Curaçao log: My traveling muse

Day 3 – October 13, 2015

Tuesday.

The sun has set hours ago, casting the sky into a featureless obsidian. But unlike the hapless humans, creatures of the ocean seek solace and comfort in the stars and spotlight, inching their way towards the steel hull of the Chapman. A condition most favorable to pen down my thoughts, for today was nothing short of exciting. As I surround myself in the rhythmic sloshing of the waves, I pour my memories into this entry. Fluid consciousness seeks nothing more than a paper on which to paint, and like a silent metronome, my day began at the crack of dawn. With Bruce and Dutch waiting, and the curasub humming, today would prove to be an intense tango in the twilight, a moment filled with piscine enthrallment.

We wasted no time in setting off. I fondly recall a smidgen of toothpaste still present at the corner of my lip. Hair a mess, clothes crumpled, I went from supine in my bunk bed to prone position in the curasub faster than you can say Prognathodes. The air is still and fraught with science. Serious science. Today, fancy alcoholic beverages were not to be had. It was all about the fish, and all about the fish it shall be. Something that I am more than perfectly okay with.

We’re no longer on the mainland, but instead, are 42.6km away in Klein Curaçao. A little island inhabited by none. The Chapman was docked about a hundred feet from shore. Bryan made preparations for the curasub launch as usual, and we climbed in. Vanessa stayed on board for the next run after lunch. She was thinking of swimming to shore to check out the sights on Klein Curaçao. I might do that tomorrow instead. There’s an eerie lighthouse that permeated the land with a tangible presence. That looked interesting.

Anyway, the launch zone was only a couple feet away from the Chapman. The stark contrast between aquamarine and cobalt signaled the presence of a steep drop off. Above, a cloud of Creole Wrasses paraded, like gatekeepers of the imminent deep. Following a towline, we descended down the drop off. A curious pair of Pomacanthus paru, colloquially known as the French Angelfish, followed our bright orange submersible until it was orange no more. Everything’s colored a monotonous blue down in the deep. The drop off gradient at this location was significantly steeper than that in Curacao, but it was also extensively permeated with holes, riddling the reef in a catacomb of sorts.

Our objective this trip was to look for Plectranthias garrupellus, The Apricot Bass. This fish attains a standard length no more than three inches, but what it lacks in size, it makes up for in beauty. As the “apricot” moniker suggests, the fish is luxurious orange, fenestrated and ramified in a series of alabaster stripes. Colorful no doubt, but the species is taciturn, preferring to shy away in seclusion. With a five-ton submersible whirring through the reefs and blasting the habitat with light, this task immediately becomes one of onerous difficulty.

As the curasub descended to 250ft, I noticed a wispy, spectral character undulating in slow motion under a ledge. It was distinctively shaped like a scimitar, with a longitudinal black stripe tracing its figure equatorially. As we got closer, it immediately became apparent what this mysterious figure was. Equetus lanceolatus, also known as the Jackknife, is an iconic denizen of the Western Atlantic. This species is easily diagnosed by its distinctive coloration and body profile, and is easily approached by divers. The Jackknife is common between 10-60m (30-200ft), where it peruses the substrate in search of worms and mollusks.

Moving slightly away from the Jackknife, another species of similar monochromatic somber made its presence known. It was large and skulking, but powerful and distinctively bass like. It was Serranus phoebe, and it paid no attention to us as we cruised along. By now we were hitting 300ft, but we weren’t deep enough to encounter our target species. The Apricot Bass prefers depths in excess of 400ft, and is closely associated with loose rubble and shallow ledges, much like Lipogramma.

As the curasub approached a cluster of boulders at 400ft, the seemingly lifeless aura was dispelled by the emergence of two fish. Liopropoma aberrans and L. olneyi. Two sisters, both reeking of familiarity. It was only two days ago that we saw both of them up close at the substation. The pair here was distinctively bigger, more robust, and commanded our undivided attention. Regal and majestic as they were, their looming presence was quickly overlooked by something a little more unobtrusive. In the corner, amidst a pile of rubble, something small was hovering.

The fish was small, barely two inches in length, but sported a ground color of opaslescent white. Two black bands were present along the anterior body, one of which concealed its eye. The posterior was branded in a suffused olive, upon which a large and prominent ocellus took precedence. This little bass recalled Lipogramma cf. evides that was addressed in my first entry, but was significantly larger and markedly different in pattern. It was Lipogramma evides, the real McCoy. In close examination, the two are immediately different, with L. cf. evides most likely being an undescribed cryptic species. What’s unusual is that both species occupy the same niche habitat, and are therefore sympatric. Could the similarities in coloration be convergent? Such is the intricacies and mysteries of nature. We managed to collect one specimen from this location.

By now we had reached 550ft. The environment was dark and somewhat depressing. The spotlight from the curasub had shone against a ledge face, and part of it was reflected back in a silvery shimmer. Prognathodes guyanensis. A majestic adult was spotted pressed against the very habitat that it is said to prefer. I’ve read numerous recounts of this species in various literary sources, even photographed captive specimens before, but not once have I seen this fish in situ. The beauty and brilliancy of this fish is indescribable, and none but a true ichthyophiliac can truly understand the intense excitement when I at length captured it. On filming this magnificent creature of clinquant beauty, my heart began to beat violently, the blood rushed to my head, and I felt much more like fainting than I have done when in apprehension of immediate death.

We subsequently saw another pair of adults, and a handful of juveniles all along the same depth range. This species is never common, occurring in scattered populations at depths in excess of 500ft. The species prefers to swim in pairs, although it can be taken singly from time to time. It is very weary, flighty and skittish, but should the collector require a specimen, it should be noted that cornering it along a steep wall proves to be very much effective in subduing it.

Gonioplectrus hispanus, The Spanish Flag. Here, a juvenile in captiity at the Toledo Zoo and Aquarium. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

The dispersal of the butterflies signaled the emergence of two Gonioplectrus hispanus, otherwise known as the Spanish Flag. Its uncanny resemblance to the state flag of Spain is reflected both in its scientific and colloquial epithet. The Spanish Flag is a beautiful grouper fond of deep waters. The species is rarely captured on the hook, where it is taken for human consumption. In the wild, the species is fairly common, but never abundant and sparsely distributed. G. hispanus possesses a pair of pelvic fins colored in a featureless powder pink, an unusual color for any fish species. When held erect, these fins look like a pair of butterflies wafting in the deep reefs.

A sinister force of malevolent intent was targeting one of the two Spanish Flags, in their effort to scoot away. An insidious tentacle lashed out, in futility, at one of the groupers. It was an octopus, and a big one at that. The cephalopod was guarding a cave, built upon a sandy slope in which a cluster of deep-water Caryophyllia corals were growing on. I asked Dutch if we could collect one of those polyps to photograph later on board the Chapman. He kindly obliged, and maneuvered the submersible to the little grove of coral.

The octopus, still leering from its cavern, was increasingly agitated at our unwelcomed presence. In a most shocking and astounding turn of events, it lashed at us, with all eight arms, and begun infiltrating our mechanical devices. It was visibly upset, and had every intention of chasing us away. In a battle between cephalopod and machine, it seemed hardly believable that we backed off, but it was relentless. Octopuses are not just gelatinous machines, rigidly programmed by their genetics. Instead, they are beings that, within the constraints of their molecular inheritance, make complex decisions and show every sign of enjoying a rich awareness. It eventually detached itself, but taunted a rematch should we go closer. We eventually left, devoid of coral, to the dismay of myself, but triumph of the octopus. Dutch managed to collect the coral from another site later on.

We had reached 650ft, the deepest point of our dive, but the Apricot Basslet was nowhere to be seen. Instead, a tall figure of sterling silver beckoned from behind a rock. Like sailors to sirens, we were captivated. Shimmering from a distance, it was striped in red. It took awhile to reveal itself, but there it floated, in all its glory, was Antigonia capros – The Deepbody Boarfish. Antigonia is a lesser-known genus from the family Caproidae. The genus and all its species are seen mostly from deep trawls as bycatch, making in situ footage extremely uncommon. This was the one and only Antigonia we saw in all our dives.

By now we had spent close to five hours in the submersible, and my bladder was yearning for some toiletry relief. Dutch decided it was just about time to head back too, so that was an astronomical sigh of relief for me (and my urinary system). The curasub had voiding bags, but I for sure did not want to go down in history as the one guy that had to pee in the curasub 600ft down in the ocean.

We made our ascent, slowly, and came to a huge looming boulder. Dutch had wanted to collect some hermit crabs and shells that were tacked onto this rock. It was easy pickings, but the base of the boulder had around it, a collection of loose rocks. I signaled for Dutch to disturb the area, and we were pleasantly greeted with a harem of Baldwinella vivanus. Lionfishes were plentiful too, but so were other charismatic serranids. We collected a few specimens of Baldwinella, which incidentally were named after Dr. Carol Baldwin of the Smithsonian Institution. The species was previously known as Hemanthias vivanus, but recent molecular work has relegated them to the newly erected genus Baldwinella. The males are breathtaking, and are uniform steely pink. The dorsal fin is characteristically enhanced by the extrapolation of the first five dorsal spines, giving it a cockatoo like appearance. The rest of the fins and face are lined with yellow.

Foetorepus sp. The size of the first dorsal fin indicates this might be a female specimen. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

Bruce and I had simultaneously spotted two little fish along a sand bank at 550ft. I, a dragonet species, and he, an unknown goby. Both were fairly easy to collect, and proved to be undescribed species. The dragonet was a member of the Foetorepus genus, but was small, and possibly in the female phase. The goby remains unknown. With our collection bucket now full of hermit crabs, shells and deep water fish, we made a quick ascent back to the surface, but not before stopping one last time at a promising looking ledge.

Bullisichthys caribbaeus. Its unique cranial morphology has earned it the colloquial name of Pugnose, or Bluntnose Bass. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

Lipogramma trilineatum. The specific epithet “trilineatum” is given in reference to the three stripes on the top of its head. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

Flushed out of hiding at 400ft were Bullisichthys caribbaeus, a small schooling species with a unique morphological quirk quite unlike any other. Aptly named the Pugnose, or Bluntnose Bass, B. caribbaeus is noted for having a flattened face with a prominent concavity on its nape, just above its upper lip. The fish is otherwise peach, with a constellation of silvery flecks strewn haphazardly across its body. Another little fish flushed from this ledge was Lipogramma trilineatum, and this is the fourth member of this genus that we’ve encountered in our dives so far. L. trilineatum is golden yellow, fading to mustard toward the posterior. The species is characteristic for possessing three scintillating blue lines (epithet: trilineatum) on its head. Like all Lipogramma, this species is very shy, and reaches a maximum length no longer than three inches.

After that last ledge inspection, Dutch made a beeline to the surface, where Joe and Manu intercepted at 130ft to collect the fish for decompression. By now I could see the surface and ambient light, much to the relieve of my highly distended bladder. We did not encounter any Apricot Basslets, but that disappointed was second priority to my desperate cry for urinary relief.

Back on the Chapman, Vanessa had returned from her day trip to Klein Curaçao, and had made a delicious sandwich. I made one too, and we shared stories of our morning. It turns out Klein Curaçao had much to offer, visually, and so I’ll be heading there the following morning. Vanessa was going in the curasub for the second leg after lunch, but I needed to lie down from the mental exhaustion that comes with fish geeking all morning. I don’t remember much, but I did have a really good sleep. When I woke up, four or five hours later, Vanessa had just returned, and of course, like a bad movie cliché, she saw Plectranthias garrupellus, The Apricot Basslet. Dutch had managed to collect a small number of them. What good luck for her!

That night we celebrated with wine and meat. Vanessa and Cristina were showing off their dancing skills. I had no idea what the dance was called. Tango maybe? Or Salsa perhaps. I have two left feet, and so I only dance when I’m mentally compromised. Joe was fishing for jacks, which had been attracted to the boat by the large number of baitfish, that were likewise attracted by the boat lights. The merrying continued through the night, and when Cristina and Katrina went to bed, Vanessa and I stayed up for a while longer looking at creatures of the night. The hull had attracted a soup of juvenile animals, one of which included a tiny octopus that I had netted. The commotion drew in reef squid, which were easily scooped up, like apples bobbing in water. Joe used the squid to catch a record breaking Jack, while I nibbled on leftovers, like a savage. Eh, safe to say it was really fresh. Like, still alive and moving fresh. Talk about ika sashimi.

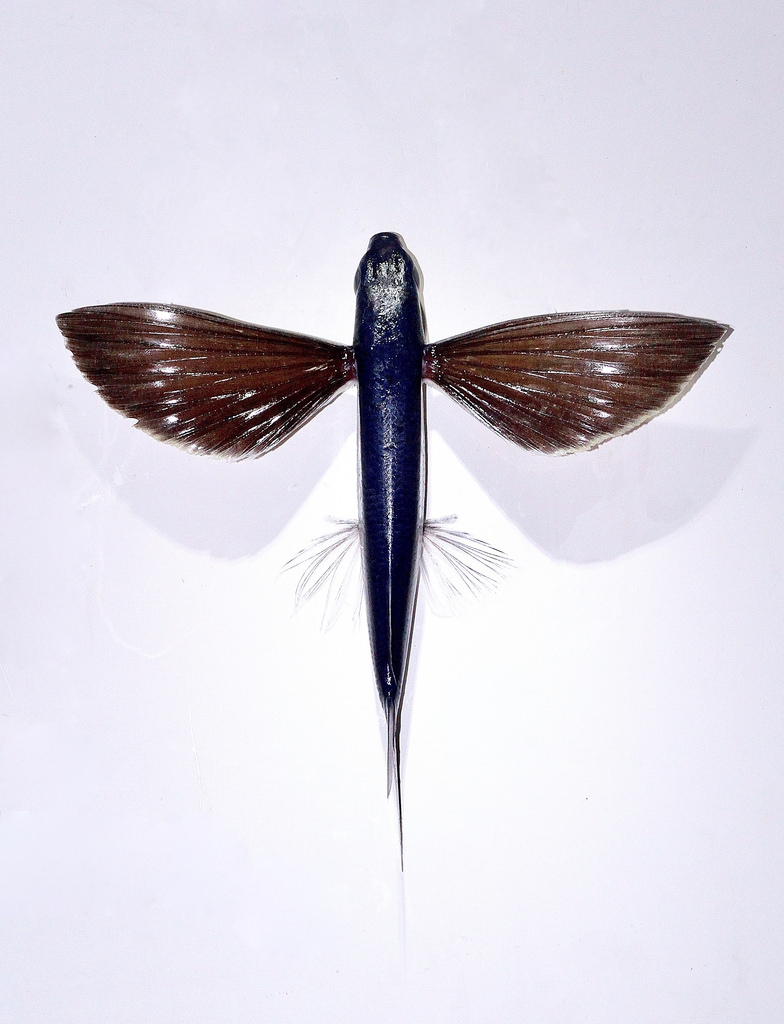

Just as I was about to head off to bed, I was stopped by a loud thud. A flying fish had, in its suicidal endeavor, landed on the deck in cold blood. I’ve always wanted to photograph one, so this seemed like a timely, serendipitous moment. It was a big fish, so finding a suitable background to lay it on was a challenge. Bruce’s white surfboard proved to be handy in this situation. Stiff from rigor mortis, the equally frustrating challenge of spreading its fins became immediately apparent. With no formalin on board the Chapman, we had to improvise. Vanessa strung the large, bird like pectoral fins with fishing line, and like a marionette, pulled them up. It was great, and I was able to photograph the fish with fins opened on a clean background.

It’s late into the night, and with all the shenanigans said and done, it was time to head to bed. I’m contented, to say the least, with my collection of photos and videos from today. Joe is still fishing on the deck. How he finds the energy is beyond me. I feel tired just watching him. And he gets up earlier than any of us. Tomorrow I’m going to explore the terrestrial land of Klein Curaçao. The spooky lighthouse sounds like fun, and I heard from Vanessa there’s a shipwreck on the beach too! But for now, my bed beckons. Kim Carnes’ “Betty Davis Eyes” is on repeat. The mood’s 1981 tonight.

0 Comments