By Lemon TeaYK

The family Labridae advertises a bounteous collection of species, distributed unevenly into about seventy genera, all of which are strictly marine. Wrasses, as they are known, are largely small to medium size (although some can attain gargantuan proportions), colorful reef associated animals. Their gaudy nature is further accentuated by sexual dichromatism, a product of evolutionary brilliance in the continuous pressure for sex on the reef. Being one of the most speciose families of fish, wrasses have, since their evolutionary arrival onto the scene as we now know, managed to conquer nearly all hospitable habitats and environments. Wrasses can be found in nearly all biotopes, from turbid coastal lagoons to bone crushing mesophotic reefs, and nearly everything else in- between. The family is circumglobal in distribution, with its diversity peaking in the tropics. This is not to say that labrids are absent outside of the equatorial belt. Although labridae diversity diffuses away from this zone, they continue to persist in subtropical and even temperate zones, demonstrating the highly adaptable and successful nature of this family.

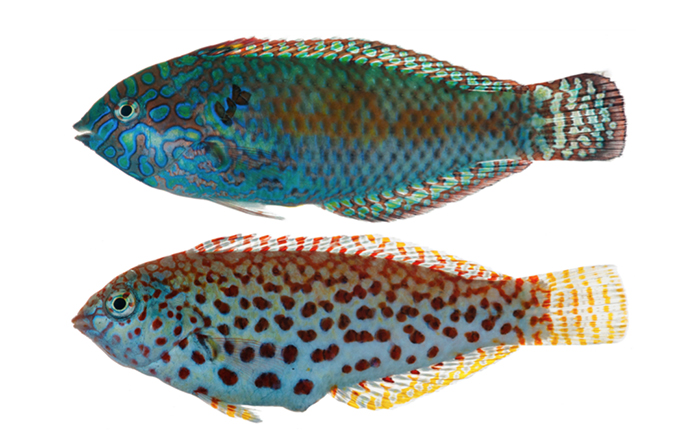

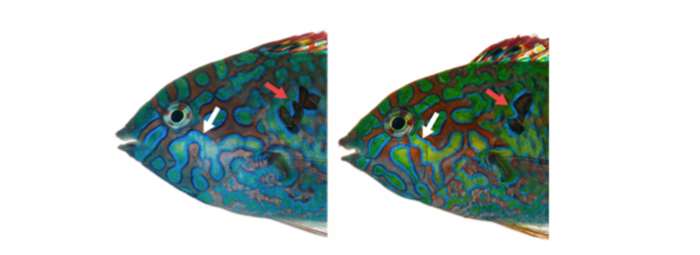

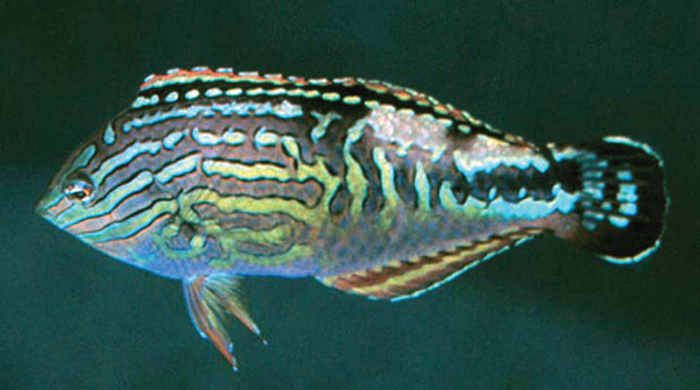

Profile shots of Macropharyngodon bipartitus and M. kuiteri showing the enlarged posterior premaxillary canines. These are often mistaken for their pharyngeal teeth, which are hidden deep in their throats and cannot be seen without an X-radiograph or physical dissection. Photo by Lemon TYK.

From an evolutionary standpoint, wrasses display some of the most outstanding and fascinating evolutionary adaptations of any reef organism. This can be seen in the biology and ecology of the various genera and species within. For example, the universally famous Labroides feed almost exclusively on a diet of ectoparasites. To successfully master their craft, they have, through convergent evolution, adopted the classic blue and white motif to advertise their trade. This, coupled with a unique style of swimming and operation of a cleaning station, has allowed them to diversify and fill a niche that few other wrasses occupy.

Pseudanthias pascalus approaching Labroides dimidiatus to be cleaned. The blue and black motif is a common motif adopted by various cleaning species, and even serves as a model for malicious species that mimic this pattern in order to get closer to their prey. Photo by Lemon TYK.

Evolutionary adaptation can again be seen in the sand-dwelling genus Xyrichthys. Although many other wrasse genera utilize sand burrowing to a certain degree, none do it more masterfully than Xyrichthys, who, very aptly, are also known as cleaver wrasses. These wrasses are very exaggeratedly laterally compressed, allowing them to slice through the sand with ease as they burrow and even swim considerable distances in.

However, of the five hundred or so species, only less than 50% are suitable for the discerning hobbyist, and even less are offered to the aquarium trade with any frequency. Some of the household names like Cirrhilabrus, Paracheilinus, Bodianus and Pseudojuloides are deeply familiar with aquarists, as many of these are colorful, fairly hardy and adequately sized. Another genus that fits these criteria is Macropharyngodon, commonly and colloquially known as the Leopard Wrasses.

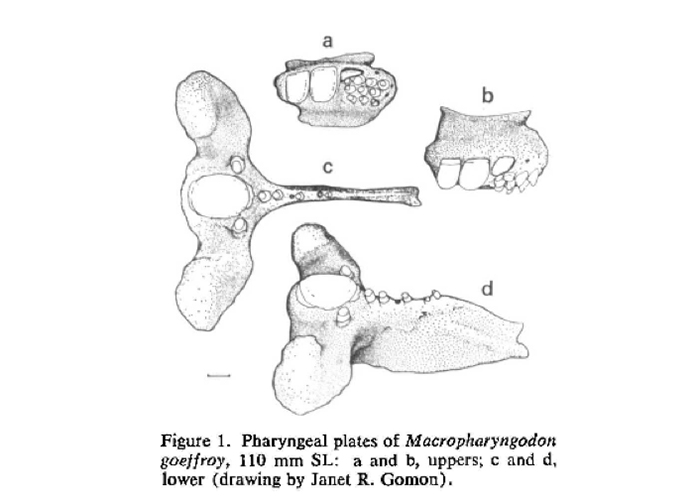

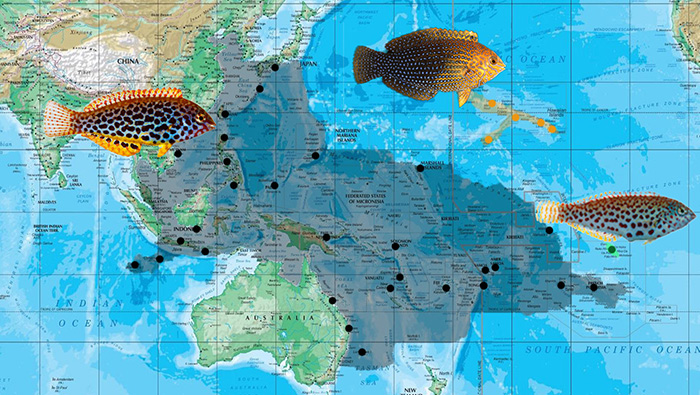

Macropharyngodon is a tropical genus comprising sexually dichromatic reef fishes that are morphologically distinct from all other labrid genera. The eleven or so species are spread out across the Indo-Pacific, but further analysis of the independent clades show a rather classic pattern of allopatric biogeography. The generic epithet “Macropharyngodon” is formed from the amalgamation of the Greek words “makros”, “phárunx (pharynx)” and “odon”, which translate to “big”, “throat” and “teeth”. The epithet is very descriptive, for almost all** Macropharyngodon species possess a single large molariform tooth on the lower pharyngeal plate (flanked by 1 to 3 small blunt conical teeth), and a pair of large canines at the corner of the mouth (Randall, 1978). The latter posterior canines are often mistaken for the pharyngeal teeth, but these are curved and sit on the premaxilla. I have, in the past, confused these for the pharyngeal teeth, but as its name suggests, they are concealed within the throat and are not visible without the use of X-radiographs or dissection.

A diagram showing the molariform pharyngeal tooth on the pharyngeal plates of Macropharyngodon (Randall, 1978).

This unique dentition is used for crushing and grinding shelled invertebrates, which make up a large portion of their prey. Small amphipods, snails, crabs and other benthic creatures are picked up and “chewed”, often repeatedly and methodically. If you’ve kept these fishes, or have seen them in the wild, you’ll notice that most of the “chewing” takes place in the throat, sometimes accompanied by repeated regurgitation until the item is small enough to be swallowed.

Phylogentically, Macropharyngodon is very closely related to Halichoeres. Both are sand dependent, and will burrow into soft substrate to seek refuge from predators, or to sleep. **Although almost all the members in Macropharyngodon are easily identified by their unique dentition, one species straddles the divide between these two genera, and have been the cause of much taxonomic confusion. Halichoeres (Macropharyngodon) lapillus straddles the generic fence, and, in the later part of this article, we will explore why this is so, as well as the features (or lack thereof) that makes this species stand out from the crowd.

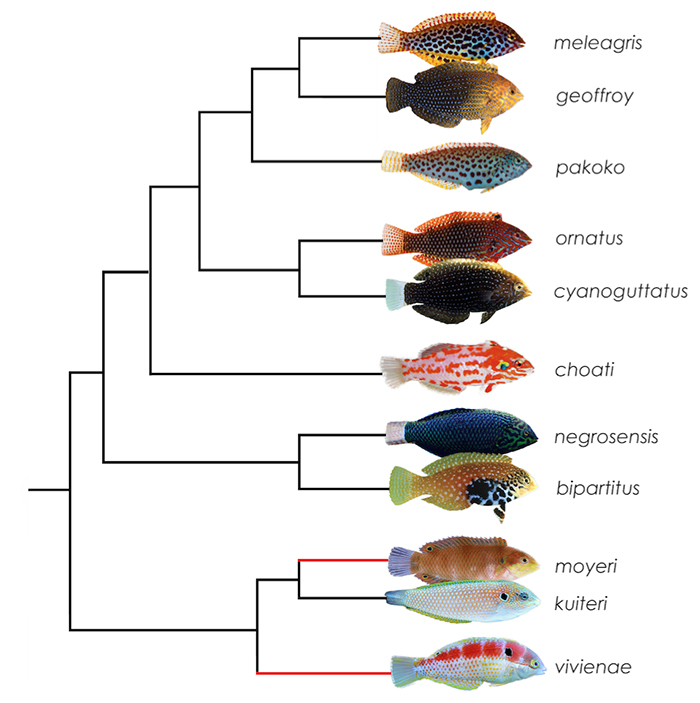

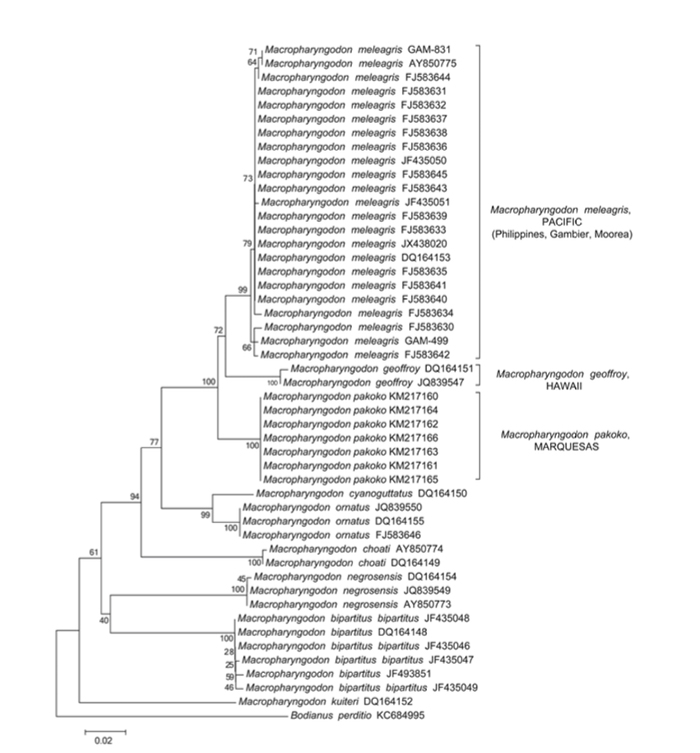

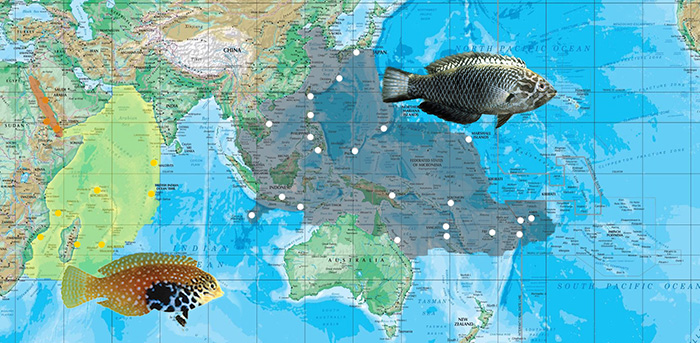

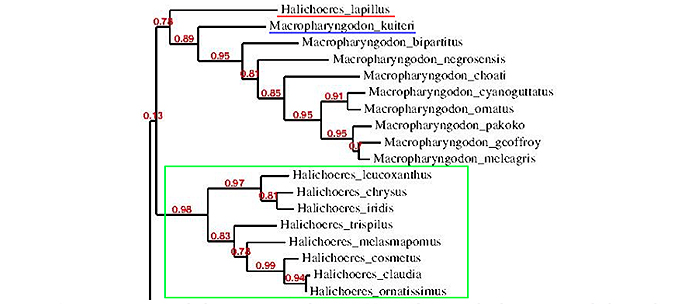

Phylogeny of Macropharyngodon (Trottin et al., 2014) based on CO1, 12S and 16S rRNA mitochondrial sequences. The study does not include moyeri and vivienae, but the two (in red) are predicted to share a clade with kuiteri. Photos of meleagris, pakoko, ornatus by Jeffrey T. Williams; geoffroy, cyanoguttatus, bipartitus by John E. Randall; choati by Hiroyuki Tanaka; moyeri by BSKU, Kochi University and negrosensis, kuiteri, vivienae by Lemon TYK.

In the description of Macropharyngodon pakoko (Trottin et al., 2014), an incomplete phylogenetic tree of the genus was composed based on CO1, 12S and 16S rRNA mitochrondrial sequences. M. marisrubri, M. moyeri and M. vivienae were not included in the study, but based on biogeography and phenotypic characteristics, the latter two (in red) most likely share a clade with M. kuiteri, and it is hypothesized that no genetic differences will be seen in M. marisrubri and bipartitus due to their incipient stages of divergence. The tree reveals the presence of five distinct clades – the meleagris group, the ornatus group, choati, the bipartitus group and the kuiteri group. The following sections herein describes, in more detail, the biogeography and the species within their respective clades. All but one species are available to aquarists.

The Meleagris Group: Macropharyngodon meleagris, geoffroy & pakoko

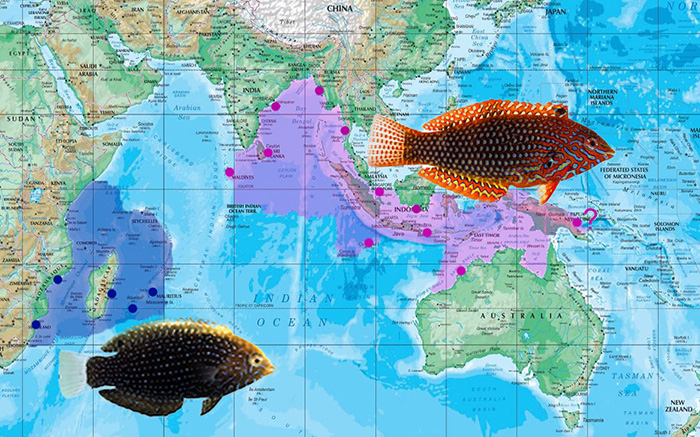

The biogeography of the meleagris group. Photos of meleagris, pakoko by Jeffrey T. Williams; geoffroy by John E. Randall.

The mealagris group comprises three species that are almost wholly Pacific in distribution. The biogeography follows a rather consistent model of allopatricity, with three members occupying disparate regions of the Pacific Ocean. M. meleagris is the most widespread, occurring in the Christmas and Cocos-Islands of the Eastern Indian Ocean, east to the Western Central Pacific, reaching its limit in parts of the French Polynesian Island chain. Interestingly, this widespread species appears to remain unchanged for the most part, retaining its phenotypic integrity over multiple biogeographic regions of endemism. In the Hawaiian and Marquesan Islands, M. meleagris is replaced by M. geoffroy and M. pakoko respectively. Molecular analysis reveals the three to be closely related, with the latter two likely arising from geographical and genetic isolation.

Macropharyngodon meleagris. The females are very characteristically spotted and are truly deserving of their common as well as Latin names. Photo by In-Depth Images Kwajalein.

Males lose the distinct black spots seen in the females. Photo by In-Depth Images Kwajalein.

M. meleagris is the quintessential leopard wrasse, with females displaying a strongly spotted motif. The specific epithet “meleagris” is in reference to the Guinea Fowl, a terrestrial bird sharing the same spotted pattern. Males, on the other hand, lose this distinctive pattern, adopting instead a more homogenous punctuation of green dots. This makes identification rather tricky, as M. ornatus has a male coloration similar to this as well.

M. meleagris is known to hybridize with M. choati in the Great Barrier Reef, but the hybrid is exceedingly rare and likely the only one recorded in the genus.

Macropharyngodon geoffroy, a species endemic to the Hawaiian archipelago south to Johnston’s Atoll. Photo by Lemon TYK.

Macropharyngodon pakoko, male on top, female below. This recently described (2014) species is endemic to the Marquesan Islands. It bears a close resemblance to M. meleagris, but phenotypically, both sexes show noticeable differences. This disparity is further supported by molecular data, which clearly shows the need for a new specific allocation. Photo by Jeffrey T. Williams.

Unsurprisingly, M. meleagris is unable to maintain its Pacific reign in the regions of Hawaii and Marquesas. These two island archipelagos are well known for harboring distinct, endemic fauna, and it is here that many of the ichthyological representatives draw uncanny resemblances to their sister counterparts in the rest of the Pacific. In part, isolation and genetic discontinuity have resulted in the evolution of these endemics, and the representatives of Macropharyngodon here are no different.

M. geoffroy is the sole representative of its genus in Hawaii, where it is readily identified by its roughly bicolor orange and navy body. The usual black spots are metallic cerulean, and are reduced instead, to a fine constellation.

Humeral spot (red arrow) and inverted “U” facial marking (white arrow) in the males of M. pakoko. Photo by Jeffrey T. Williams.

Likewise, Marquesas’ isolated islands have spawned a separate, endemic species. M. pakoko was, before its official description in 2014, known as a cryptic variant of M. meleagris. It differs from the latter by having a black humeral spot outlined in blue, as well as an inverted “U” shaped facial pattern in the males (broken and dashed in meleagris). Females of pakoko are more sparsely spotted than those of meleagris. The specific epithet “pakoko” refers to the famous Marquesan warrior Pakoko, the last chieftain who led the Marquesan resistance to the French during his time. Pakoko is still celebrated in the Marquesas, and is an important figure in the local community (Trottin et al., 2014).

CO1, 12S and 16S rRNA mitochrondrial sequences showing the genetic differences in meleagris, pakoko and geoffroy against the other members of Macropharyngodon. Note the position of pakoko basal to meleagris (Trottin et. al, 2014).

The Ornatus Group: Macropharyngodon ornatus & cyanoguttatus

The biogeography of the ornatus group. Photo of ornatus by Jeffrey T. Williams; cyanoguttatus by John E. Randall.

The ornatus group features a pair of species distributed largely within the Indian Ocean. Like the meleagris group, the members here are allopatric, each occupying disjunct distributions with no contact zones. M. ornatus straddles two sides of the Indian and Pacific Ocean, but only weakly reaching into the Indonesian archipelago. It has been recorded in Papua New Guinea, although this requires further investigation. M. cyanoguttatus, on the other hand, is confined to the African coast and nearby islands of Madagascar, Mauritius and Reunion.

Female M. ornatus. Note the uniform row of spots neatly arranged in neat horizontal stripes. Photo by Lemon TYK.

M. ornatus bears some resemblance to members of the meleagris group, but the spotted pattern on the body is markedly different. In M. ornatus, the spots are rather uniform in size, and are arranged in neat horizontal stripes along the length of the body. This is also seen in M. cyanoguttatus, although its spots are slightly smaller than in the latter species.

The distribution of M. ornatus is nearly parallel to that of Pseudojuloides kaleidos, and its eastern distribution into Indonesia puts it in close proximity with M. meleagris. No hybrids have been documented between the two species, but it is quite likely that it simply hasn’t been discovered yet. Only one hybrid of Macropharyngodon has been documented, and it is between meleagris and choati.

M. ornatus is named in reference to its ornate coloration.

Female Macropharyngodon cyanoguttatus. Note the lineated spot pattern. Photo by Fishwise Pro.

M. cyanoguttatus occupies the Western Indian Ocean, hugging South Africa’s coastline and east to the Mascarene Islands. This region is comprised of two very poorly defined biogeographic regions. Some species appear to encompass both, while others are restricted to either South Africa or the Mascarenes. For example, Pseudojuloides polackorum and edwardi are endemic to the South African coast, straying to Madagascar as their easternmost limit. Further east to Mauritius, they are both replaced by P. xanthomos and P. edwardi respectively. The same can be said for Apolemichthys kingi.

The biogeographical boundaries here, however, do not apply to any of the Macropharyngodon species. M. cyanoguttatus is found throughout this region, and is sympatric with M. bipartitus, M. vivienae and the very mysterious, Halichoers (Macropharyngodon) lapillus.

M. cyanoguttatus is named in reference for its blue spots.

Macropharyngodon choati

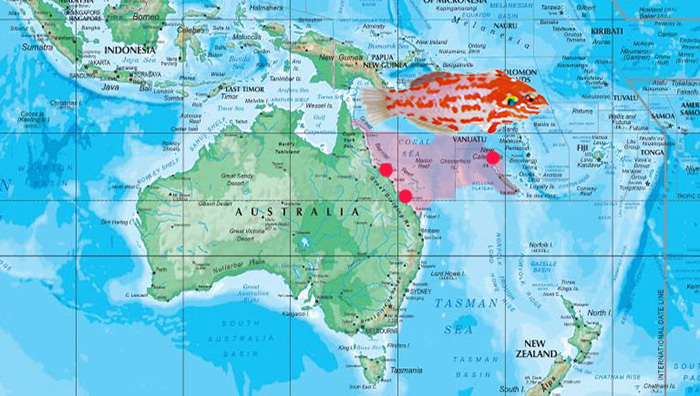

Macropharyngodon choati is endemic to a narrow strip along the East Australian coastline, primarily in the Great Barrier Reef, east to Elizabeth’s Reef and New Caledonia. Photo of choati by Hiroyuki Tanaka.

Macropharyngodon choati is the only representative in its clade, which is unsurprising considering its unique biogeography. The species is endemic to a narrow strip along the East Australian coastline, primarily in the Great Barrier Reef, east to Elizabeth’s Reef and New Caledonia. Like many Australian endemics, M. choati is phenotypically quirky and unique with respect to the other members in its genus.

A young M. choati in captivity. Note the enlarged humeral spot behind the operculum, as well as the pearlescent white ground coloration. Photo by Lemon TYK.

This is perhaps the most decadently colored species, and it cannot be confused with any other of its kind. In the beautiful M. choati, the ground coloration is pearlescent white, with the usual spots in brilliant cadmium orange, modified to form neat rosettes and hieroglyphic like inscriptions. The head is mostly encapsulated in orange, with a prominent black humeral spot behind the operculum. This is a rather unique trait, with only the rather distantly related kuiteri group displaying it with any significant prominence. The species is also the least sexually dichromatic amongst the leopard wrasses, with males and females differing only very slightly in coloration. Males are more extensively orange, with the rosettes conjoining to form small streaks. The cheeks and humeral spot are also lightly tinted in blue.

A male M. choati. Note the extensive orange pattern, the blue humeral spot and the lightly tinted cheeks. Photo by Ameblo.

Hybridization is extremely rare in Macropharyngodon, and, unusually, it is M. choati that forms the only known hybrid (that I am aware of) in the genus. This species is reported to hybridize with M. meleagris in the Great Barrier Reef, and the resulting cross is known from at least two specimens and one photographic record. Because the photo is currently in use for an upcoming manuscript, we are unable to show it, but the hybrid displays a rather even mix of phenotypes from both parents.

The Bipartitus Clade:

Macropharyngodon bipartitus, marisrubri & negrosensis

The biogeography of M. bipartitus and M. negrosensis. Photos of bipartitus, negrosensis by John E. Randall.

The bipartitus clade features two members with very disjunct ranges – one almost wholly Pacific, and the other confined to the Western Indian Ocean. Their similarities on a molecular level are rather unusual, considering the two species are remarkably different in coloration.

A group of female M. bipartitus. Photo by Wikipedia.

M. bipartitus is perhaps rivaled only with M. choati in terms of sheer brilliance. The Latin name means “divided into two”, and this is perhaps in reference to the female’s unique coloration. The females are giddying raspberry red with a clearly delimited black belly, superimposed in a heavy constellation of blue spots and reticulations. It is confined to the Western Indian Ocean, ranging from South Africa to the Mascarene Islands, north to Seychelles, Maldives, Chagos and the Red Sea*.

Male M. bipartitus in the field. Photo by John E. Randall.

The males are extremely different in appearance, representing one of the more dramatic cases of sexual dichromatism displayed in this genus. The difference hasn’t gone unnoticed to ichthyologists, and the sexes were previously described as two separate species – the females as M. varialvus and the males as M. bipartitus. In a 1978 revision of the genus, Randall synonimized the two as M. bipartitus, leaving varialvus as an unaccepted synonym. *M. bipartitus saw a change in taxonomy once again in 2013, when Randall recognized minor differences in the Red Sea population. Based on slight differences in the male coloration, meristics, and biogeography, the Red Sea population was relegated to full species, and was named M. marisrubri – the specific epithet meaning “Red Sea”.

M. marisrubri. Note the apparent difference in spot pattern on the body. Photo by John E. Randall.

M. marisrubri is practically identical to M. bipartitus in its initial and female phase. The males are reported to differ slightly in coloration, with M. marisrubri having a more spotted body pattern. It is widely regarded that the isolation between the Red Sea and the rest of the Western Indian Ocean is responsible for evolutionary divergence in many taxa. In the case of bipartitus and marisrubri, the two are quite clearly in their incipient stages of divergence. Molecular analyses of the two species will likely show negligible or no difference(s) in their sequences, although this will need to be carried out to confirm the hypothesis.

A female M. negrosensis. Note the dark body coloration. Photo by Lemon TYK.

A terminal male M. negrosensis. Note the crosshatched body pattern. Photo by Lemon TYK.

M. negrosensis, as its name suggests, is very dark with only a slight green suffusion in a sidelight. The face is more ornately patterned in a green labyrinth, especially in the males. M. negrosensis has a distribution very similar to that of M. meleagris, but doesn’t reach into the Polynesian Island groups, and only skirts the periphery of Micronesia.

The Kuiteri Group: Macropharyngodon kuiteri, moyeri and vivienae

Biogeography of the kuiteri group. Photo of moyeri by Shigeru Harazaki; vivienae, kuiteri by Lemon TYK.

The kuiteri group is unusual in having members that are slender, pearlescent, and with a very prominent humeral spot behind the operculum. Compared to their congeners, the characteristic spotted pattern is rather reduced here, with M. moyeri going a step further in having all its spots completely removed. These features likely correlate to their basalmost placement in the Macropharyngodon phylogeny, and quite possible represent an ancient lineage more closely related to Halichoeres. In an expanded phylogenetic tree, which includes Halichoeres, these were found to be rather closely related to the iridis and melasmapomus clades of the latter genus, recalling the shared similarities in shape and the prominent humeral spot. This will be discussed in greater detail later on.

A female M. kuiteri. Note the distinct humeral spot and the pearlescent body. Photo by Lemon TYK.

A pair of M. kuiteri, with the male in the background. Note the complete lack of spots in the male. Photo by Lemon TYK.

All three species in this clade have rather small and restricted distributions, with M. kuiteri and M. moyeri being confined to the Pacific, and M. vivienae to the Southern African coast in the Indian Ocean. While Trottin’s phylogenetic study did not include moyeri and vivienae, it could be inferred from their similarities in morphological characteristics and biogeographical patterns that they belong in the same clade with kuiteri. M. kuiteri and M. moyeri occupy a nearly antiequatorial distribution, with the latter having a very restricted range in the Ryukyu Archipelago, south to Taiwan and Northern Philippines. It reaches its distribution limit in Aparri, Cagayan, where it was only recently discovered to occur. Together with M. pakoko and M. geoffroy, M. moyeri has one of the most restricted distributions of any Macropharyngodon, and is likewise the rarest (second only to the unobtainable pakoko) and least encountered species in the trade, with only one specimen being offered from the Northern Philippines.

A male Macropharyngodon moyeri. Note the complete lack of spots. Photo by Shigeru Harazaki.

M. kuiteri enjoys a larger distribution centered around the Melanesian Islands of Vanuatu, Fiji and Tonga. It also occurs along the eastern coast of Australia, extending to Elizabeth’s Reef and New Caledonia.

A female Macropharyngodon vivienae. Note the burgundy dorsum and the fine yellow spots. Also note the enlarged humeral spot. Photo by Lemon TYK.

The third species in this clade is Macropharyngodon vivienae, a beautiful species confined to South Africa’s eastern coast, as well as the Mascarene Islands. This species is a relative new comer to the aquarium industry, debuting only very recently from Kenyan exports. It was later discovered in Mauritius, making this its current easternmost distribution as well as a new range extension for the species.

A male M. vivienae in the field. Note the blue humeral spot and the reddish body hue. Photo by Fishwise Pro.

M. vivienae adopts the usual kuiteri clade appearance. The females are pearlescent with numerous fine yellow spots. The head and dorsum is delimited in burgundy. This species is rare in the aquarium trade, with males being the rarer sex. Like in M. kuiteri and M. moyeri, the spots tend to fade with age, and the humeral spot takes on a blue edged appearance.

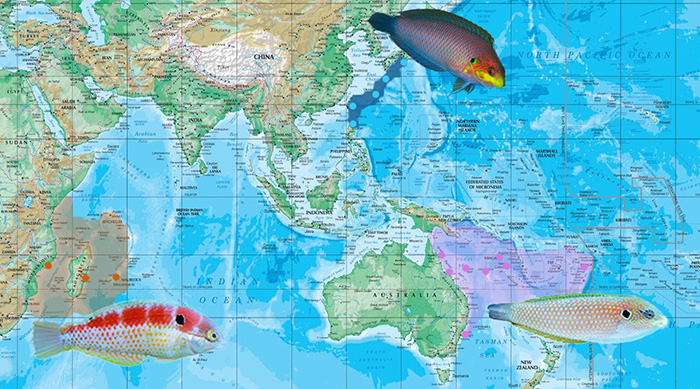

A more extensive phylogenetic tree showing Macropharyngodon being the sister clade to Halichoeres (in green). Note the basal position of the kuiteri group (in blue), and the lapillus as the basalmost branch (in red). Phylogenic tree was constructed using genbank data by Joe Rowlett.

An expanded phylogenetic tree reveals that Macropharyngodon is the sister clade to Halichoeres. The basalmost branch in the Macropharyngodon phylogeny is occupied not by the kuiteri clade, but by one species, and it is, perhaps, the most mysterious and enigmatic of all – Halichoeres (Macropharyngodon) lapillus. This brings us to our final chapter in this article.

Halichoeres (Macropharyngodon) lapillus: A Case of Mything Teeth (1)

The biogeography of Halichoeres (Macropharyngodon) lapillus. It is confined to the Western Indian Ocean, occupying the East African coast up to Oman, and east to Seychelles and the Mascarene Islands. Photo by Lemon TYK.

This ornate species has been the subject of some taxonomic debate amongst wrasse aficionados. Despite looking remarkably similar to Macropharyngodon, it was described in 1947 as Halichoeres lapillus. Randall later revised Macropharyngodon in 1978, but failed to find any of the diagnostic pharyngeal teeth in H. lapillus. The species therefore remained in Halichoeres based on this missing trait. Throughout the course of time, many authors and enthusiasts have noted the uncanny resemblance that H. lapillus has towards Macropharyngodon, so much so that it, in various literatures, has been moved unofficially to the latter genus. Rudie Kuiter’s book on wrasses, for example, removes lapillus from Halichoeres, placing it well in Macropharyngodon instead.

It is crucial to note that despite this taxonomic limbo, none of the changes made were official or formal, and lapillus still remains in Halichoeres. Although the species lacks the usual pharyngeal teeth associated with the genus, its mitochondrial CO1 sequence shows that lapillus is more closely related to Macropharyngodon, being the basalmost member of the genus.

Macropharyngodon lapillus. Photo by Lemon TYK.

This suggests that Halichoeres lapillus may perhaps represent an ancient lineage of leopard wrasses, and its basalmost placement in the tree could explain the weak or absent pharyngeal teeth. In essence, it forms a link between Halicheores and Macropharyngodon. The bigger question is where does it belong? Seeing that its placement in both genera is equivocal at best, it would be interesting to reexamine the pharyngeal plate of the species to see if there are any minute vestigial signs of teeth development. Alas, this conundrum is better left to taxonomists. For now, Halichoeres (Macropharyngodon) lapillus will straddle the fence, unbothered by its mything teeth.

References

Gill. A.C., 2015. A case of mything teeth: on the presence of vomerine and palatine teeth in the Pomacanthidae (Teleostei). Zootaxa 3994 (4): 593-596.

Trottin. E.D., Williams J.T., Planes S., 2014. Macropharyngodon pakoko, a new species of wrasse (Teleostei: Labridae) endemic to the Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia. Zootaxa 3857 (3): 433-433.

Randall, J.E., 1978. A revision of the Indo-Pacific labrid fish genus Macropharyngodon, with description of five new species. Bull. Mar. Sci. 28(4):742-770.

0 Comments