It was assumed that routine cleaning of subs like Alvin after surfacing would take care of the bulk of the hitchhikers with the remainder killed due to depressurization as the sub rose to the surface after a dive. This, however, is not the case with at least one species of limpet, Lepetodrilus gordensis, as scientists have now learned.

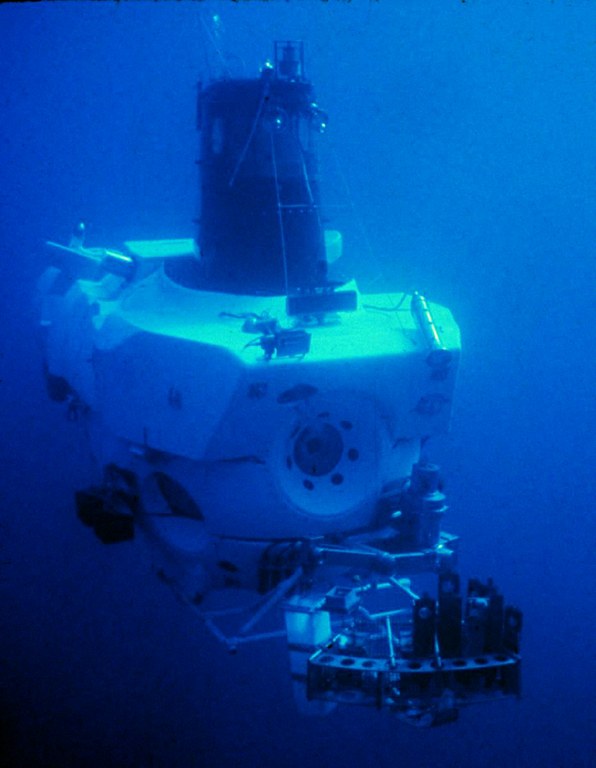

Scientists were using the Alvin submersible (pictured above) to sample hydrothermal vents at Gorda Ridge (depth 2.7 km), off the west coast of the United States. During their dive, they picked up a number of animal specimens in their sampling chambers including the limpet L. gordensis.

After surfacing late in the evening, the science team proceeded to clean Alvin per standard operating protocol. They cleaned the hull and sampling equipment and assumed that they had removed everything. If they missed something, they assumed that the depressurization from this dive and the repressurization of the upcoming dive would kill anything they missed.

They sailed 635 km in 30 hours to their next dive site: Endeavour Segment, Juan de Fuca Ridge, off the coast of Seattle, WA. There they dove 2.2 km to retrieve wood structures that were placed at Endeavour Segment 2 year prior. After securing the structures, the crew sampled the animals that were dislodged from the wood.

Once their dives were complete, the collected specimens were examined. What the scientists found surprised them. They again found the limpet L. gordensis, at the second dive site. What happened? L. gordensis is only known to live at Gorda Ridge. This second site does not even have the proper nutritional requirements for L. gordensis to survive. Did they find a new population that somehow found a way to survive in this environment or did they somehow have stowaways from the previous dive?

DNA testing was used to test the 16S gene of the limpets to determine if the samples were two separate populations or species from the same population. It turns out that they were from the same population indicating that they were hitchhikers from the previous dive. Apparently depressurization is not enough to kill Lepetodrilus – and possibly other deep sea life as well.

The scientists commented that “our small limpets and their associates accrued somewhere in the suction sampler, perhaps in the corrugated hose, where enough water pooled to keep them alive. Replacing the corrugated hose with a smooth hose may help prevent inadvertent transplants of biota, but any surface or crevice on the submersible or associated gear could provide refuge to macrofauna or bacteria. Spraying and flushing of gear by a member of the science party between dives is standard procedure, but in hindsight, may be insufficient.“

This paper was rather embarrassing for the scientists to write as it showed that their cleaning procedures and depressurization were not enough to stop cross-contamination. It was published, however, as a way to highlight the need for vigilance when visiting deep sea sites by submersibles.

[They] urge [their] colleagues to assume that physiologically tough stowaways are present on deep-sea research tools and to guard against transport of non-native species by clearing hoses and rinsing containers with freshwater, or even a peroxide solution, and drying tools before transporting them to different sites. Such measures may be especially important when working near marine reserves, such as Endeavour Hydrothermal Vents Marine Protected Area (Dando & Juniper 2001). Even when science operations are nonbiological, inadvertent collection of biota is likely, perhaps even unavoidable. The biological consequences of working with subsea vehicles are still being determined, and best practices are still being developed. Preventing introductions is of paramount importance in maintaining intact hydrothermal vent ecosystems.

(via BBC, Conservation Biology)

0 Comments