By Todd Gardner

The caringidae is a family of tropical and warm-temperate, marine fishes found in warm seas throughout the world. Commonly known as jacks, the carangids display a wide range of body shapes, from the standard fusiform (the quintessential “fish” shape) seen in the amberjacks, to extremely deep-bodied, compressed forms exemplified by the lookdowns. Common characteristics of carangids include small, silvery cycloid scales, a well-developed lateral line, a narrow caudal peduncle and a widely forked or lunate caudal fin. Scales along the lateral line, especially on the caudal peduncle, are often modified into sharp scutes. Jacks typically have two dorsal fins with 3-9 spines in the anterior, and one spine, followed by 18-37 soft rays in the posterior. Usually, the first two of three anal fin spines are separate from the rest of the fin, which has 15-31 soft rays. In some species there are several detached finlets posterior to the dorsal and anal fins. To summarize carangid morphology, you could say that they are built for rapid and long-distance swimming. All members of the family are predators. Most feed in the water column above reef habitats or in the open ocean. Some, most notably Trachinotus spp. Sift through sand for their invertebrate prey.

The carangids that are found in the waters of New York can be placed into one of three categories based on their ecological role here: Transients, those that migrate into, and back out of our area; strays, those that are spawned in a warmer climate and carried here as eggs or larvae, only to die at the onset of winter; and temporary residents that use temperate coastal waters as a nursery. Unfortunately, for most species, there is insufficient data available to appropriately categorize them.

Ironically, despite the fact that there are no resident carangids in the northeastern US, they are the single most represented fish family that occurs here. There are at least 16 species of jacks that can be found regularly in the inshore waters of New York. Most carangids are only encountered here as juveniles in the summer and fall. These are often caught in seine nets by fish collectors in search of bait or tropical reef fishes. Some species, like the scad and crevalle jack are easily overlooked as there is nothing particularly memorable about their appearance and they easily disappear into a net full of bait fish. On the other end of the spectrum are the lookdown and African pompano. With their extremely deep bodies and long fin-ray extensions these species stand out as exotic, even to the most casual observer. The voracious feeding habits and rapid growth rate of jacks means that by the end of their short season here, many of them are large enough to be hooked by anglers, especially while fishing for snappers (the local name for juvenile Pomatomus saltatrix).

As a general rule, jacks are pelagic predators and therefore, are completely unsuitable for the home aquarium. Unless you have a very large tank (thousands of gallons), or a good relationship with the staff at a public aquarium that will take them off your hands, you should probably resist taking jacks home with you. Even smaller species like lookdowns and scad that can be housed in a 200-300 gallon tank, don’t really thrive as adults unless they are in large schools with a lot of open space. Nevertheless, fish collectors, myself included, often encounter carangids during our excursions and they can be difficult to resist taking home. Unfortunately, local field guides don’t often include a comprehensive listing of these warm-water species or photos of their small juvenile stages that are most often encountered here.

The Jacks of New York: Caranx hippos

The crevalle jack is a large, deep-bodied jack with a steep forehead and a prominent black spot on the edge of the opercle (lacking in small juveniles). Scales are absent from much of the chest. Small juveniles often display a black banded pattern that can quickly fade. Adults can reach a length of 1.5m. In New York, C. hippos have been collected from virtually all marine habitats, from the open ocean, to deep within the Long Island Sound and the Hudson River. This is one of the most commonly-encountered jacks in our area and the only species for which there is documented evidence for young-of-year individuals returning to the reproductive population south of Cape Hatteras.

Caranx hippos, crevalle jack.

Caranx latus

The horseye jack is very similar in appearance to the crevalle jack, especially as a small juvenile. For this reason, it is probably under-reported in New York waters. The front of the head is slightly less steep in C. latus and the black spot at the edge of the opercle is smaller. Adults are more easily distinguished from C. hippos as their entire chest is scaled and the scutes, especially those along the caudal peduncle, are usually dark. C. latus grows to about 75cm in length. This is a relatively common jack in most marine waters of New York.

Caranx latus, horseye jack.

Caranx crysos

The blue runner is a medium-sized, elongate jack that is highly variable in color – typically yellowish, olive or bluish above and silvery below. Banding in juveniles persists in sub-adults, but is usually less prominent in juveniles than in similar species. C. crysos occurs in New York with less regularity than the previous two species, but at times they can be found in large schools around buoys and other structures. C. crysos is easily distinguished from C. hippos and C. latus as it is noticeably more elongate and the forehead is much less steep than in other Caranx spp. found here.

Caranx bartholomaei

The yellow jack is an uncommon stray in the northeastern United States. C. bartholomaei exhibit a yellowish body and yellow axial fins, and reach a length of 1m. Juveniles have pale, irregularly shaped spots covering much of the body. This is the only member of the genus with a juvenile that is spotted rather than barred. Yellow jacks can be found along jetties and in eelgrass beds in bays that connect directly to the Atlantic Ocean.

Caranx bartholomaei, yellow jack.

Seriola spp.

Jacks of the genus Seriola are collectively called the amberjacks. Compared to Caranx spp., they are more elongate with a more pointed snout, and typically have a dark diagonal line through the eye that persists into adulthood. The caudal peduncle is lined with a fleshy keel rather than sharp scutes. Although all four species of Seriola from the Western North Atlantic can be found in New York, the banded rudderfish, S. zonata is, by far, the most common in our inshore waters. All members of the genus have banded young, however the banded rudderfish is distinguished by six very bold black bands on a silvery-grey background. S. zonata can be confused with the greater amberjack, S. dumerili, which has a similarly banded juvenile. The body of S. zonata is more elongate and the base of the anal fin is shorter. All Seriola spp. can be found around buoys and pilings as juveniles, especially if there is a strong current. Adults of S. dumerili, the largest species, are occasionally caught by rod-and-reel fishermen along jetties of Long Island’s South Shore. The lesser amberjack, Seriola fasciata, and almaco jack, S. rivoliana are the other two species found here, but uncertainty in their identification in many reports makes it difficult to gage their relative abundance.

Seriola zonata, banded rudderfish.

Seriola dumerili, Greater Amberjack.

Trachinotus spp.

The genus Trachinotus consists of what are commonly called the pompanos. Three species occur in our area: T. falcatus (permit), T. carolinus (Florida pompano), and T. goodei (palometa). Of these, only T. falcatus is considered common. The permit is a deep-bodied, silvery jack with pointed, elongate anterior lobes on the dorsal and anal fins. It lacks the keels and scutes that are common in the caudal peduncles of other carangids. In lateral view, the body is essentially diamond shaped. The sloping forehead terminates in a blunt snout. Small juvenile permits are often black or reddish, but can rapidly change color to the more characteristic silver. In young individuals, the pelvic fins and front lobe of the anal fin are bright orange (vs. yellow or pale in T. carolinus and T. goodei). T. falcatus is the largest member of the genus in the Western Atlantic, reaching a length of 114cm. The four narrow bars that make T. goodei easy to recognize as an adult are not seen in small juveniles.

Trachinotus falcatus, permit (small juvenile).

Trachinotus falcatus, permit (small juvenile).

Trachinotus falcatus, permit.

Selene vomer

The lookdown, with its extremely deep, compressed body, and steep forehead cannot easily be confused with any other fish. The skin is silvery and iridescent with brassy highlights. The anterior lobes of the soft dorsal and anal fins are extremely long in adults. Juveniles often have gold or brown bands. Pelvic fin rays and first two dorsal spines in small juveniles are very long and ribbon-like. Caudal peduncle is narrow with scutes forming a keel. Young are common in the south shore bays of Long Island and other coastal areas in the northeastern US. Late in the season, larger individuals have been observed in schools. These are likely young-of-year. S. vomer is popular in the aquarium trade and is highly sought after by local fish collectors.

Selene vomer, lookdown.

Selene setapinnus

The moonfish is similar to the lookdown, but more elongate and lacking the gold banding, long lobes on dorsal and anal fins, and ribbon-like rays on dorsal and pelvic fins. Juveniles have a black spot on the center of each side. Occasionally, large schools of S. setapinnis are encountered in nearshore ocean waters, bays and the Long Island Sound.

Selene setapinnus, moonfish.

Alectis ciliaris

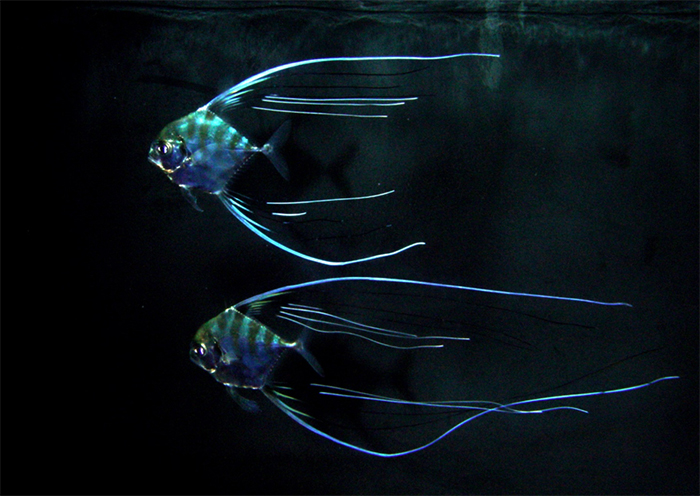

The African pompano is one of three species in the genus Alectis and the only representative in this part of the world. It has a steep rounded forehead and the posterior half of the body is triangular. Long filaments trail from the soft dorsal and anal fin rays, particularly in juveniles in which the filaments can be several times the body length. As in Selene spp., adults are more elongate than young. The African pompano reaches a length of 1.5m and is an important food and game fish.

Alectis ciliaris, African pompano.

Alectis ciliaris, African pompano.

Selar crumenophthalmus

Scads are small, elongate jacks that form enormous schools in nearshore and offshore waters throughout the world. They feed on zooplankton and are an important food source for low and mid-level predators. The bigeye scad is one of at least three species encountered regularly in New York. Small juveniles are often found in bays, around docks and jetties, or drifting under Sargassum weed and other flotsam at sea. Adults are more common offshore. Other scads in our area include Decapterus punctatus and D. macarellus.

Selar crumenophthalmus, bigeye scad.

Consisting of 146 species in 30 genera, the jacks are enjoyed by recreational fishermen, divers, and consumers of seafood throughout the world. They are considered one of the most commercially-important families of fishes world-wide. While we are only graced with their presence seasonally here in New York, they contribute significantly to our marine biodiversity. Despite their prominent position as the most speciose family of fishes in New York, their ecological role here, as well as the role of this region in the life history for most species remains poorly understood. The presence of warm-water fishes so far from the tropics is commonly the result of larval transport out of the reproductive population by ocean currents (The Gulf Stream in this case), however, it seems likely that some carangid species in this part of the Atlantic may be in the process of a range extension, at least in terms of their exploitation of nutrient-rich, temperate coastal waters as nursery grounds. Whatever is actually going on here, one thing is certain: Research opportunities abound for budding fisheries biologists willing to tackle the jacks of New York.

0 Comments