Like many marine hobbyists I have a great fondness for wrasses, which is quite fortuitous as there are so darn many of them, if you pick a chunk of sea anywhere on the planet, the chances are there will be a wrasse in it.

The wrasse family, the labridae, is composed of over six hundred species that range from the enormous Napoleon Wrasse (Cheilinus undulatus, sadly a threatened species), to the diminutive possum wrasses (Wetmorella sp.).

Interestingly though, the juvenile stage of C. undulatus bears a very close resemblance to the juvenile stages of many other, far smaller wrasse species, notably some Anampses and Bodianus species, and difference is a common trait in the clan. Sometimes, differences in colouration, body shape and behaviour, between adult and juvenile phases, are so pronounced that specimens appear to the layman as if they were entirely unrelated species, in fact appearing as if they were in different genera.

We are familiar with many fishes in the wild and in the aquarium undergoing transformation from juvenile to adult phases and of course changing gender. This behaviour is remarkable and requires someone with far more knowledge (and magazine space), than I to explain in every case, suffice it to say: evolution, that slow and steady succession of fortuitous mistakes is a wondrous thing. It is in the Labroids, I would suggest, most noticeable and most remarkable.

However, in the hands of uninformed and unprepared aquarists and perhaps the less conscientious dealers, fishes that start out as ‘cute’ can rapidly grow into tank busters and aquascape destroyers. Species such as Coris formosa, C. aygula and C. cuvieri, for example, should be left in the ocean. Rockmover wrasses (Novaculichthys taeniorus) are also cute as juveniles but when they reach 30cm and start hurling rockwork about they become a nightmare. I am still astounded that they continue to be imported and would urge everyone to stop stocking them and buying them.

C. Formosa, cute now, but just wait. In the wild it will reach 60cm! It is not suited for captivity in my opinion.

Wrasses of the genus Halichoeres

Size problems tend not to be an issue with Halichoeres wrasses, in fact they are near perfect as aquarium fish, and mostly they are small enough, with some exceptions, to feature in most medium sized and larger systems. Aquarists should be wary of purchasing some species though: the checkerboard wrasse, H. hortulanus can reach 25 cm in the wild and H. podostigma and H. chloropterus are reported to reach 18cm. Fortunately most species top out in the 12-15cm range at maximum, with some a little smaller. As the fishes age they will ‘bulk out’ and their body profile will become deeper, top to bottom, they will also lose a certain amount of the ‘cute’ factor that the juveniles possess. Some species such as H. hartzfeldii will come to more closely resemble their cousins the parrot fishes in appearance as they mature.

H. chloropterus, (juv.). The jade or dark-blotch wrasse. One of the many species that shows marked sexual dichromism when mature.

The genus Halichoeres derives its name from ‘salt’ or ‘sea pig’. This is one of those scientific names that derives from Greek rather than Latin – ‘halio‘ and ‘choiros‘ combined gives us Halichoeres. I have always assumed that ‘salt pig’, refers to the ‘snouts’ of this genus, which do indeed resemble the upturned nose of the pig, though I’m sure if I’m wrong on this I will be corrected.

The genus Halichoeres has become enlarged since some of the best books on the subject were first written (Rudie Kuiter’s Fairy & Rainbow Wrasses and their relatives, for example), and is now listed as containing 82 species. Some species such as H. zulu were added as recently as 2010 and no doubt other revisions, additions, amendments and discoveries will occur.

Halichoeres wrasses all share the same basic body pattern and similar dentition, though some species possess enlarged canines in the upper jaw which is sometimes an adult or purely male feature,according to Rudie Kuiter. Data bases such as FishBase provide far more information about morphology than I can here and are maintained by experts with far more knowledge than I possess, so please consult these resources to learn more about numbers of rays in dorsal fins and so forth.

H. rubricephalus (red-headed wrasse, male). The top specimen is in transition, the lower is a larger, sexually mature adult.

The genus also shares, as do members of several other genera such as Macropharyngodon, that remarkable and highly attractive patterning around the head and gill covers that can be so very variable between species. This patterning can be more pronounced in the male of some species or in the case pf H. rubricephalus, absent and present only in the female of the species. Personally I find the female H. rubricephalus one of the most attractive of all the Halichoeres wrasses, given that the patterning extends down the fishes entire body. The male, who has, as the name implies a bright red head has presumably developed this characteristic through the evolutionary process of sexual selection, though if I am in error I hope someone will let me know.

Most Halichoeres wrasses are found in tropical waters, approximately three quarters are found in the Indo West Pacific with around twenty species found in the eastern Pacific and Atlantic. Some have limited geographic ranges such as H. marginatus which is only found in the Red and Arabian Seas, though most are more widespread.

They are busy fish, always on the move and always to be found flitting over the reef on the lookout for small crustaceans, polychaetes and pretty much anything else edible including planktivorous food. It appears that the entire genus will present few if any feeding issues in captivity. Mine will take everything from flake to nori, though mostly they prefer frozen or live crustacean fare. They seem to do well on it as well, and of all the fish I have ever kept they have been the ones to grow at the fastest rate, and always the ones to remain healthy and resist disease.

I would suggest they are some of the hardiest fishes I’ve come across. Around a year ago my main tank suffered a wipe-out, every fish (or so we thought) was killed when a combination of circumstance and my own stupidity meant my ORP probe was exposed to air and my ozoniser was allowed to remain ‘on’ for a few hours. The next day as I looked into my once beautiful system I noticed a flash of yellow and sure enough my ‘bomb proof’ H. leucoxanthus had emerged from the substrate it had been hiding in, and was swimming about groggily. I’ve learnt my lesson and have never used ozone since.

In captivity the genus will welcome an open rockwork structure, within which the fishes can hunt and explore. Watching them study the rockwork and watching their highly mobile eyes scrutinise every inch of rock and substrate is very enjoyable. Some individuals will reward you with removal of some troublesome pests, but don’t expect adding one will be a guaranteed way to deal with your flatworm problem, whilst it might, it might not get ’em all. They will though, make a dint into any population of polychaete worms that exist in your tank that for one reason or another are active in the day time. They may also take small ornamental crustaceans. I believe that shrimps such as the ubiquitous cleaners will be safe, but small species such as Sexy shrimp will be bashed against the rockwork and disposed of quickly without a second thought.

Halichoeres wrasses are fish that can eat and eat and eat and they may also try to eat fan worms, small echinoderms and small snails. Stomatella snails are a firm favourite. However, I have yet to come across a Halichoeres wrasse that has eaten or even shown any interest in clam mantles, large or small polyped corals, soft corals or gorgonians for that matter – Always a good thing in a fish!

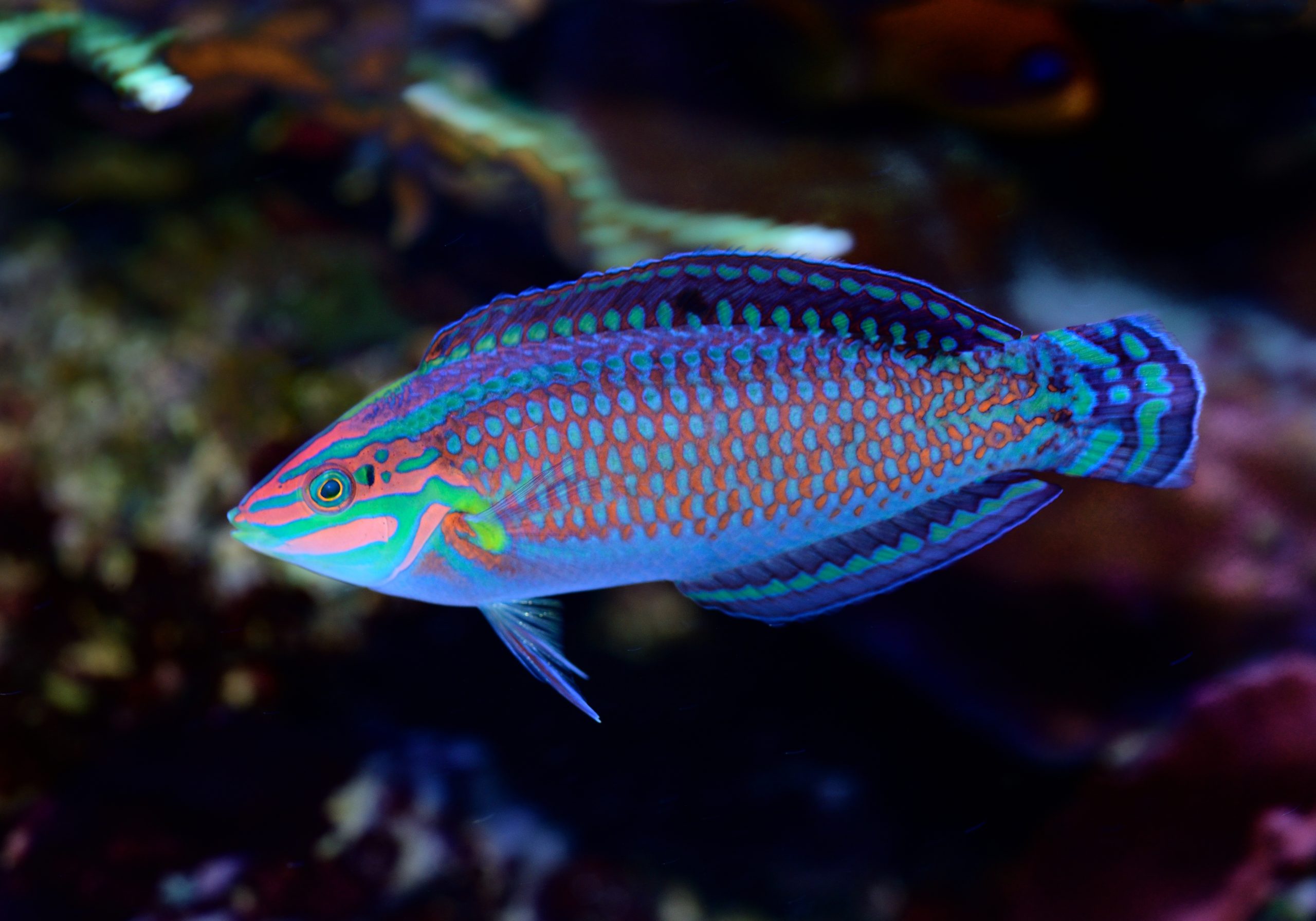

H. ornatissimus (ornate or Christmas wrasse), my specimen (younger than this larger fish), has been christened ‘Noel’, for predictable and unimaginative reasons.

Halichoeres wrasses do have one absolute requirement and that is a deep sand bed in which to bury themselves at night or when they feel threatened. At least two inches would be my recommendation and due to their burrowing nature it might be wise to avoid using very fine substrate to limit the amount of material displaced into the water. Equally, coarse and sharp materail should be avoided as it may cause injury to the fish as it forces its way into the substrate. Standard coral sand without large, sharp grains will be ideal. As noted the fishes may burrow when spooked and according to some authors may jump from uncovered tanks in some situations, though I haven’t witnessed that behaviour myself. The fishes may also disturb the substrate on occasion to flush out and uncover potential prey items, again another reason to forgo very fine substrate material.

In the wild many halichoerids will live in loose haremic aggregations and some can be kept in small groups in the aquarium if added together, I have seen groups of H. chrysus happily ignoring each other in a large tank and they looked great, but harmony cannot be guaranteed within and between species groupings. So unless you have a large tank I’d keep just one Halichoeres and enjoy it alongside other wrasses perhaps.

Another beauty, H. richmondi, quite similar to H. leucurus and H. melanurus but recognised by the chain-like body stripes.

Halichoerids tend towards the peaceable side of the behaviour divide, they are not particularly territorial in general, nor will they become belligerent and bully other fish in my experience. Though as noted, one Halichoeres that is well established in a tank is unlikely to welcome another, later addition.

Of all the wrasses, and indeed, of all the fish we can put in our tanks, these are ideal. They are easy to feed, common place (mainly) in the wild, adaptable and hardy. The only real question, is which one will you choose?

0 Comments