipods are excellent starter foods here. Once a captive feeding regimen has been established, meaty foods such as chunks of krill or clam might be accepted. Despite their reputation as finicky eaters, they can become downright gluttonous upon adjustment to captive life, even feeding from their keepers’ hands. These highly active, high-strung fishes require a substantial amount of food, and should be fed at least a few times daily.

Unless it is absolutely necessary to do so, one should never disturb a sand tilefish’s burrow.

Conclusion

Sand tilefishes of the genera Malacanthus and Hoplolatilus are extraordinarily interesting and beautiful ornamental fishes. It is well established that members of this group have a low extended survivorship in conventional marine aquaria; still, many aquarists are finding that success with these fishes is quite possible, provided that certain important aspects of their ecology are reflected in their captive care. Demand for (and success with) them will almost certainly increase, as heavily fed, modestly illuminated, NPS (non-photosynthetic) deepwater reef systems continue to gain popularity. There is much to be learned about this valuable aquarium fish (reports of captive spawns of some sand tilefish species have certainly been encouraging); clearly, the suitability of these intriguing animals for the home, and public, aquarium has yet to be fully demonstrated.

Sources

- Gilbert, Carter R. and James D. Williams. National Audubon Society Field Guide to Fishes. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 2002.

- Smith, C. Lavett. National Audubon Society Field Guide to Tropical Marine Fishes. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1997.

- Lieske, Ewald and Robert Meyers. Coral Reef Fishes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Burgess, Dr. Warren E., Herbert R. Axelrod, and Raymond E. Hunziker III. Dr. Burgess’s Atlas of Marine Aquarium Fishes. 3rd ed. neptune City, NY: TFH Publications, 2000.

- Debelius Helmut. Fishes for the Invertebrate Aquarium. Stuttgart, Germany: Eugene Ulmer GmbH & Co., 1989.

- http://eddie-coral-adventures.blogspot.com/2008/06/gone-fishing-part-3.html

- http://www.messersmith.name/wordpress/2009/04

- http://aquariumadventures.blogspot.com

- http://fishbase.org

0 Comments