The early eighteenth century roughly marks the starting point for the science of coral reef biology, and a key figure from this period was a Dutch apothecary named Albertus Seba. Unlike other notable biologists of his day, Seba was an amateur, and his study of marine organisms was at least partly motivated by the hope of finding new pharmacological substances and partly from the desire to impress others with the vastness of his acquisitions.

Amsterdam was a major international port in those days, and traders from the Dutch East India Company arrived regularly from the islands of Indonesia. These lands had only recently been colonized, and the tropical flora and fauna found here was always in demand among European collectors. So, along with their lucrative spices, merchants brought back a variety of exotic creatures, which aspiring naturalists like Seba were all too eager to snatch up.

Seba’s “cabinet of natural curiosities” shone above all others, containing drawer after drawer of priceless specimens—thousands upon thousands of plants and insects and reptiles and snails and corals, etc, etc, etc. In 1716, Peter the Great was so impressed that he purchased the collection in its entirety to furnish Russia’s first museum, the Kunstkamera. This allowed Seba to start anew, and he quickly assembled an equally impressive assortment which attracted many of the leading zoological minds across Europe.

It was this second collection that Seba would have published into a four-volume series known as the Thesaurus. This was a monumental effort, the likes of which had never before been attempted at such a grand scale. The first volume appeared in 1734 and covered everything from plants and mammals to birds and reptiles. It was followed up with a second volume in 1735 devoted primarily to snakes, a favorite of Seba’s.

Peter Artedi, the “father of ichthyology”, came to Amsterdam that year to catalogue Seba’s specimens, and it was here that he tragically drowned in one of the city’s canals at just 29 years old. Artedi’s name is not as widely known these days as it should be, but it was his ichthyological work which largely informed the classification scheme created by his colleague, Carolus Linnaeus. He too would visit Seba in Amsterdam, and several of the specimens in this collection would be used as holotypes in Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae, first published in 1735.

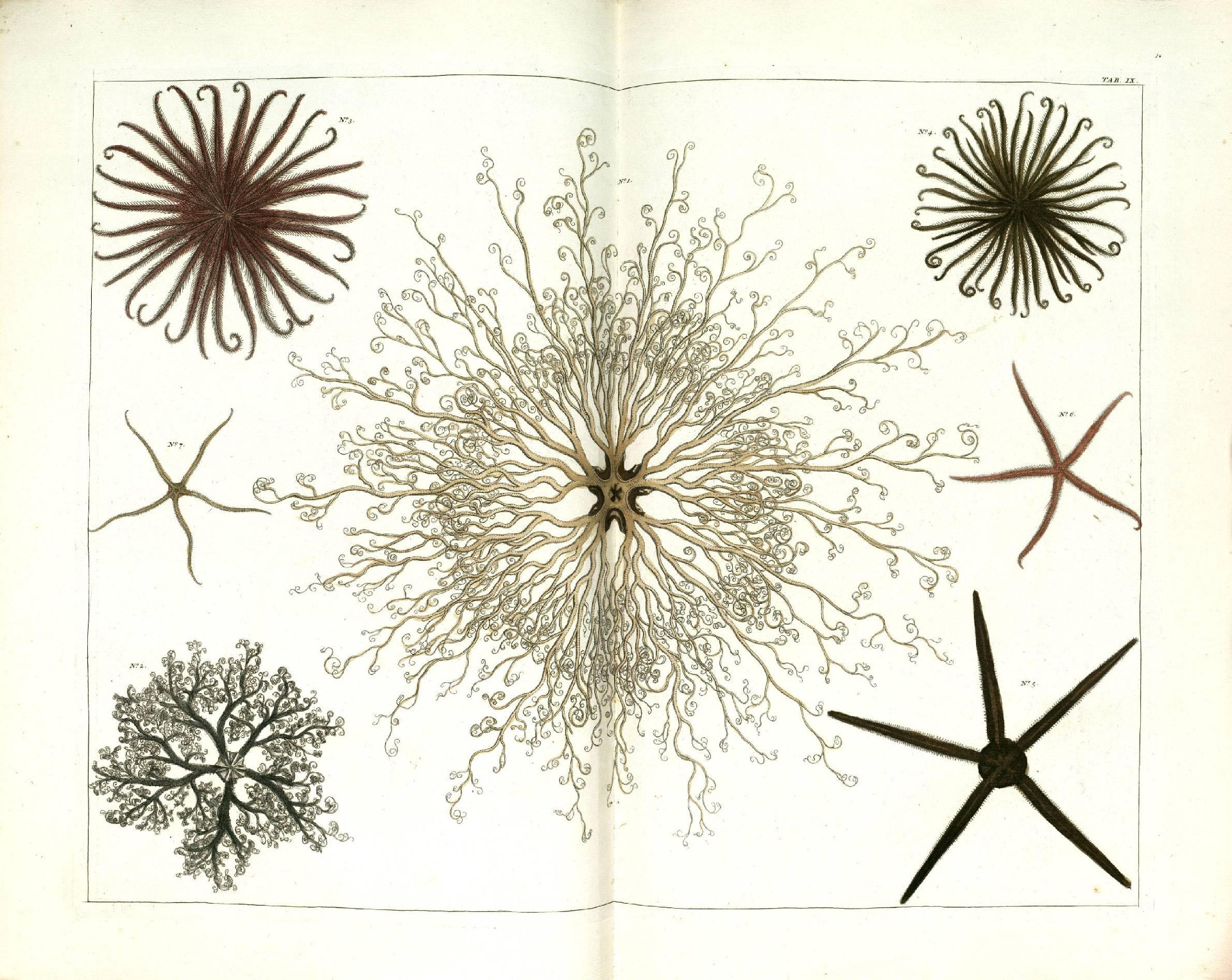

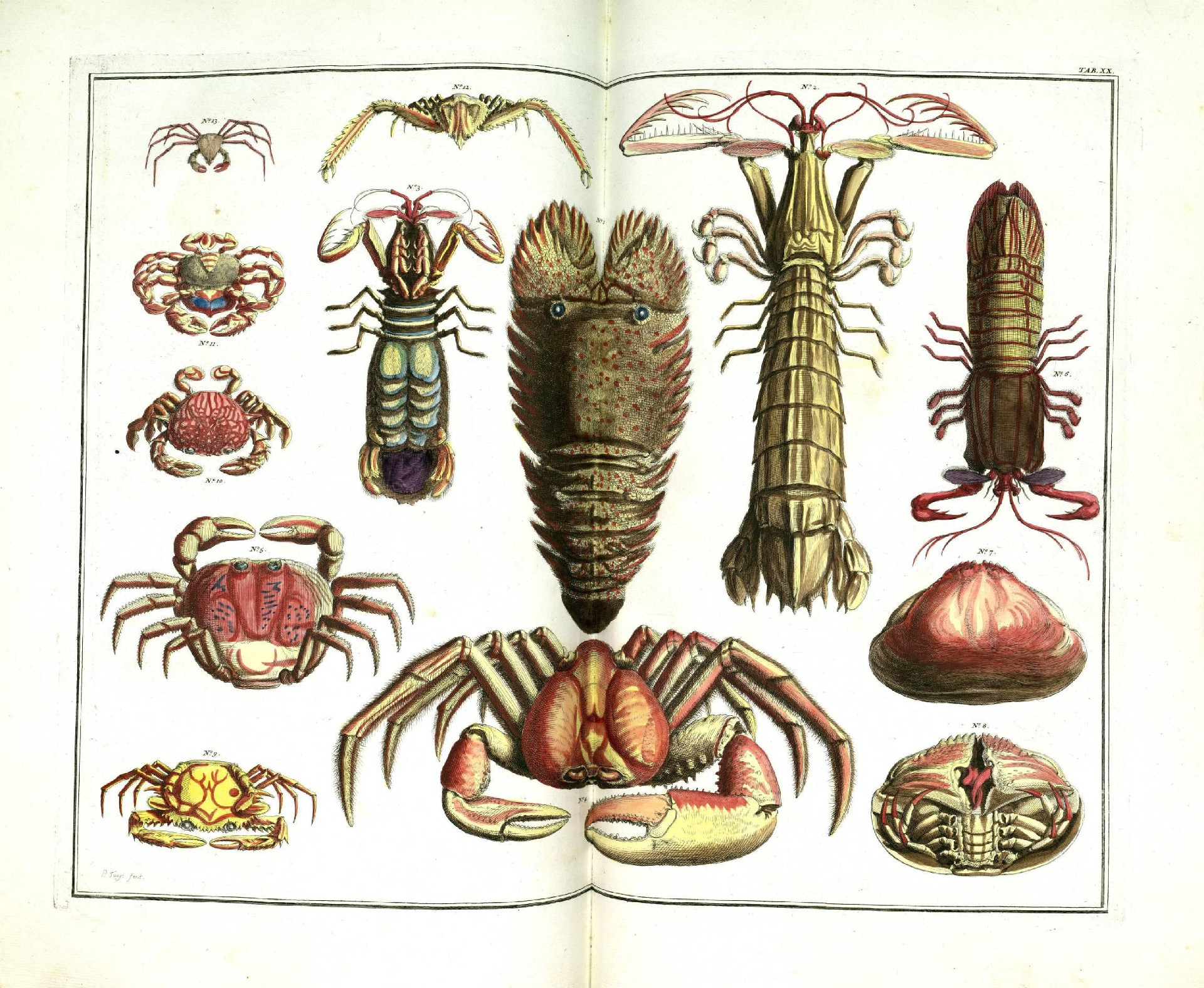

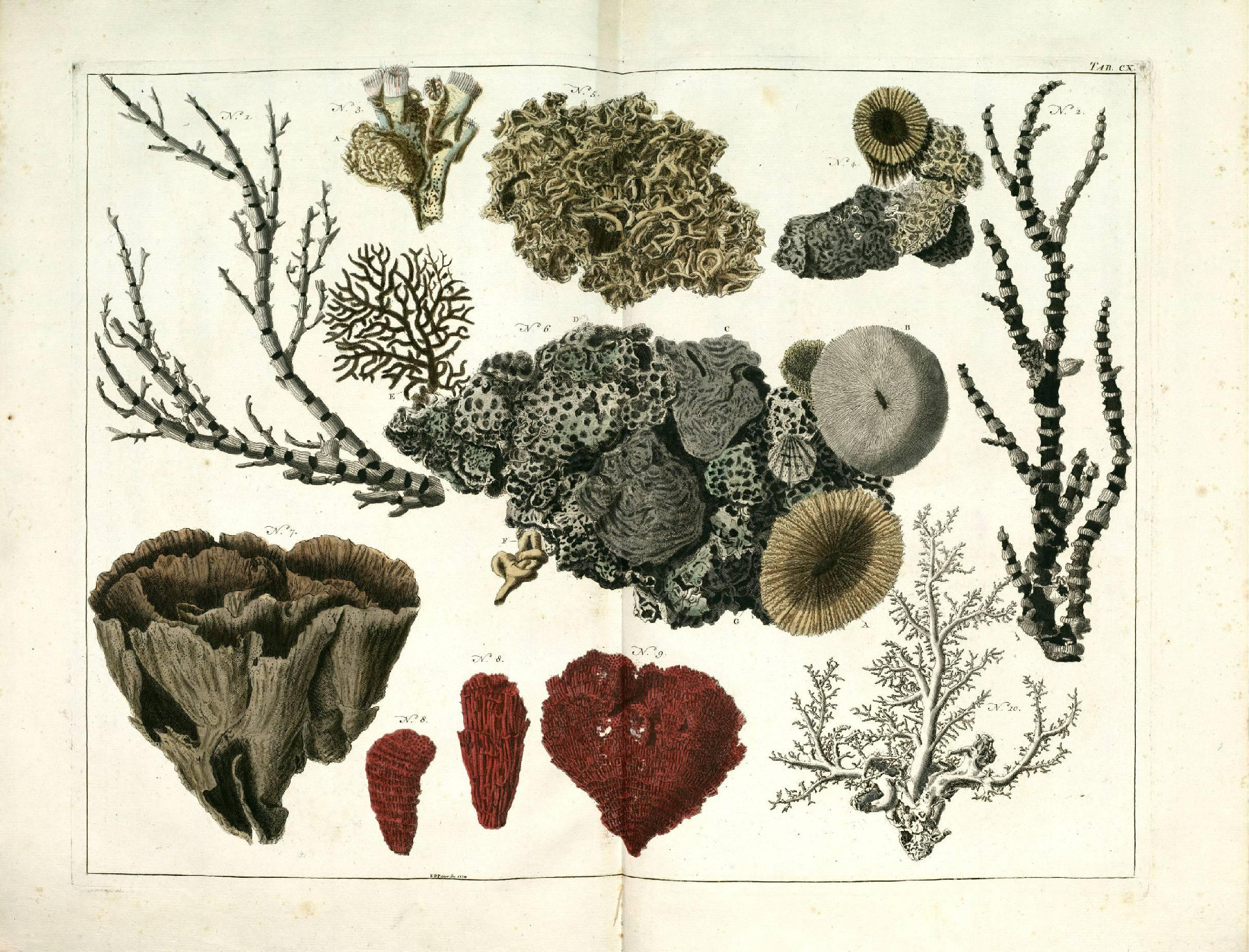

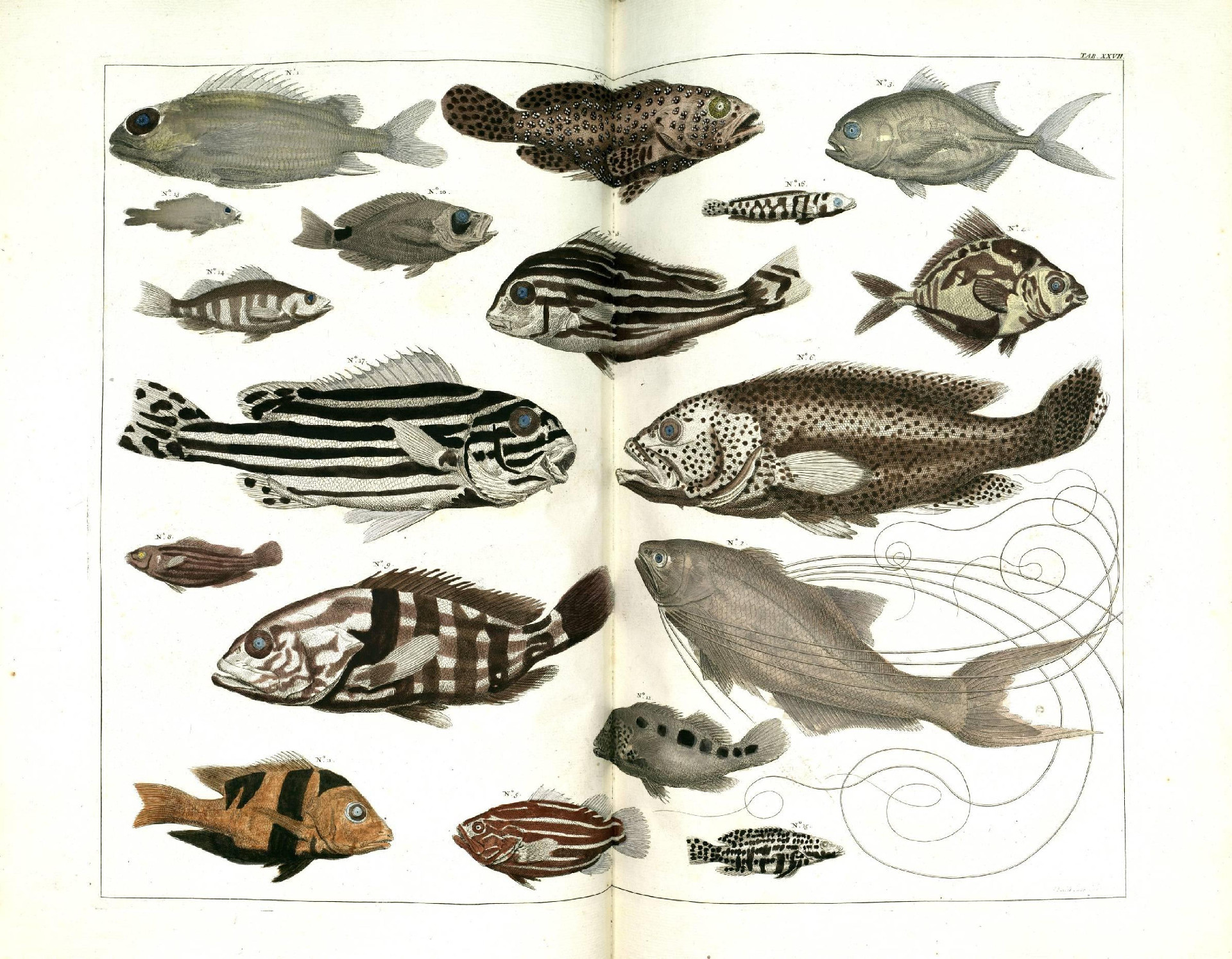

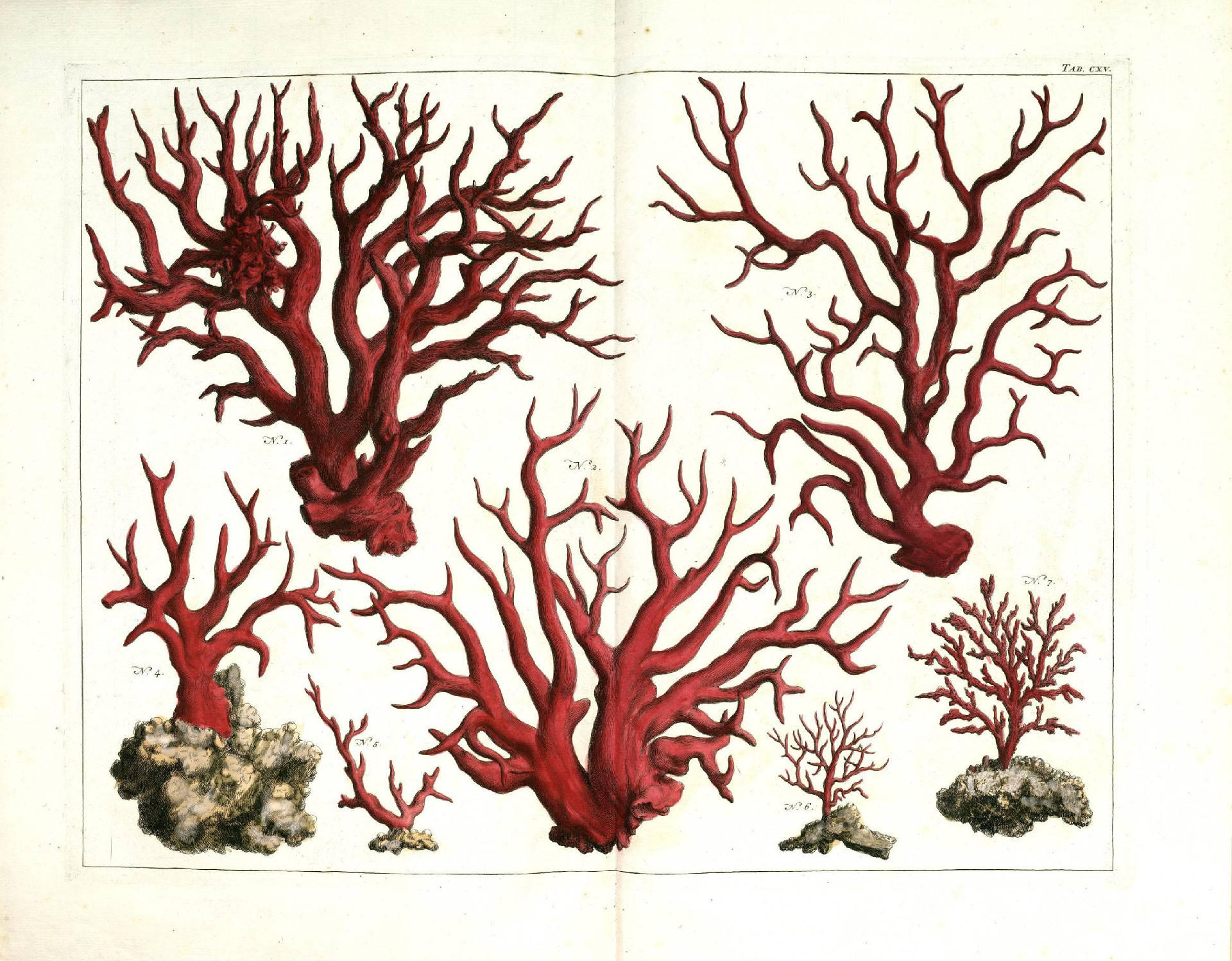

Sadly, Seba would not live to see the publication of any further volumes in his natural history magnum opus, dying in 1736 at the age of 70. After his death, the collection had to be auctioned off in pieces to finance the completion of his project, and, in 1759, the world was treated to Volume 3, which covered a variety of marine invertebrates and fishes, followed by Volume 4 in 1765, which featured insects and minerals.

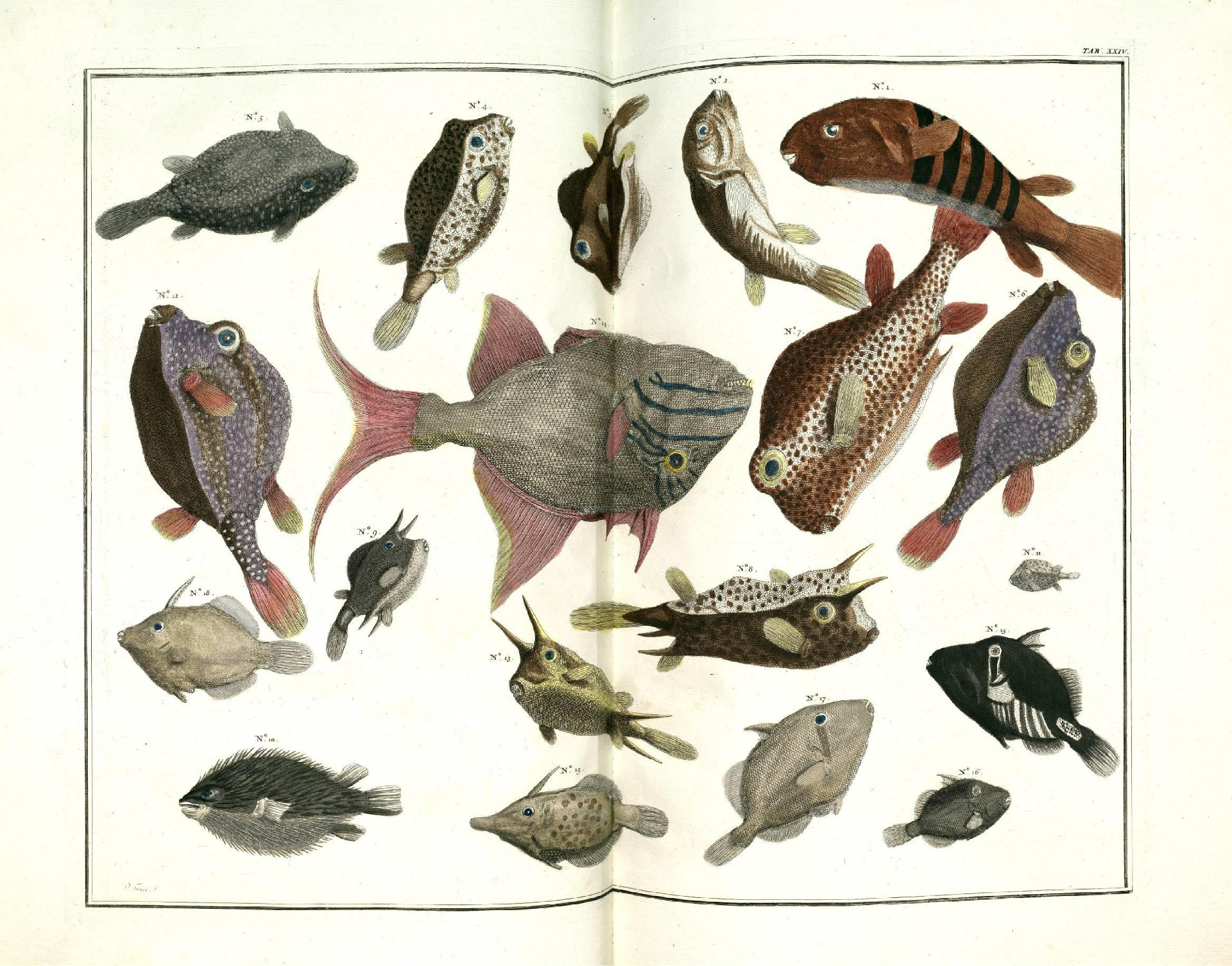

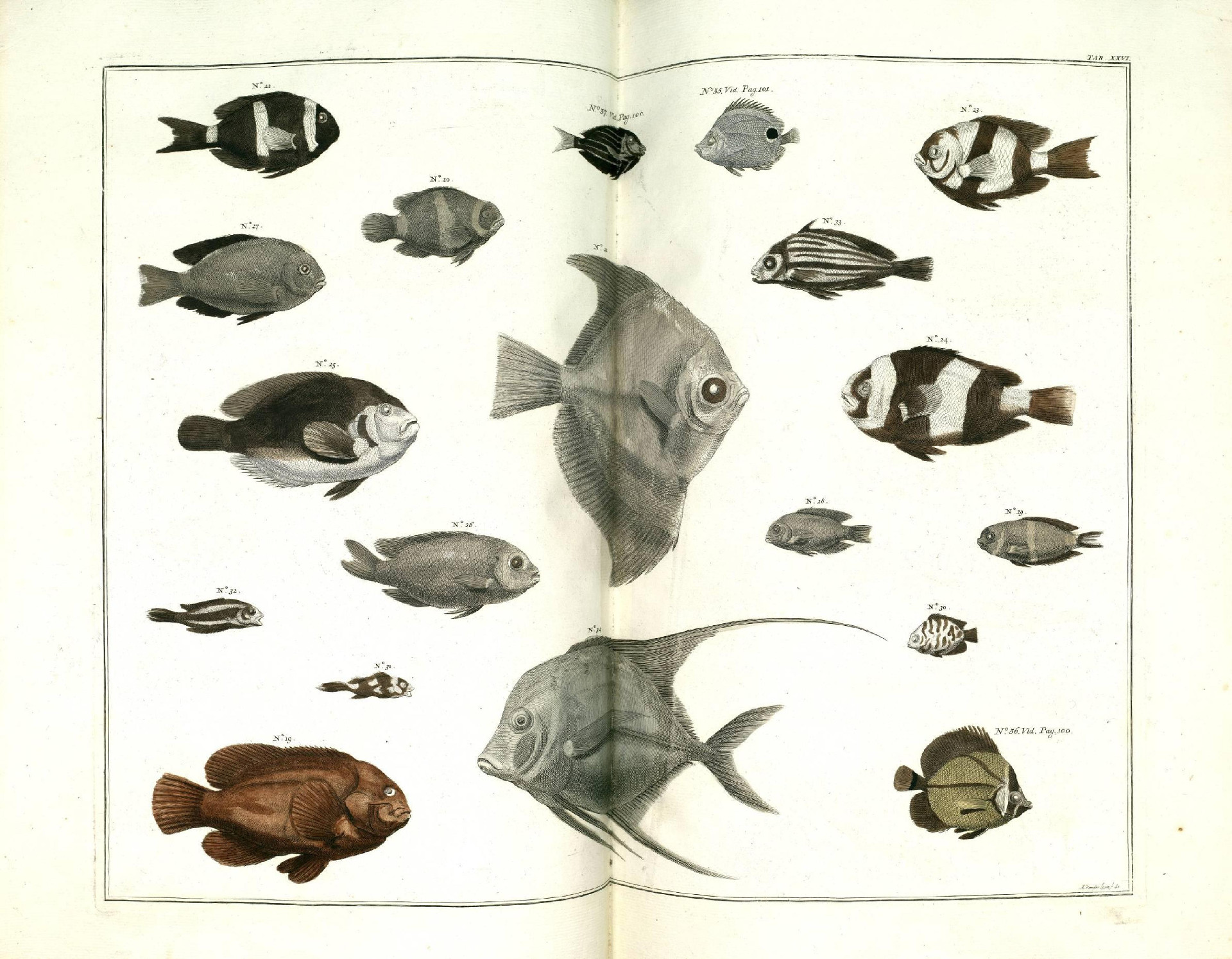

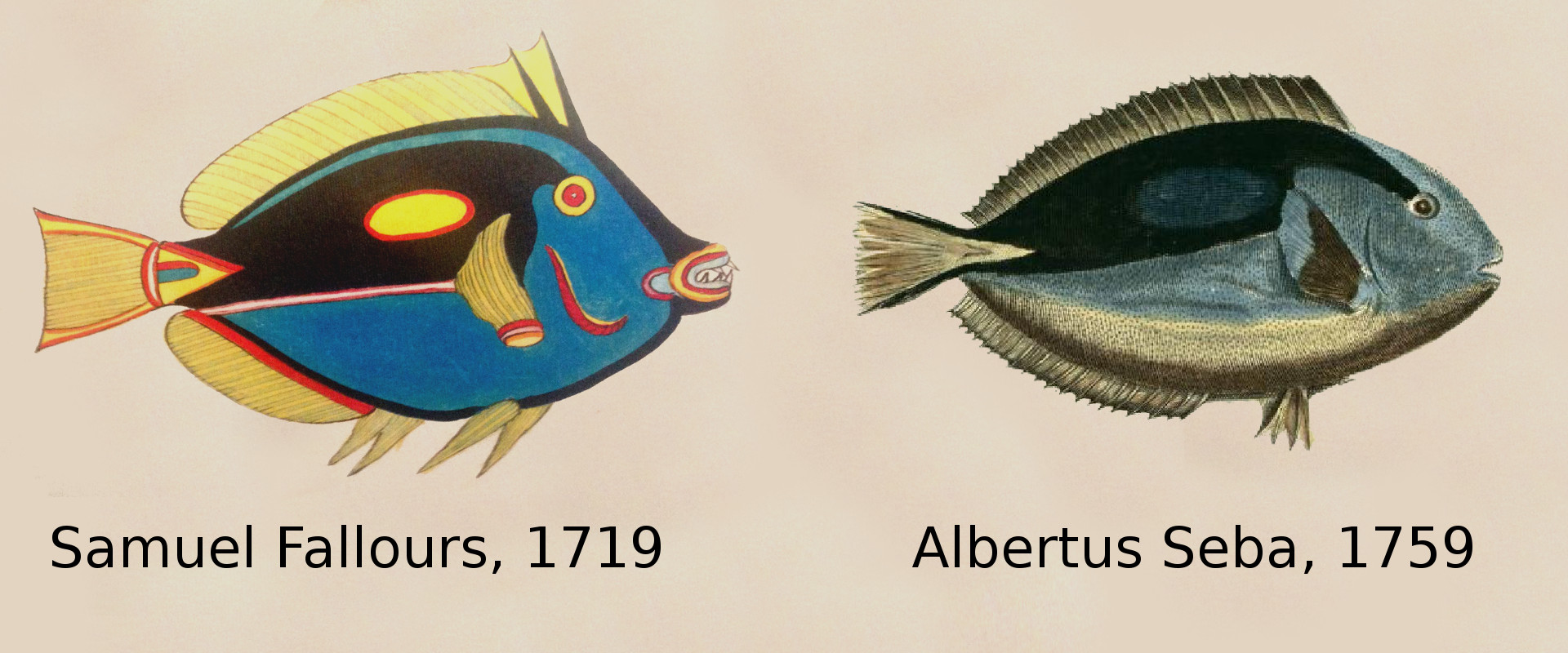

When the Thesaurus was finally completed, it contained a remarkable 446 plates which illustrated thousands of specimens, most of which would have not previously appeared in print. As this work largely predates Linnaeus’ taxonomic treatise, there are no scientific names accompanying the text. But the illustrations are for the most part so beautifully and accurately drawn that there is generally no trouble identifying the species discussed. The quality of this work is especially evident when compared against the only other major publication of this type that predates it, Samuel Fallours’ “Fishes, Crayfishes and Crabs…” from 1719.

Fallours is rightly credited with producing the first color illustrations of Pacific marinelife, but his idiosyncratic drawing technique is so highly stylized as to be cartoonish. Compare his illustration of a Pacific Blue Tang, with its imaginative colors, bizarre proportions and menacing rictus, to that from Seba’s Thesaurus, which looks as though it might swim right off the page. Few written works on natural history from this early period come anywhere close to this level of verisimilitude, and the credit must largely go to the lead illustrator, Peter Tanje, and his collaborators. As a work of natural history art, Seba’s Thesaurus is without equal. A full set that went to auction at Christie’s back in 2000 sold for $442,500, but, if you’re willing to settle for a reproduction, Taschen has a more modestly priced facsimile which no doubt would look quite nice on a coffeetable.

But Seba’s true legacy is as a pioneering naturalist and a keen observer of the animal kingdom. His specimens sit in museums around the world, oftentimes as holotypes for well-known species. And while your average aquarist is unlikely to be familiar with Albertus Seba, most will have heard of the aquatic organisms named in his honor—the Sebae Anemonefish (Amphiprion sebae), the African Mono (Monodactylus sebae), and the Sebae Anemone (Heteractis crispa).

0 Comments