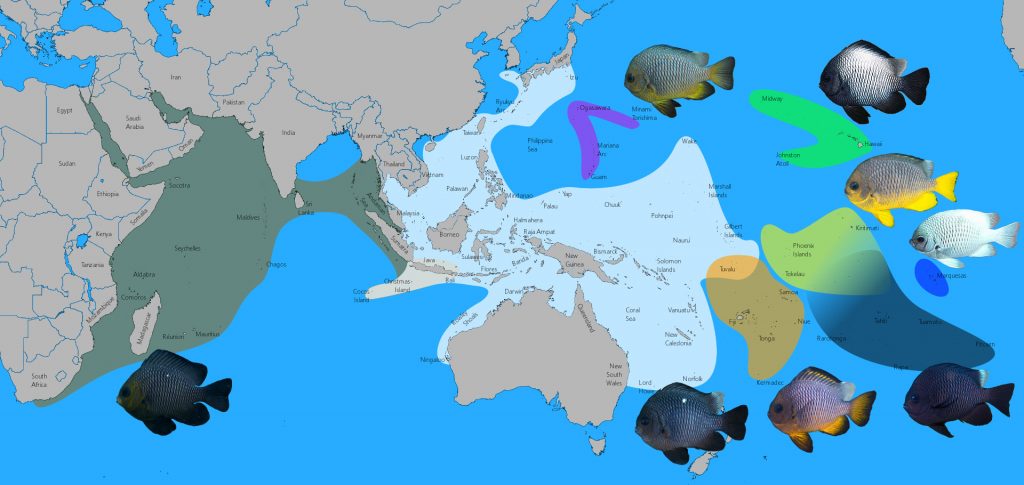

Like so many widespread coral reef fishes, the ubiquitous Domino Damselfish (Dascyllus trimaculatus) is really a mélange of subtly different regional populations. Each of these unique forms is readily recognizable relative to its neighbors; however, their tremendous similarity to one another has led researchers to lump them together as a single heterogenous “species”. But, as I shall endeavor to illustrate here, these are truly distinct fishes in an evolutionary sense and deserving of recognition as separate taxa.

Mature males, such as this one from Okinawa, can appear ghostly white, obscuring some of their diagnostic differences. Credit: Takeru Tsuhako

Before we delve into the nitty gritty, a word needs to be said about the nature of these lovely fishes. The Domino Damselfish (AKA the Threespot Damselfish) sports a characteristic juvenile coloration, with a jet black body marked by a white spot dorsally behind the eye and another roughly midway along the back. These eventually fade in the adult, with the anterior spot disappearing entirely and the posterior spot becoming highly reduced or absent completely. Another important variation can be seen in the ability this fish has to lighten its body, being able to change from the usual black to a ghostly white. This is a behaviorally controlled response that likely has to do with a territorial or mating display, though little research has been documented on this phenomenon.

It’s important to appreciate the variable nature of this fish with respect to these ontogenetic and behavioral factors. When we are comparing different populations across the Indo-Pacific, we need reliable diagnostic traits that are consistent. For some regions, the adults consistently display the whitened phenotype throughout their adult lives, while in other regions this color seems more transitory. Similarly, the presence or absence of the white spots that give this fish its common name are equally unreliable as an identifying characteristic. With all that said, we can now begin to discuss this fish in greater detail. [For the sake of this discussion, I’m going to coin some new common names.]

Blacktip Domino Damselfish (Dascyllus trimaculatus)

The type locality for this species is in the Red Sea at Eritrea, which means that this region is the only place we can be sure D. trimaculatus occurs at. Thus far, genetic study into this group has failed to reveal any major differences between the populations found in the Indian Ocean and Red Sea, but these datasets have been rather limited in their scope thus far. In the related D. aruanus, the Red Sea population has been shown to be somewhat distinct in its genetics from those sampled elsewhere in the Indian Ocean.

In examining in situ photographs of this fish from across both the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, I can find no obvious phenotypic difference between them (though, of course, it’s quite possible there may be meristic subtleties). However, there are some important details that support this fish as distinct from those found in the Pacific. The most obvious is the dark posterior tip of the dorsal fin, which, in the Pacific Ocean taxa, is clear or white. This is especially prominent when this fish enters its “white morph”, as the dorsal fin retains a contrasting black margin across its full length.

The other difference to look for is the tan or brown hue commonly seen on the head. This is a more unreliable feature that is only applicable to mature specimens, and, even then, darker individuals seem to exist. Ambient lighting, flash photography and the fish’s behavioral color can all impact the appearance of this trait as well, but, that being said, this light-colored head is distinct enough relative to the dark-headed Pacific forms that it allows for an easy identification when it is observed. Aside from the Red Sea, you can find the true A. trimaculatus along the East African coastline to Durban and east into the Andaman Sea and Cocos-Keeling Island. It’s likely also present in the Java Sea and around Bali, where it could be expected to hybridize with the local Pacific population.

0 Comments