Curaçao log: My traveling muse

Day 2 – October 12, 2015

Monday.

I’m writing this log on a ship! The R. V. Chapman. Things got a little bit gung-ho today. Well, a lot gung-ho. Sweet serendipity comes not nearly enough in a lifetime, but when it does, you take it. In retrospect, the momentary freak out was a little unwarranted. Truth be told, it’s likely I would have done it again in an instance. The human brain doesn’t work too well when its over pumped with serotonin, adrenaline and excitement. Or maybe it does. I’m not a neurobiologist, I wouldn’t know. Cirrhilabrus phylogeny and apple pies. I do know those.

I suppose, as with any log, we should start from the beginning. My feeble mental capacity is still finding it difficult to comprehend all of this. Like a Spiderman lover at a Comic-Con, getting his book autographed by Toby Maguire (I do not like Andrew Garfield), my excitement was palpable. Like an adrenaline casserole, I was so ready for the world. That is how I do.

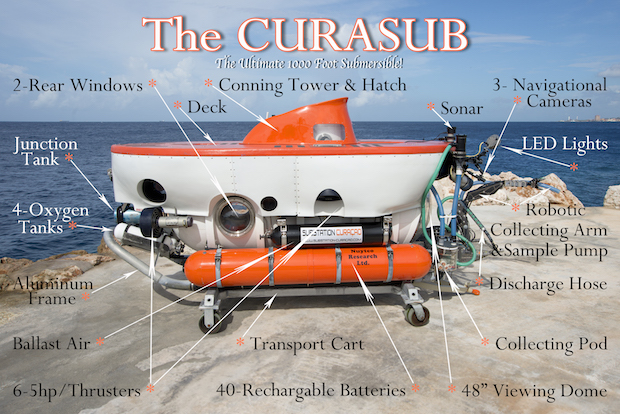

Vanessa was up early as well. Today was a tranquil. The sea dyed azure, lightening to a scintillating malachite toward the shore. There were lots of Frigate Birds out this morning, riding the thermals effortlessly. I remember trying to count their wing beats, but they never seem to flap at all. Like a kite at the mercy of the wind deities. Day dreaming aside, today is Curasub day! Today is the day where I, a 5’8 human of flesh and bones, get to sit in the dream machine. I had in my mind a mental checklist of fish I wanted to see. Liopropoma, Lipogramma, Prognathodes, etc. The Curasub, as awesome and spellbinding as may be, would ultimately serve as a metallic conduit for my list. That was the priority. Fish is always the priority.

We walked to the substation office, a stone’s throw away. I had my bag with me. Camera, laptop, you name it. Cursed with an unwieldy gait, I would soon realize that all of this would be unnecessary. Enter the substation office we did, and across the room was a familiar face. It’s Barry Brown! I know that man. Well, I didn’t know him know him, but I read his blog. Barry bridges the gap between the happenings in Curaçao and the rest of the doe-eyed world. He takes incredible photographs of the deepwater fish collected by the Curasub and the Smithsonian Institution.

But before I could exchange pleasantries, Vanessa and I were greeted by another person. A svelte woman named Barbara. Olive skinned, and coal colored hair. She was one of two pilots that operated the curasub. We had to fill in a waver, submit our height and weight, medical conditions etc. Standard stuff. I usually have my personal particulars well remembered, but I had an itching suspicion that my weight was now no longer the same. Why would it? I had just spent almost a month in the Midwest. Deep dish pizzas in Chicago, mountain dew and burgers in Omaha, Texas-ing in Texas. Texas is weird. No really it was. My facebook would agree with me, so would my atherosclerotic plague.

Once that was all done, Barbara conducted a safety brief, and a rundown of how the curasub works. It came as a pleasant surprise, knowing that in failure, one could live unharmed for four days in there. That would be cool, except for the human body’s inconvenient need to eliminate waste (for which there were bags). We were also introduced to Bruce. His resemblance to Owen Wilson was uncanny. The long blonde hair really made the look. Bruce, like Barbara, was a curasub pilot as well.

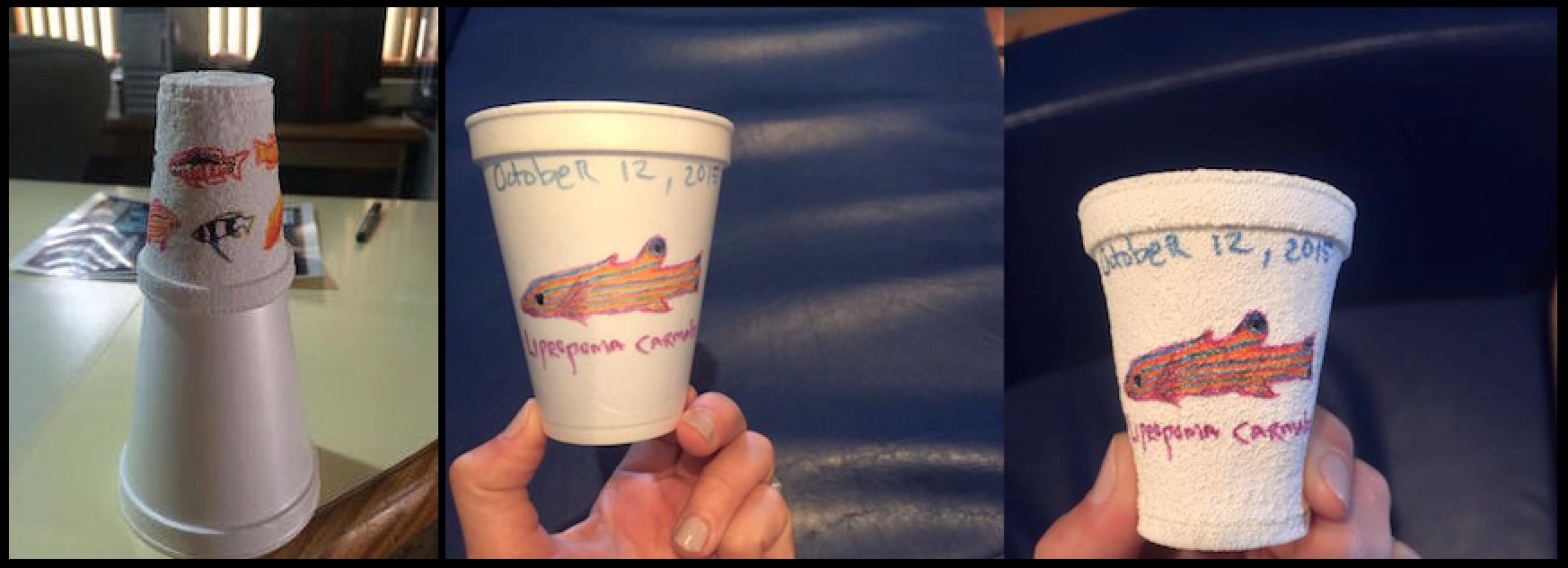

My styrofoam cup, with Plectranthias, Liopropoma, Lipogramma. Not shown on the other side are Prognathodes, Gonioplectrus and Serranus! Photo credit: Barry Brown

Barry made an appearance again. Styrofoam cups in his left hand, and sharpies in his right. He muttered, in slight amusement, that it’s customary for all curasub visitors to draw, in whatever they may please, on the cups. The Styrofoam cups would later be placed in a mesh bag, attached to the outside of the curasub, and taken down to depth. The beauty of Styrofoam is that because its mostly air, its compressible, and unlike a plastic cup, will not crumple. We were told this cup would shrink to at least half its size. I drew a series of local Curaçao fish that I’ve seen and photographed over the years. Vanessa drew a Liopropoma carmabi and Lipogramma evides.

Dutch came by shortly after, signaling that it was time to take the curasub for a spin. He mounted a crane, yellow as corn. With dexterity and poise, he lifted the stationary submersible from its garage housing and onto the loading platform. The vertically oriented hatch was opened, and Dutch, as quickly as he appeared, disappeared down the hole. Bruce was the next to enter. Vanessa followed, and then I. The curasub sits a maximum of five people. A pilot in the middle, and two passengers at the front. They were to lie on their chest, with their heads oriented toward the convex bubble. Dutch usually commands the left side, where he controls the mechanical arms from the inside. The back of the curasub has space for two more passengers, but there, they must assume not a prone position, but sitting down instead.

For a postcard worthy, semi-cliché tourist shot, Vanessa and I lay, in prone, at the front. Barry had already suited up with his camera on the outside, and would proceed to meet us at about 60ft. There, he took a couple photos of us. Once that was done, Vanessa switched positions with Dutch, and we began our descent. Like a dying candle, the light flickered and wavered. As the amount of life giving light decreased, the depth counter above my head increased. 100…150…200… we continued down until we no longer saw the shallow water species. Chromis cyanea started disappearing, and so did the Holacanthus angelfish. The Royal Grammas persisted, but they too started fading away by the time we got to 250ft.

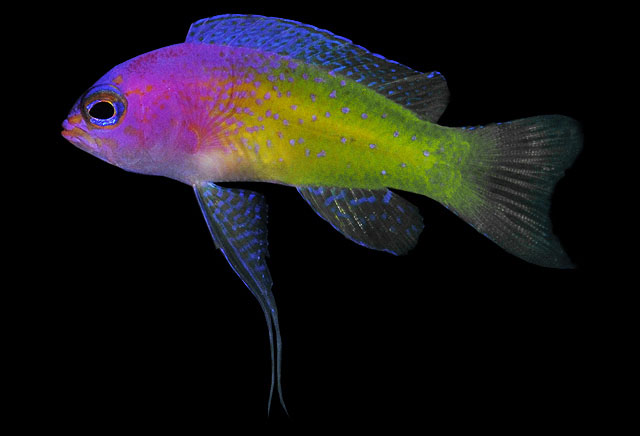

At 260ft, I saw my first Lipogramma klayi in situ. In this beautiful fish, the anterior body is orchid, pixilated into a rich goldenrod posteriorly. The fins are blue dusted, wispy, and very elegant. The species is cautious, yet dashing in nature, and very difficult to capture. It is not uncommon in rubble pans around 250-300ft, but becomes progressively rarer at far greater depths. Dutch captured two specimens at the first location, and we continued to see it no more than a dozen times subsequently. Lipogramma klayi is the commonest member of its genus at this depth range, and can be found in all locations where suitable habitat is presented.

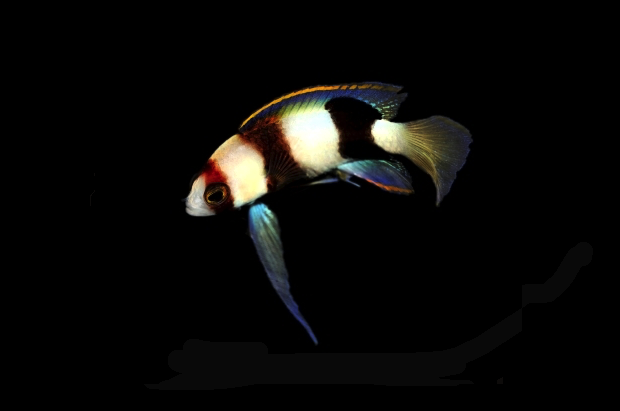

As the rubble landscape fused into gentle slopes terraced with layered ledges, a predominantly different species takes precedence. Liopropoma mowbrayi is brick red, with two ocelli on the anterior dorsal fin and the anal fin. This species is shy, and very retiring. It frequents shallow overhangs, formed by horizontally protruding plates pressed tightly against the substrata. It makes calculated turns in the cracks and catacombs that lace the reef, but can be taken with some effort during its uncommon forays into the open. The habitat is shared with a sympatric, but more beautiful member of the same genus. It is Liopropoma carmabi, or more aptly known as the candy bass.

L. carmabi is of the same size and form of L. mowbrayi, but is decidedly more colorful. This is arguably one of the most beautiful serranids in the Atlantic. The fish is striped in a rich neon orange, alternated with purple of similar intensity. The posterior dorsal fin, as well as both caudal lobes, are marked with a blue ringed ocellus. L. carmabi frequents the same conditions as L. mowbrayi, but is never common. However, it cannot be considered rare, occurring sporadically in suitable habitats. Both species disappear past 400ft, where they are replaced by two larger and more boisterous species – Liopropoma olneyi and L. aberrans.

As the curasub descended into 350ft, the ambient lighting becomes progressively more subdued. Here, the usefulness of the headlights becomes increasingly apparent. The air cools to a comfortable temperature, making breathing easier and more effortless. Beads of condensation started forming on the interior walls, trickling down the sides. In once instance, while fiddling with my wet sleeve, a large bullet shaped fish appeared. It was powerful, quite handsome and very nonchalant. It was Serranus luciopercanus.

Serranus is highly diverse, with multiple species spanning a myriad of forms and shapes. They’re classified phylogenetically into various complexes and groups, a task most onerous undertaken by brilliant minds at the Smithsonian Institution. I’ve only ever seen the juvenile of Serranus luciopercanus in the trade, never an adult, and certainly not in the field. S. luciopercanus is cloud grey, with a subtle slating of periwinkle blue. The dorsum just below the dorsal fin is stepped with black horizontal bars, each outlined by a glaucous margin. The caudal fin is large, hyaline yellow and deeply forked.

Antilligobius nikkiae. The specific epithet “nikkiae” was named in honour of Dutch’s daughter, Nikki. Photo credit: Barry Brown.

S. luciopercanus cruised along an open faced slope, giving way to a new fish that was markedly smaller. Antilligobius nikkiae. In this, the only member of its monotypic genus, the body is silvery with a yellow equatorial belt. The eyes are rimmed in a metallic cobalt. Like all gobies, A. nikkiae has two dorsal fins. The anterior is falcate, tapering and hyaline. The posterior is marked with a yellow band similar to that of the body. Its caudal fin is roughly rhomboidal, with the central rays extending to a short filament. Like Coryphopterus, this species frequents steep, vertical ledges where they hover in groups. Dutch was particularly excited with this species, seeing as it was named after his daughter. We saw multiple groups of two to a dozen individuals at all suitable habitats between 3-450ft. The species is very small, and in the field, is diagnosed only by its shimmery blue eye.

By now the curasub was at 440ft. The condensation was starting to seep into my shorts and socks. Bruce hovered over a rubble pan, where a pair of Lipogramma were taking residence. L. klayi was starting to disappear at this elevation, and a different Lipogramma species was becoming increasingly evident. It was banded, like a convict, in black and white. The pelvic fins were, as with all members in this genus, long and very trailing. The fins are sapphire tinted, crystalline almost, and edged ever so slightly in yellow. This miniscule beauty commands exorbitant prices in the aquarium trade, where it is known incorrectly as Lipogramma evides. It seems almost futile to correct this erroneous naming, now that it has become so pervasive in aquarium culture. The real L. evides is characterized by having less pronounced banding, and a large, prominent ocellus on the posterior soft dorsal fin. In all technicalities, this banded beauty should be known as Lipogramma cf. evides.

As we hit 450ft, we decided to head back up. By now we had spent close to two hours. It seemed preposterous, and ironic, how time crawls to a near halt on land, but in the curasub, it whizzed by ever so quickly. During the ascent, at about 430ft, we hit a very productive patch of reef teeming with life. Liopropoma olneyi and L. aberrans made a quick cameo. Too brief to capture any real footage, but just enough exposure to correctly identify the species. Unlike L. mowbrayi and L. carmabi, these attain sizes up to six inches, and are bold, brazen, and very showy. A pair of Gonioplectrus hispanus cruised by quickly as well, and while I didn’t manage to get a video of those, I was pretty sure that wasn’t the last we’ll see of that species.

On a steep slope at 400ft, behind an immense gorgonian, a male Pronotogrammus martinicensis appeared. The males are peach, inscribed on the anterior with a labyrinth of gold striations. These tresses merge to form an orange saddle that spreads midway down the body. The posterior is fairly unmarked. The females are very common and are considerably less flamboyant. This species is very common at all depths starting from 200ft, persisting even at depths hitting beyond 600ft. The species appears to inhabit a wide variety of habitats, from rubble pans, to isolated rock bommies surrounded by sand. However, they seem to prefer inclined ledges and walls, especially those permeated with holes. The more common females are often taken together, while large males are comparatively rarer, occurring as sporadic individuals traipsing about loose groups.

Continuing on our ascent, the air significantly increased in temperature, making breathing less comfortable. Manuel and Joe met us at 110ft, where they took over our collection bucket. Catching fish with two robotic arms isn’t easy, but there are certain skills involved that would require months of training. Like a lucid dream, my virgin curasub experience was over. Our cups turned out really well, a physical memorabilia to a morning well spent.

Dutch then made a proposal that threw Vanessa and I into somewhat of an existential crisis. He was heading out to Klein Curaçao later that afternoon, with the curasub, on his big research vessel, the R. V. Chapman. Klein Curaçao, literally translated to “Little Curaçao”, is an uninhabited island south-east of Curaçao. The fauna here is supposedly very different, and Dutch was planning to do a mini expedition with his team. Seeing how enthusiastic and successful our first submarine dive went, Vanessa and I were invited on this trip. The only problem standing between us and this once in a life time event was that we fly back to Florida tomorrow. The expedition to Klein Curaçao would last three days. So after some thought, we rescheduled our flights to accommodate our extended stay in Curaçao. Really, now that I’m writing this, how on earth was that even a problem? An existential one no less. Foolish.

The Chapman was slated to leave after lunch. Vanessa and I were left to our own devices, and were told to report back at the substation office a little after noon. Still on a celestial high from the curasub dive, we decided to go for lunch, which of course, was had over an incessant verbal vomit of fish related musing. I remember stopping momentarily, mid conversation, to photograph some birds that were nearby. A beautiful hummingbird had perched on a branch just across from our table. Frigate Birds that were soaring the skies from this morning were still hanging around, making easy subjects for photographs. I thought this was pretty random, but the photos turned out pretty decent for a mid-lunch session.

Safe to say we made the right decision extending our stay. We met at the substation office as planned, after lunch, where two new characters were introduced to us. Cristina, right hand to the Smithsonian Institution’s famed Dr. Carol Baldwin, and her friend Katrina. Together with Dutch, Barbara, Bruce, Bryan, Manuel, Joe and a whole ship crew of other people, we began heading out to pier where the Chapman was docked. The curasub was loaded onto the ship, and so began our journey to Klein Curaçao.

It’s funny how things turned out. We were scheduled to leave tomorrow, but now I’m writing this entry from the comfort of my bunk, on the brilliant and immense Chapman. Which, by the way, is ridiculously comfortable. My room even comes with its own shower, complete with decorative fish portraits. The crew on board is fantastic, some familiar faces, and some new characters. The three hour boat ride to Klein Curaçao is nearly over, and in the darkness of night, I can see our destination approaching. I’ll pen the rest of my thoughts down in tomorrow’s log. Cristina and Katrina are in charge of music for tonight’s dinner. I’m going to try catch a flying fish. There’s no wifi on board the Chapman, but I think we’ll be fine. The company’s a delight, the sea breeze is fantastic, and tomorrow’s another day. Wonder what we’ll see down there.

My more than comfortable bunk room, complete with bed, air conditioning, a study, a toilet and rare fish portraits!

Lemon is a watery treasure. An entertaining and smart guy. My honeymooned was on Curacao and I am enjoying his travel log.