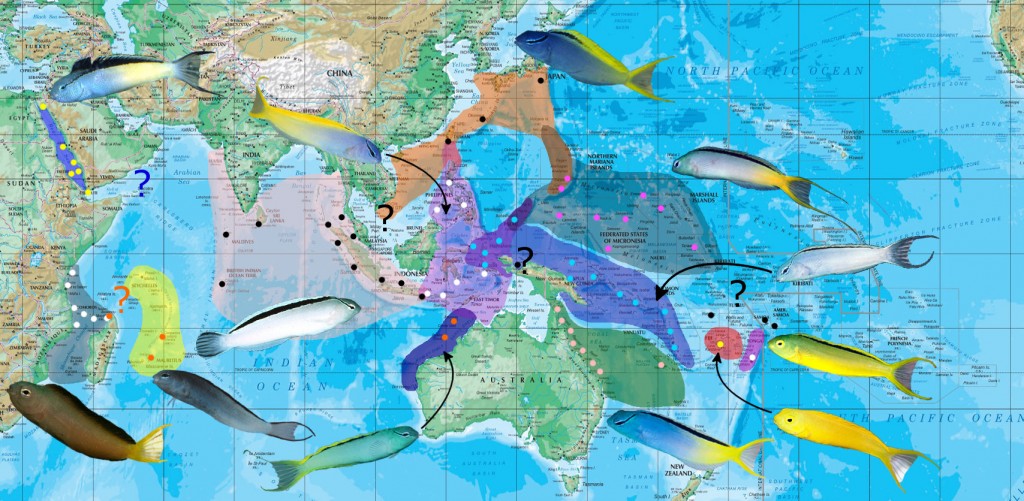

M. atrodorsalis, oualanensis, tongaensis, smithi, fraseri, mossambicus & nigrolineatus

The atrodorsalis species complex represents the only widespread Indo-Pacific species group in the genus and is comprised of numerous endemic taxa, both scientifically described and undescribed. What all these species share is a similarly unstriped appearance, a mimicry relationship with Plagiotremus blennies, and a biogeography in which the various phenotypes appear to fit together like a phylogenetic jigsaw puzzle.

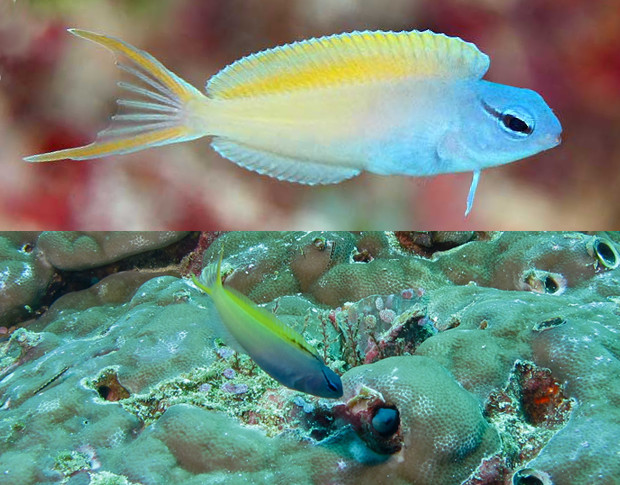

Variation in M. nigrolineatus, all from Red Sea. Credit: John Rochester, Richard Field, Arne Kuilman

In the Red Sea we find the most aberrant member, M. nigrolineatus, which can be recognized by its blue and yellow coloration and from the unusual black line which emanates behind the eye and proceeds posteriorly to the upper margin of the caudal peduncle. The location of this stripe doesn’t seem to match well with any of its congeners, giving this blenny the sort of sui generis appeal rare fish enthusiasts get excited for. It has been exported on rare occasions, and captive-bred specimens are on the books, but, in general, this is not a common find in the aquarium industry.

There is also surprisingly little photographic documentation for such an ostentatious fish given how well-studied and photographed the Red Sea is. Most specimens identified online as M. nigrolineatus are in fact Ecsenius gravieri, a remarkably accurate mimic.

The coastline of Eastern Africa is home to M. mossambicus, a rather drab grey and black species accented with a bright yellow caudal fin—the only Indian Ocean species lacking black margins to this fin. There is little known about the true extent of this fish, with Mozambique being the southernmost record. It has been documented as far east as Northern Madagascar, where it may or may not co-occur with M. fraseri, a species primarily known from Mauritius and Réunion Islands. This poorly known Mascarene species differs in having a clear anal fin (black in mossambicus) and a clear caudal fin with black margins. M. fraseri has not been exported yet for the aquarium trade, though collection takes place in both Mauritius and Northern Madagascar.

M. smithi, showing typical soft coral and algae-rich habitats. Specimens from Similan Islands and Sumatra. Credit: Takeshi Omura, Dive to Blue, Josh Hatton

M. smithi is an elegant fish which is woefully overlooked by aquarists—when it comes to predominantly white coral reef fishes, there are few which can rival smithi for its combination of beauty and affordability. With the exception of M. anema, there is no other species which has a rounded caudal fin, but, distinctive though this may be, there is no reason to believe smithi is anything but a variation on the atrodorsalis Group theme. While it has been captive-bred, many specimens encountered will be wild-collected from Sri Lanka or the Maldives. There is little indication of any meaningful physical difference between the Central and Eastern Indian Ocean populations, but genetic study is warranted to confirm their conspecificity.

Juvenile M. cf atrodorsalis from Mactan, Philippines and mature specimens from Borneo. Note the unmarked dorsal fin of the juvenile. Credit: kiss2sea & Bernard Dupont

Moving into the Pacific Ocean we find a confusing morass of taxonomic uncertainty. When the many variations from this region were last reviewed in 1987, Smith-Vaniz took an inconsistent approach to their taxonomy, raising some phenotypes to species-level, while lumping many others under the catchall “atrodorsalis”. With the advantage of far greater photographic documentation from throughout the Pacific range, a more accurate assessment of the true phylogeny can now be attempted.

The Japanese cf atrodorsalis, from Okinawa. Note the prominent juvenile pattern. Credit: uruludive & nakamura

There are enough consistencies to infer what the common ancestor of all these variations likely looked like: a blue and yellow fish with a black stripe in the dorsal fin. This is essentially what we see in all but a few isolated locations. The confusion has come from an inadequate understanding of the consistent and inconsistent variations on this ancestral blueprint seen in the numerous ecoregions comprising the West and Central Pacific.

The Micronesian cf atrodorsalis. Note the distinctive juvenile coloration, from Majuro. Adult males from Guam & Yap. Credit: mdx2, Dave Burdick, Judy A. Bennett

In much of Indonesia, Borneo and the Philippines we find a phenotype with a weak development of the dorsal fin stripe, with it restricted to the anterior third of the fin. As juveniles, this marking is absent. When we look at populations from Japan, we see a very similar fish, but the juveniles from this region always possess a strong black marking in the anterior dorsal fin. Furthermore, the line posterior to the eye is typically twice the thickness of Indo-Philippines specimens (though mature specimens see this line turn far thinner).

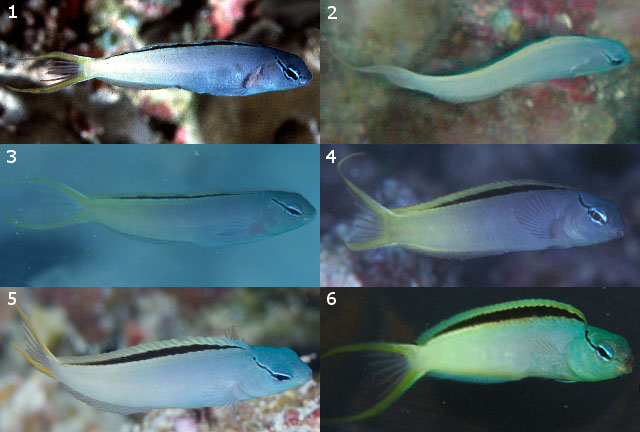

The Melanesian cf atrodorsalis. Note the grey body and black dorsal fin. 1=Halmahera, 2=Manado, 3-5=Palau, 6=Vanuatu. Credit: John Randall, Eiji Kodato, yutaka diver, Takahisa Fujishiro, Mark Rosenstein, SRS Vanuatu

Specimens from Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, Palau and east as far Northern Sulawesi are recognizable by the lack of yellow posteriorly, as well as a strong black stripe extending the length of the dorsal fin. Smith-Vaniz reports it occurring on the northern coast of Ceram, with the Indo-Philippines phenotype found on the southern side of this island. Whether the two ever occur in sympatry or hybridize is unknown, but likely (see image below).

A possible hybrid of the Indo-Philippines and Melanesian populations. Note the intermediate dorsal fin stripe and light yellow coloration. From the Banda Sea. Credit: Gerry Allen

We find another consistently different phenotype present in Western Australia, the Coral Sea, and Micronesia—three ecoregions which typically have their own endemic ichthyofauna. Their shared coloration (a blue and yellow fish with a long black dorsal stripe) is likely to represent an ancestral state which has differentiated relatively little. Unfortunately, there is minimal photographic documentation to allow for more subtle interpretations. Only a single image seems to exist from Western Australia, with little more available for Micronesia.

M. cf atrodorsalis from Cenderawasih Bay, New Guinea. Note the black margins of the caudal fin and grey coloration. Credit: Gerry Allen

Smith-Vaniz studied numerous specimens from Micronesia, and painted a confusing picture which seems at odds with the general biogeographical pattern known from this region. Presumably, this can be chalked up to his early study relying on preserved specimens or perhaps misinterpreting some of the developmental changes in color patterns which are common to this genus.

M. cf atrodorsalis from Eastern (above) and Western Australia. Note the brighter yellow of the dorsal fin and greyer body of the western population. Credit: Gerry Allen & Rudie Kuiter

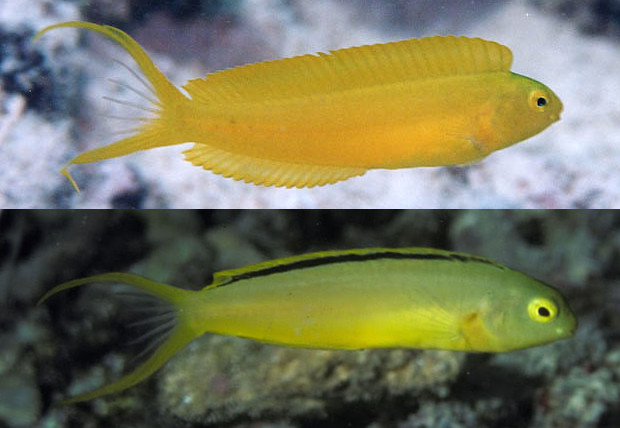

Lastly, there is a pair of unusually xanthic phenotypes restricted to the Fijian and Tongan waters. The popular Canary Blenny, M. oualanensis, is known only from Fiji, and, unlike others in this group, it has an entirely yellow body and unmarked dorsal fin. To the east in Tonga, M. tongaensis shows the long black dorsal fin stripe of neighboring regions, but the body is an enigmatic chartreuse anteriorly. It is almost as if this population is trying its hardest to be like oualanensis, but it just can’t quite get there. What we see in tongaensis is little more than the Micronesian phenotype which has had the gene(s) controlling for the light-blue anterior dialed way down, while in Fiji the genes controlling for this blue coloration, as well as those controlling the black stripe, are both completely non-expressed.

M. oualanensis and tongaensis. Note the dorsal fin stripe and chartreuse coloration of the latter. Credit: Yoshimi Kyakuno

To sum this all up, there are likely to be eight distinct regional variations of the “atrodorsalis” theme which are worthy of species recognition. Note that the type locality for the species is Samoa, with specimens from this region appearing nearly identical from those seen elsewhere in the Central Pacific. Samoa is a region whose fauna is often quite similar to nearby Fiji and Tonga, which raises the question as to whether these Samoan atrodorsalis are more directly related to oualanensis/tongaensis than the Micronesian cf atrodorsalis. Confirming this and other questions will require a greater effort in documenting the nuances of their color differences from throughout their respective ranges and especially so in areas of overlap, as well exhaustive genetic study utilizing next-gen techniques.

0 Comments