The history of Amphiprion frenatus reproduction in Jesolo

When some members of the Aquarist team at Jesolo Sea Life noticed that two Amphiprion frenatus became particularly territorial, they started to keep an eye on them. The couple soon cleaned the internal part of a decorative ceramic to lay eggs on it!

When the tiny larvae inside the eggs started showing distinctive eye spots (8 days after laying, more or less) the ceramic was moved to a smaller tank containing the same water of the original tank. It was very good luck that the eggs were laid on a removable element!

The rearing tank was without filter, and was maintained with a 20% daily water change with water from the main system. The tank was siphoned regularly with a very tight pipe to remove any organic residue on the bottom. Here the ceramic was positioned so that an airpump pushed a big air bubble every 3 seconds which “caressed” the eggs, to simulate the oxygenating process done by the parents moving their fins to aerate the eggs.

To maintain a stable temperature, the tank was placed in a bigger tank filled with water and with a thermostat. This way it was possible to prevent sudden temperature changes which are potentially lethal for larvae.

Eggs hatched one or two days after being moved, though a few eggs failed to hatch and started decaying. A few larvae died soon after hatching, but still there was a good hatching percentage. After making sure that most of the eggs hatched, the ceramic decoration was removed, cleaned, and put back into the original tank. Any dead larvae or organic residue was siphoned from the tank being extremely careful not to suck away any live ones, as sometimes they rest on the bottom, weighed down by the still-full yolk sac.

Larvae Nutrition

Larvae were not fed for 48 hours after hatching. After this time period they were fed with newly-hatched artemia nauplii, as the first frenatus hatch happened before the rotifer culture was ready. It was a pleasant surprise to learn that frenatus can be reared with artemia nauplii, bypassing rotifers, probably because the larvae are slightly larger, for example, than Amphiprion ocellaris.

To give you an idea of the quantity of nauplii that were used, take a look at the following picture: larvae do not have to make a great effort to find one in close proximity to their mouth!

The maintenance was continued with a daily water change and adding nauplii. At this time it was very important to regularly remove the dead nauplii on the bottom, remember, the water is mature but the tank has no filter!

About a week after hatching, the larvae showed the first signs of metamorphosis, changing from totally see-through to showing some colors, and developing a better control of swimming. Up to this point the tank was totally empty, now it was time to insert some hiding spots and visual barriers.

The mortality rate was really high during the metamorphosis process; only a small percentage of larvae made it through. However, the survival rate has been increasing with the increasing team experience! It went from 4 surviving individuals to 15-20 per hatch in a very small amount of time.

Organizing the tanks

The parent couple, in the meantime, kept laying eggs, so a new tank was prepared for moving the ceramic with eggs. During all rearing phases, the larvae and/or little fishes were never fished out the tank, rather the whole tank was moved to minimize the stress.

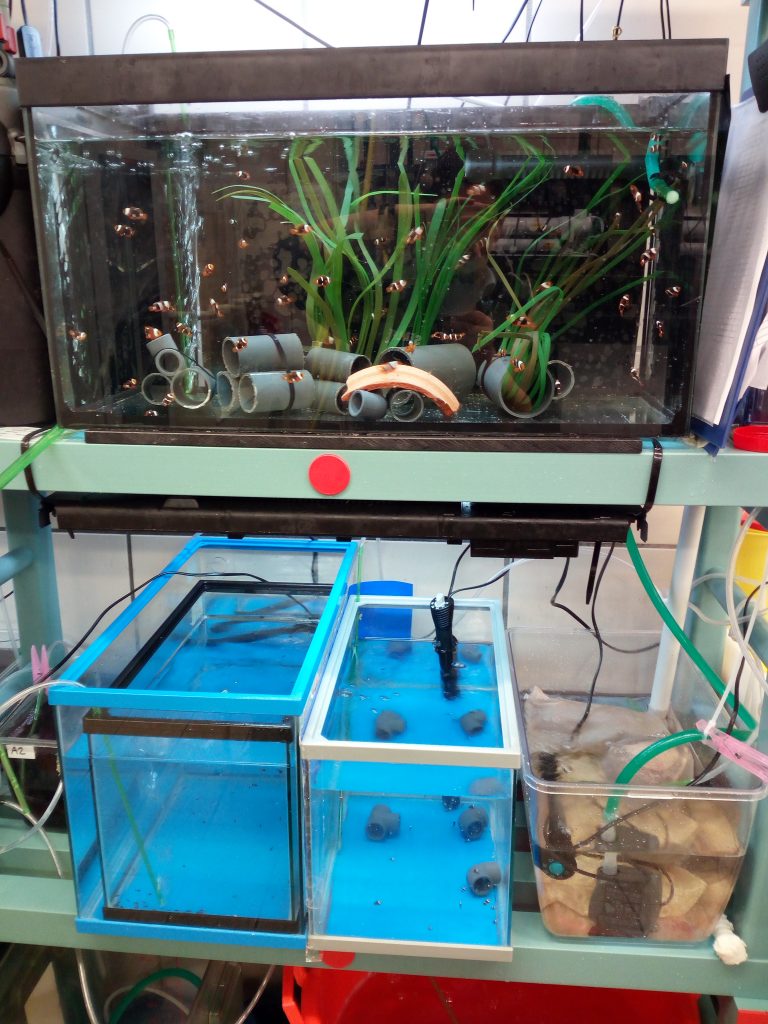

Once the individuals reached at least 0.5 cm in length, they were moved to a bigger system with a biological and mechanical filter. In the picture below you can see the 3 phases they went through during rearing. In the tank at the top almost-adult frenatus were fed 3 times a day, once with live artemia nauplii, the other two with frozen and dry food.

This process was possible because of the material availability of a center like Sea Life, but I think it could be replicated by any hobbyist with a fair level of experience and practice, together with material and time availability of course! The main difficulty when rearing clownfishes at home is the rotifers availability, but in the case of Amphiprion frenatus we managed to bypass their use, which is still essential in rearing Amphiprion ocellaris.

The story goes on with Amphiprion ocellaris

During this experience, a young couple of A. ocellaris started laying in another tank. Here, they initially laid on a live rock under their beloved anemone, which was impossible to remove. The team had the idea to place a small ceramic piece just under the anemone and, after a few days…

[by Giorgia Lombardi]

0 Comments