Parapercis natator, a species predominantly found in the Ryukyu Archipelago of Southern Japan. The epithet “natator” is latin for “swimmer”, which aptly describes the behaviour of this unusual species; the species prefers hovering a couple of meters above the substrate, uncharacteristic of other Parapercis spp. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

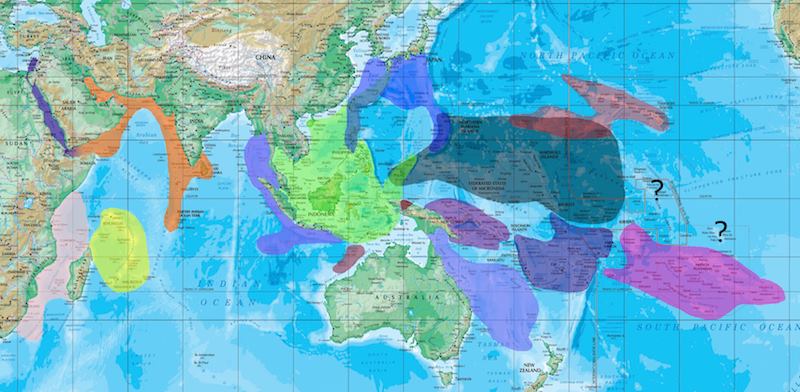

The Philippines and its satellite islands form one of the richest hotspots for biodiversity in the Coral Triangle as well as the Western Pacific Ocean. It is here that many of the characteristically charming species that we’ve come to know and love originate – not just in terms of collection locality, but evolutionary as well. This imaginary, intangible boundary that serves to distinguish the region from its surrounding is deemed as a “biogeographic hotspot of endemism”, and in examination of the diverse fauna of the Indo-Pacific, we find similar examples of endemic biodiversity peppered throughout the region.

The speciation model for most reef fishes follow this biogeographic jigsaw rather faithfully, especially in evolutionary volatile genera like Cirrhilabrus, Pseudanthias, Chrysiptera etc. Unlike species such as the Moorish Idol that occur unchanged throughout these regions, these small fishes with comparatively shorter larval durations are rather incapable of crossing vast expanses of water to colonise new territory as aggressively as the former. As such, they are generally restricted to the regions that they occur in. In the event of population dispersal into neighbouring ecoregions, adaptation and evolution usually occur due to the isolation of genetic flow, leading to speciation and the rise of sister counterparts.

This is quite wonderfully seen in Cirrhilabrus, for example, but because evolution is of a continuous and intangible nature, it is not always easy to see; visually at least. In the words of Richard Pyle, I quote, “at some arbitrary point in evolutionary time, the gene flow between populations becomes low enough, and phenotypic/genotypic variation sufficient enough, that a competent taxonomist decides that communication is best served through labeling the populations with different specific epithets.”. In a nutshell.

So what does this all mean and how does it relate back to us? The past year has been interesting, to say the least, in that a large handful of previously known “Japanese endemics” have been discovered in the Philippines. These crossover species, naturally, attracted quite the commotion. However, looking back at the biogeographic model, perhaps that enhanced level of shock is unwarranted.

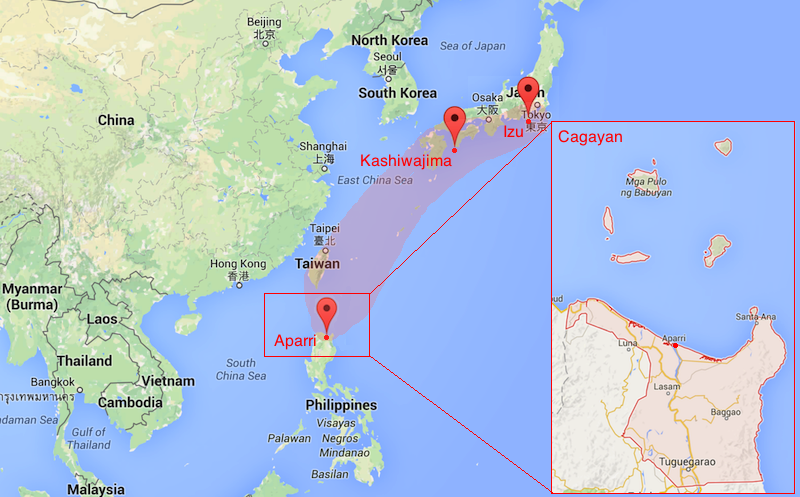

The unique location of Cagayan sits right in the middle of two ecoregions. To the north (in red) lies the Ryukyu Archipelago of Southern Japan, and to its south lies the Philippines proper.

These Japanese species were, and to a great extent, (are still being) collected in the Philippine’s northernmost tip. Aparri, Cagayan, is unique in that it straddles two biogeographic ecoregions. To its north lies the Ryukyu Archipelago and Southern Japan, where the tropical waters hold much of Japan’s characteristic piscine fauna. To its south lies the Philippines proper. Cagayan is therefore the southernmost limit for most of the species occurring in the Ryukyu Archipelago. Few species, like Cirrhilabrus cf. lanceolatus (the pintail fairy wrasse), reach their distribution limit in more southernly regions such as Cebu, but in general, they are rare there and most never get past Luzon.

These are the Southern Japanese species that have been documented to occur in Cagayan thus far:

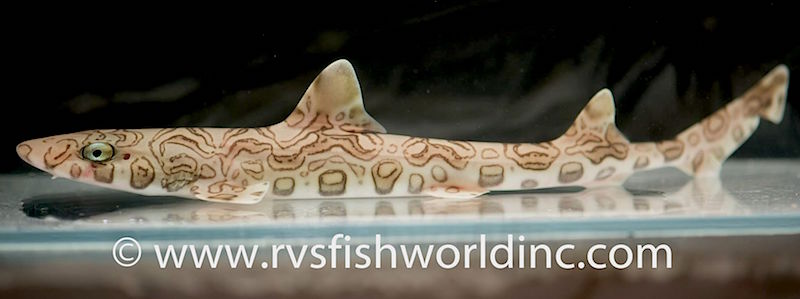

Nearly all these species are endemic to the geographical region encompassing Southern Japan, the Ryukyus and Taiwan. The opening of Cagayan as a substation for ornamental fish collection by RVS Fish World has revealed itself as the southernmost distribution limit for these fish, highlighting the unique biogeography that this region of the Philippines enjoys. There is one more Japanese species documented to occur more southernly in the Philippines Archipelago, and that is Navigobius dewa. There is no doubt that it also occurs here in Cagayan.

0 Comments