Marine biologists and climate scientists have started using the term ‘blue carbon’ to describe the amount of carbon that is locked up in marine ecosystems. One of the most effective ecosystems for removing carbon (in the form of CO2) from the atmosphere via the oceans is seagrass meadows.

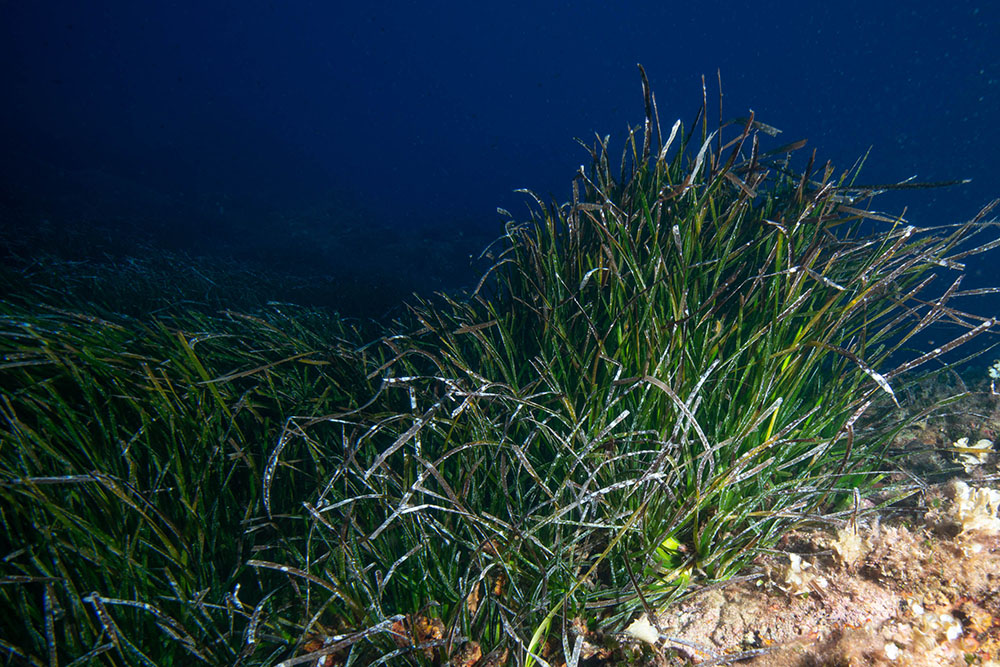

I’ve become quite fascinated by seagrass; any true plant that has adapted to life in salt water is going against the trend somewhat. Here’s a series of images of Posidonia oceanica, the dominant seagrass species in the Mediterranean.

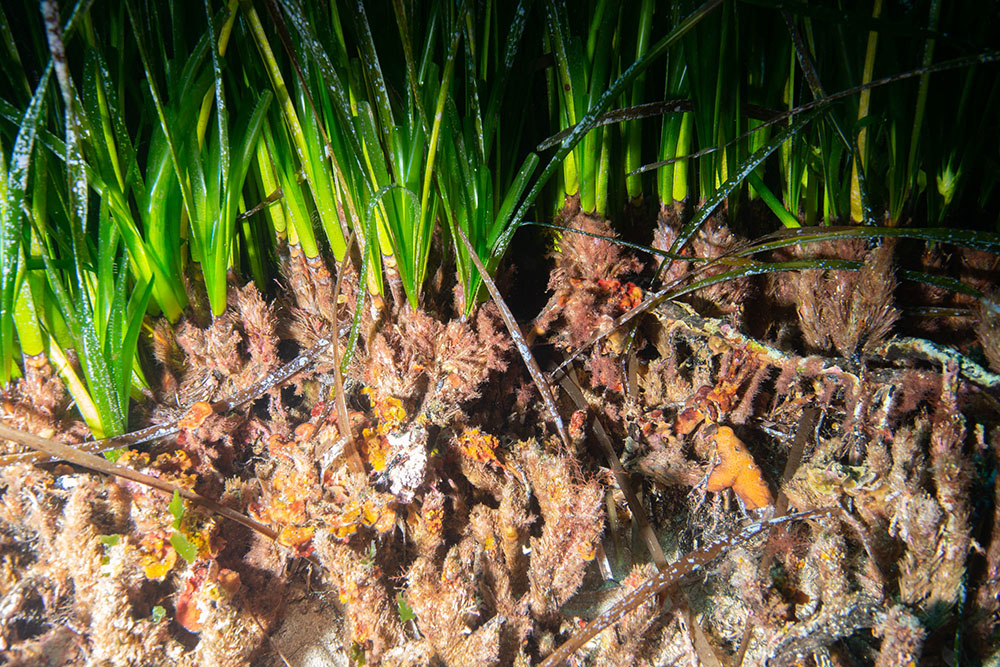

Along with mangrove forests and estuarine mud flats, seagrass meadows play a vital role in calculating carbon budgets. Scientists have discovered that Posidonia meadows sequester more carbon per unit area than terrestrial forests. Over time, leaf and root material builds up, in anoxic conditions, to create something akin to peat. These deposits can be many meters deep and have been building for centuries, if not millennia. Some estimates suggest that areas of Posidonia could be tens of thousands of years old.

Not only are seagrass meadows useful for absorbing CO2, but they perform many other functions, from coastal protection to provision of a nursey habitat for fish and invertebrates. Dead leaf material washed ashore also helps prevent beach erosion and to a certain extent adds nutrients and biological material to near-shore habitats.

Pollution, agricultural runoff, and physical damage from unregulated boat mooring pose significant threats to Posidonia habitats and the species they support, and of course, any physical damage will allow oxygen to get to the ‘marine peat’ thus releasing carbon.

Pinna nobilis. sadly this species which can reach a metre in length is facing extinction from disease

Happily, the value of Posidonia is being recognised amongst policy makers, who are beginning to protect this important part of our ecosystem.

0 Comments