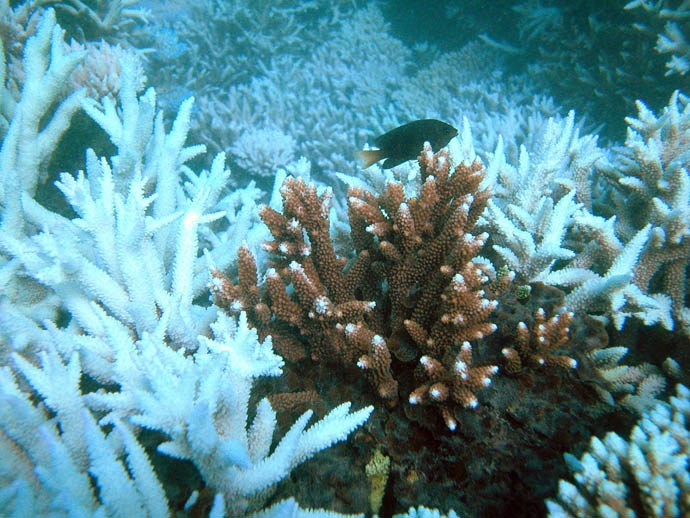

If susceptible table and branching species are replaced by mound-shaped corals, it would leave fewer nooks and crannies where fish shelter and feed.

“Coral reefs are sometimes regarded as canaries in the global climate coal mine – but it is now very clear than not all reef species will be affected equally,” explains lead author Professor Terry Hughes, director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University.

The emerging picture, he says, is one of ‘winners and losers’, with some corals succeeding at the expense of others. Rather than experiencing wholesale destruction, many coral reefs will survive climate change by changing the mix of coral species as the ocean warms and becomes more acidic.

This in turn has implications for humans, who rely on the rich and beautiful coral reefs of today for food, tourism and other livelihoods.

“A critical issue for the future status of reefs will be their ability to provide ecosystem services like reef tourism and fishing in the face of the changes in species composition. For example, if susceptible table and branching species are replaced by mound-shaped corals, it would leave fewer nooks and crannies where fish shelter and feed” their report in the journal Current Biology cautions.

The research team carried out detailed studies of the coral composition of reefs along the entire length of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. They identified and measured a total of 35,428 coral colonies on 33 reefs from north to south. Studying corals on both the crests and slopes of the reef, they found that as one species decreases in abundance, another tends to increase, and that species wax and wane largely independently of each other.

“Previous studies around the world have focused on total coral cover as the main indicator of reef health, but we wanted to explore what happens within the coral assemblage itself. The way these individual species are mixed together is extraordinary flexible,” Prof. Hughes explains.

“We chose the iconic Great Barrier Reef because water temperature varies by 8-9 degrees along its full length from summer to winter, and because there are wide local variations in pH. In other words, its natural gradients encompass the sorts of conditions that will apply several decades from now under business-as-usual greenhouse gas emissions.”

This study has given us a more detailed understanding of the sorts of changes that could take place as the world’s oceans gradually warm and acidify.

“And it has increased our optimism about the ability of coral reef systems to respond to the sorts of changes they are likely to experience under foreseeable climate change.”

The good news from the research, says Professor Hughes, is that complete reef wipeouts appear unlikely due to temperature and pH alone. “However, in many parts of the world, coral reefs are also threatened by much more local impacts, especially by pollution and over-fishing. We need to address all of the threats, including climate change, to give coral reefs a fighting chance for the future.”

Their paper Assembly rules of reef corals are flexible along a steep climatic gradient by Terry P. Hughes, Andrew H. Baird, Elizabeth A. Dinsdale, Natalie A. Moltschaniwskyj, Morgan S. Pratchett, Jason E. Tanner and Bette L. Willis appears in the journal Current Biology.

This study has given us a more detailed understanding of the sorts of changes that could take place as the world’s oceans gradually warm and acidify. Rather than experiencing wholesale destruction, many coral reefs will survive climate change by changing the mix of coral species as the ocean warms and becomes more acidic.

More information:

Prof. Terry Hughes, Director, CoECRS, +61 (07) 4781 4222 or +61 (0)400 720 164

Jenny Lappin, CoECRS, +61 (0)7 4781 4222

Jim O’Brien, James Cook University Media Office, +61 (0)7 4781 4822 or 0418 892449

0 Comments