From the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies:

Baby fish breathe easier around large predators

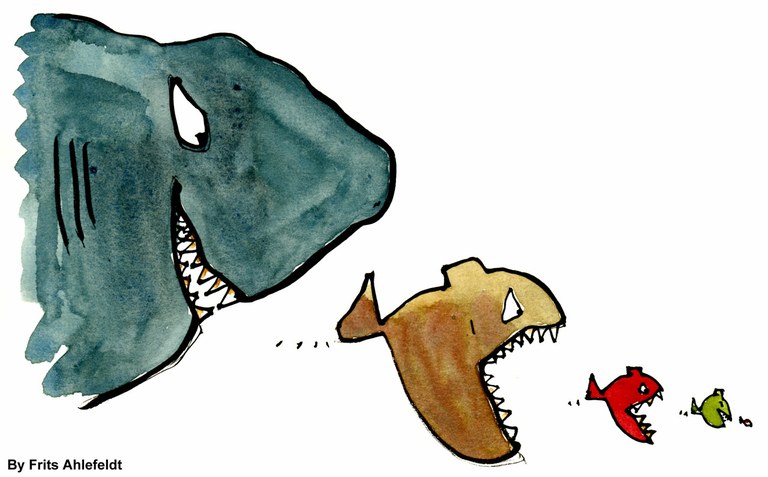

Scientists have discovered that the presence of large fish predators can reduce stress on baby fish.

Researchers from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University and the University of Glasgow have found that physiological stress on baby fish can be reduced by more than a third if large predatory fish are around to scare off smaller, medium-sized predators, known as mesopredators.

“Previous studies have proven that the sight of large predators can reduce the activity of mesopredators,” explains JCU’s Maria del Mar Palacios, lead author of the research. “But our study is the first to show that such behavioural control on mesopredators is strong enough to indirectly allow baby fish to reduce stress levels by more than 35 %.”

To obtain these results, scientists exposed baby damselfish to combinations of sensory cues (including visual and scent cues) from small and large predators.

Detailed measures of the behaviour and oxygen uptake (as proxy for “stress”) of the baby fish enabled researchers to understand the cascading effects that predators throughout the food chain can have on newly settled baby fish on the Great Barrier Reef.

JCU collaborator, Lauren Nadler, said the baby fish were very scared in the presence of mesopredators alone. However, all of the physiological stress disappeared if they added a large predator, which effectively suppressed all mesopredator activity. “By scaring the mesopredator, it seems as if the large predators are helping the baby fish keep calm and relaxed. They don’t need to worry anymore about the constant chases and threats from mesopredators”.

As with humans, it’s expected that a reduction in physiological stress should benefit their fitness and well-being.

“Animals have finite energy budgets, so by reducing the energy invested in anti-predator responses, baby fish should be able to invest more energy in growth and storage,” said Dr. Shaun Killen, a fish physiologist from the University of Glasgow who also collaborated on the study.

Professor Mark McCormick, who supervised the research, warned that although these findings are exciting from an ecological point of view, they could carry grave consequences for the balance of marine ecosystems.

“The ongoing overexploitation of large marine carnivores might allow an explosion of smaller, active predators that could not only kill, but also stress the population of baby fish that remain,” he said.

Paper:

M.M. Palacios, S.S. Killen, L.E. Nadler, J.R. White &, M.I. McCormick. 2016. Top-predators negate the effect of mesopredators on prey physiology. Journal of Animal Ecology.

0 Comments