By Luiz Rocha

I am sure by now most aquarium keepers know exactly what I am talking about when I say “twilight zone”, but I will take some time to explain it if you are hearing it for the first time. Twilight zone (or as it is known scientifically, mesophotic ecosystem) refers to deeper reefs, usually between 50 and 150 meters depth (or 180 to 500 feet). At this depth, the water column attenuates light making the area remain at permanent low light conditions, hence the terms twilight and mesophotic (which translates to middle light).

Typical Pacific twilight zone habitat. Photo by Luiz Rocha.

Reefs at these depths are very different from those that we are used to seeing. There are very few stony corals, but a lot of gorgonians, wire corals, soft corals, and sponges. Skeletons of corals that lived there a long time ago provide the structure. About 10,000 years ago, the sea level was 100 m lower than what it is today, and that’s where shallow reefs used to grow. As sea level rose to present levels, the coral that grew during that time “drowned”, but it now serves as habitat to a diverse invertebrate and fish community.

Because they are so deep, we know very little about those reefs. Even the most basic science of naming species (taxonomy) is at its infancy in this habitat, and we find species that are unknown to science all the time. The area is still unexplored mostly because it is very hard to reach. You can get to it either on a submarine, which is very expensive and not the ideal tool to collect and study fishes, or by technical diving, which is cheaper but riskier and requires a lot of training.

Entrance to the new “Twilight Zone” exhibit at the California Academy of Sciences. Photo by Luiz Rocha.

I have been fortunate enough to study this ecosystem for the past few years here at the California Academy of Sciences and just fulfilled one of my long term career dreams: sharing what I see on these dives with the public. Last summer we opened an exhibit filled with animals from the twilight zone, and just this week we updated several of our display tanks with fish that we brought from a recent expedition to Palau.

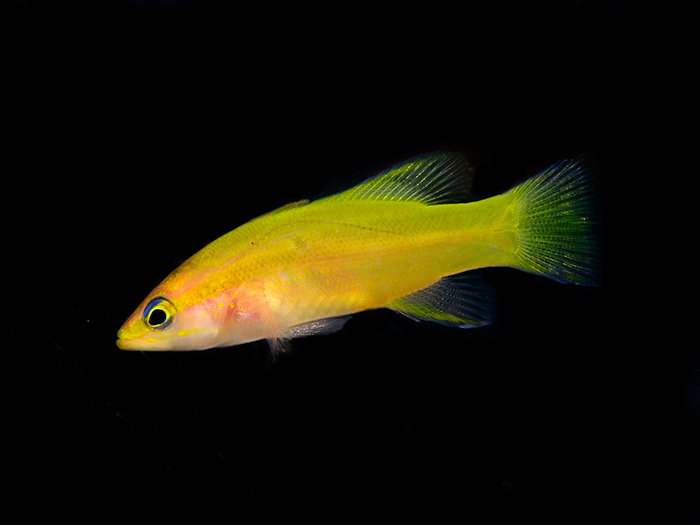

I will leave details about bringing those fish to the surface (we have a decompression chamber especially for them!) and keeping them alive to be told by my aquarium biologist colleagues, and here will focus on something that I hope is equally interesting, the fishes themselves, which are my specialty. So, after about an hour to prepare our rebreathers, the boat ride, another half hour to get ready to get in the water, and 5-10 minutes to descend to our target depth, we finally start catching fishes. We can usually divide the fishes in three general groups: a few have a very wide depth distribution and can be seen from the top of the reef all the way down to very deep areas. One example is Anampses melanurus. Most field guides and textbooks say that this species inhabits depths of up to 40m, but we collected this beauty at 100m depth.

Anampses melanurus. Photo by Luiz Rocha.

But most fishes we see here are only found deep. Because of the low light, there is very little algae, and many fishes feed on one of the most abundant food sources: plankton. One of the most numerous groups both in terms of number of individuals and number of species is anthias. They swim 2-3 feet above the bottom feeding on plankton, but quickly retreat back into the reef when we approach. We brought back three species from Palau, Pseudanthias calloura, P. parvirostris and P. smithvanizi. All three are normally only found in the Twilight Zone, but not very deep, and are most common between 60 and 80m depth. P. calloura is known from Palau and Indonesia, but it is likely more widespread and wasn’t detected in other places because of it’s depth range. P. parvirostris is known from several locations through the Indian Ocean, coral triangle, Palau, Japan and Australia. P. smithvanizi has a similarly wide range but extends farther into the Pacific. All three species have stunning colors, especially the males as is usual for anthias.

Pseudanthias calloura. Photo by Luiz Rocha.

Pseudanthias parvirostris. Photo by Luiz Rocha.

Pseudanthias smithvanizi. Photo by Luiz Rocha.

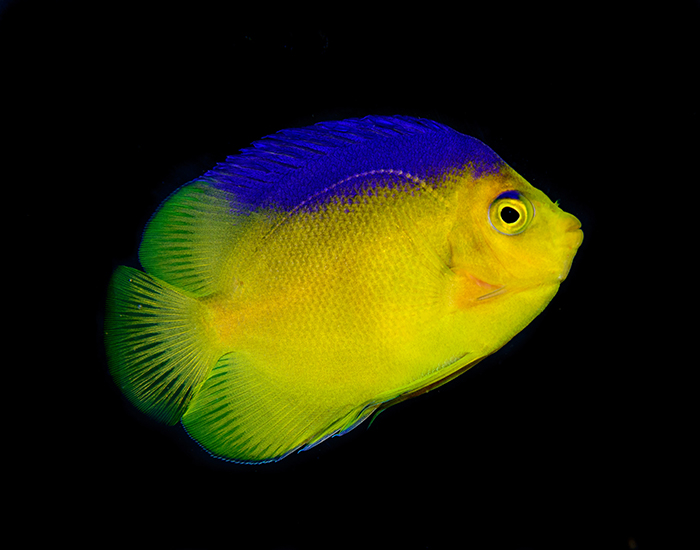

The other very abundant food source for fishes at those reefs is invertebrates that live on the bottom. Angelfishes, especially of the genus Centropyge, are common and diverse at those depths. We collected two in Palau, Centropyge colini and C. fisheri. Of the two, C. fisheri is much more common and has a wider depth range from 30 to 120m depth. We only saw one C. colini, not necessarily because they are rare, but because they are very picky about habitat. I have only seen four or five C. colini during my thousands of dives, and all of them were in places with large caves and overhangs. When we find the right habitat it is almost certain that we will find them, but the right habitat is very hard to find, especially because at those depths we only have 10-15 minutes of working time.

Centropyge colini. Photo by Luiz Rocha.

Centropyge fisheri. Photo by Luiz Rocha.

Another group of bottom invertebrate feeders that is often seen in deep reefs is butterflyfishes. In Palau, the most common twilight zone butterflyfish is Chaetodon burgessi. We brought a lot of them to the Academy because they are great to control aiptasia and other hydroid pests in our display tanks!

Chaetodon burgessi. Photo by Luiz Rocha.

And that brings us to the most exciting fish in my opinion, the ones that only occur in really deep reefs. Two examples from Palau are Liopropoma latifasciatum and Bodianus leucosticticus. Both have wide geographic distributions, but are rarely seen because of their depth ranges: we only start seeing good numbers of them in reefs deeper than 100m. Of these two, the Liopropoma sometimes makes it into the aquarium trade because it tends to come up shallower in colder areas like Japan, but the Bodianus is very rare. Both are very hard to catch because they love to run in and out of little caves between the rocks, but once they are in the tank they are voracious eaters and do great!

Liopropoma latifasciatum. Photo by Luiz Rocha.

Bodianus leucosticticus. Photo by Luiz Rocha.

To me, the whole point of the complex operation of bringing these fish back to a public aquarium is not just the science that we do in the process, but also the awareness that we raise. Most of these deep reefs are not included in marine protected areas because people don’t think deep reefs are being impacted. But they are! We see broken fishing lines, trash, and a lot of sediment on those reefs all the time. So the take home message here is that there is this hidden marine wonderland at depths that the normal diver can’t reach, but this entire habitat is unprotected and threatened. Your part here, as an aquarium keeper, is to tell this story to as many people as you can, even if you are not fortunate enough to keep a fish from this habitat, but especially if you are!

Photo by Luiz Rocha.

0 Comments