An unusual behavior in stony corals has just been documented for what might be the first time—swimming. The video seen below was recently shared by the Numazu Deep Sea Aquarium and shows a solitary azooxanthellate scleractinian (Flabellum deludens) gently floating about in its aquarium. To accomplish this feat of positive buoyancy, the coral has massively inflated its tissues with water, turning itself into a cnidarian dirigible of sorts.

The question raised by this intriguing observation is whether or not we’re witnessing a natural behavior used in the wild, or is this merely an artifact of it being kept in captivity? It’s not hard to imagine how a sessile creature like this would benefit from having an escape mechanism at its disposal. It’s possible this might be an effective tactic for avoiding some of the slow-moving predators which are likely to prey upon it in the wild, like snails and sea stars. It remains to be seen how quickly Flabellum can actually inflate itself to achieve these hydronautical feats. If it takes the better part of a day to become sufficiently buoyant, it might not be of much use against a swift-footed echinoderm, but perhaps against a weaker gastropod foe this strategy works.

There are other free-living solitary corals to be found in the deep sea, and it’s quite possible that some of these employ similar methods. The closest relatives of Flabellum are generally found attached to solid substrates, with the exception of the familiar aquarium coral Rhizotrochus. Though it can certainly expand its tissue to a fair degree, Rhizotrochus possesses a more robust skeleton which is anchored into soft sediments with a series of rootlike growths and is thus unlikely to ever lift off from the ocean floor. The closely related Truncatoflabellum is a better candidate, but observations are lacking.

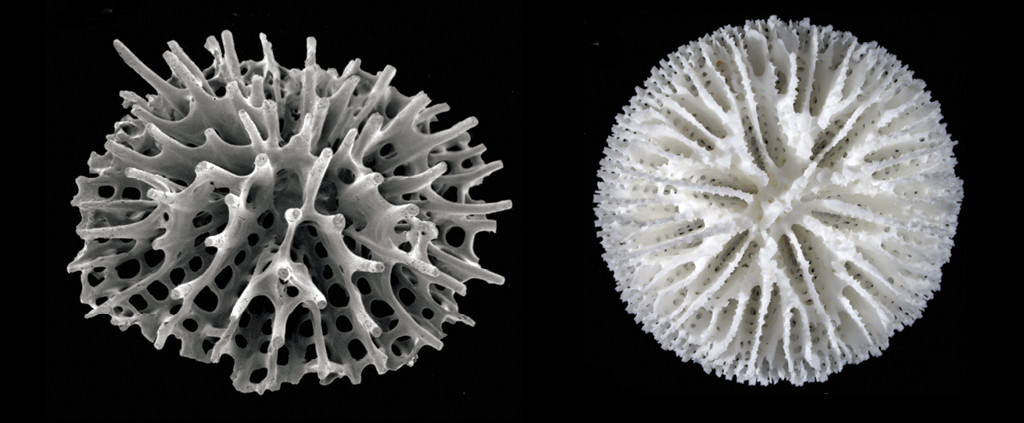

Micrabaciids, like these Leptopenus and Stephanophyllia, are probably light and airy enough to float. Credit: Cairns & Kitahara 2012

Caryophyllids and dendrophyllids—two of the more diverse families of azooxanthellate stony coral—are generally attached and denser in construction. There are several turbinoliids with a similar conical morphology, but this group is seemingly adapted for burrowing into sediments, as is the distantly related Deltocyathus. Probably the best place to look for motile corals is among the small and ancient family Micrabaciidae, whose handful of species have gossamer skeletons fully surrounded by an expansive tissue. Unfortunately, photographs of these animals alive are almost non-existent, but perhaps somewhere in the ocean’s inky darkness they gracefully swim about.

0 Comments