Nuptial P. ignitus in the Maldives. Credit: asino48

The genus Pseudanthias, known commonly as fairy basslets, is a diverse group of colorful schooling reef fishes popular amongst aquarists. It has traditionally been split into three subgenera—Franzia, Mirolabrichthys, and Pseudanthias sensu stricto—based on differences in caudal fin shape, fin scalation, opercular spines and lip enlargement. This article will endeavor to review the classification and phylogeny of Mirolabrichthys, but before doing so we must understand what characters diagnose this group. This, it turns out, is a particularly vexing question to answer.

Mirolabrichthys tuka and M. pascalus were described in 1927 as a new genus and species of anthiine basslet, based on possessing two (instead of three) opercular spines, as well as an unusually elongate and fleshly extension of the upper lip of males. Later additions to the genus—dispar, lori, bicolor—differed dramatically in many ways from from tuka and pascalus but were included because of a similarly enlarged lip and their comparably elongated body and deeply-forked caudal fin.

Comparing relative position of dorsal, pelvic and pectoral fin bases in the four major clades.

When Randall & Lubbock revised Mirolabrichthys in 1981—treating it as a subgenus and adding five more species in the process—the characters originally used to define it had become completely unreliable. The reduced opercular spine count was now highly inconsistent, and, while most species possessed the enlarged upper lip, not all did. Given the wide range in many meristic measurements, there is little reason to assume that the shape of the upper lip didn’t evolve independently in multiple lineages. What all these species seem to share in common is an unusually streamlined gestalt, and it would only make sense that any fairy basslet evolving in this direction would converge upon a similar hydrodynamically-shaped upper lip.

To this day, there has yet to be a published phylogeny for this group, either morphological or molecular. The various species (of which there are at least twenty) can be placed with relative ease into lineages recognized by coloration and meristics, but the evolutionary relationships between these clades are particularly intractable without any published molecular data. I personally see little reason to believe that this assemblage of species forms a single group. Rather, three easily diagnosed clades emerge, which may or may not be deserving of generic status. The question that needs answering is where do these three clades derive from. Did they all evolve from a single branch within Pseudanthias? Or, as seems most plausible to me, did they evolve from separate branches of Pseudanthias or, perhaps, even from outside of this genus. If such is the case, we may one day see Mirolabrichthys and Nemanthias (in an expanded sense) as valid genera.

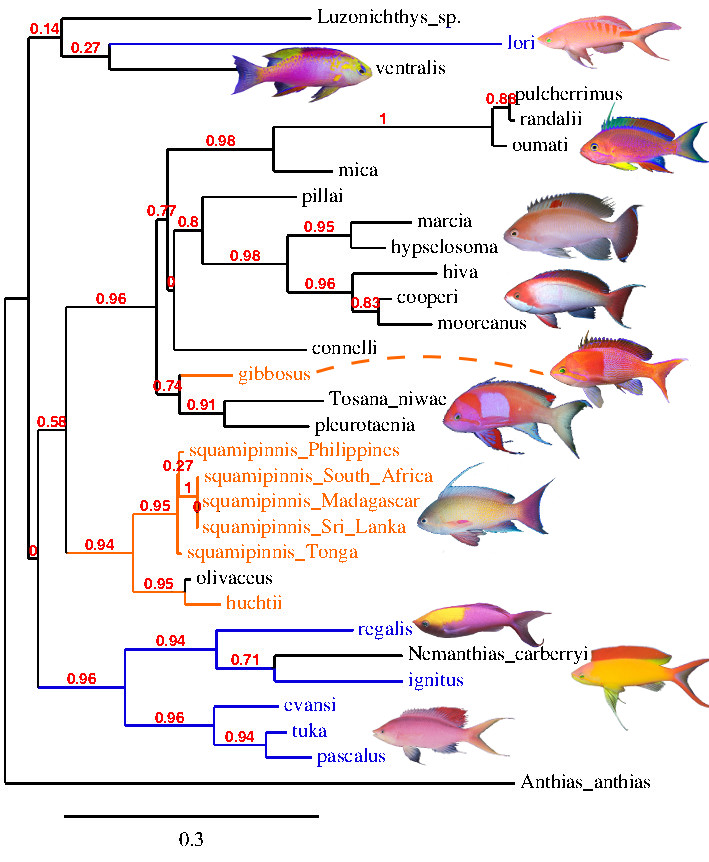

Phylogeny from cytochrome oxidase 1 (genbank). Note that Mirolabrichthys (blue) is not monophyletic.

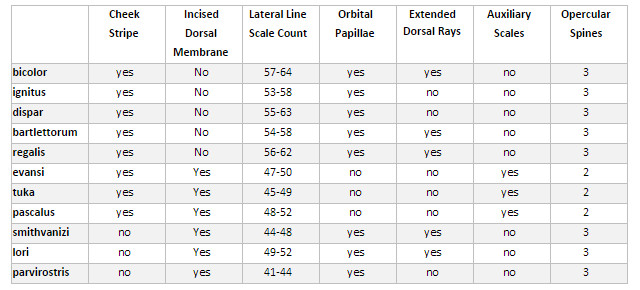

The phylogenetic trees used in this article are a best guess based on previously published morphological and CO1 data, biogeography, coloration and my own whims. When assessing phylogenetic relationships, it is important to find identifying characters that readily differentiate species and groups of species, and then to find the most parsimonious way to organize that data. Of particular importance are characters that are indicative of the true evolutionary history of the group, and not ones that merely arrange things conveniently. One possible character of use is the orange stripe that descends posteroventrally from the upper lip, through the eye, and along the cheek. Nearly all species of Franzia and Pseudanthias s.s. possess this stripe, but only a portion of Mirolabrichthys do. From this we can infer that those Mirolabrichthys lacking the cheek stripe likely form a single (monophyletic) group. We can corroborate this assumption by comparing other morphological features to the striped and unstriped groups.

Table 1. Comparing select Mirolabrichthys characters. Modified from Randall & Lubbock 1981.

0 Comments