Given how many dangerous creatures are readily available in the aquarium industry, it’s easy to think that aquarists might have a tendency towards masochism. There are potentially lethal corals (Palythoa cf toxica)… there are potentially lethal urchins… there are potentially lethal fishes… and an anemone that can inflict nasty ulcerative scars. Not to mention all the other venomous fishes and corals which we barely bat a lash at. But there is one dangerous organism which hardly anyone has heard of and which does occasionally sneak into our reef tanks—the “iramo”.

A pair of large colonies of iramo in Japan. The colony on the right has retracted its tissue, exposing the white underside. Credit: Kushimoto Marine Park

Now, I use the term “coral” loosely here, as this animal is very coral-like, but it is most definitely not a coral in the common sense. Recall that corals are part of a diverse lot known as the Anthozoa, which is in turn comprised of smaller subgroups, such as the sea anemones, corallimorphs, soft corals and stony corals. All of these anthozoan groups share a couple of important features: 1) there is never a medusa stage to the life cycle (i.e. corals never mature into a “jellyfish”) 2) the body has either a 6-fold or 8-fold radial symmetry (vs. 4-fold in other groups). This little zoology lesson is important when we consider the iramo, which looks remarkably like an anthozoan coral but, upon closer examination, shows itself to actually be a scyphozoan—one of the true jellies.

An aquarium specimen, which spread to form numerous satellite colonies throughout this tank. Credit: たらふく

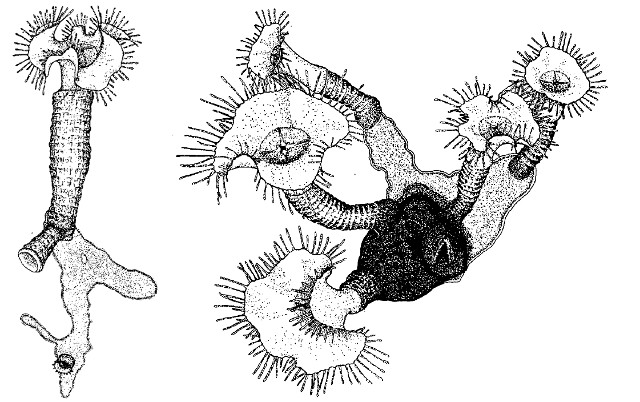

Scyphozoans are a rare commodity in the reef tank, and the iramo and its ilk are perhaps the only member of this diverse group to regularly hitchhike into our aquaria. They do so during the polyp stage of their life cycle (known as the scyphistoma), eventually maturing into teeny, tiny jellies through the process of strobilation—you may have seen these stuck against the glass when you first set up your reef tank, though they tend to disappear within a few weeks.

Another aquarium colony, form the same tank as the previous image. Seen here next to Briareum. Credit: たらふく

Taxonomically, there has been some historical confusion in matching these polyps (classified under the name Stephanoscyphus) to the mature medusae (Nausithoe). Early aquarium studies eventually allowed for the observation of the complete life history, confirming that Stephanoscyphus develops into Nausithoe, thus relegating the former taxon into the dustbin of history. But, even today, similar scyphistomae that remain unmatched to their medusa are provisionally classified as Stephanoscyphistoma. And, yes, that is some terribly polysyllabic nomenclature right there, but it beautifully translates from the Greek for “crowned cup mouth”, in obvious reference to the gross morphology here.

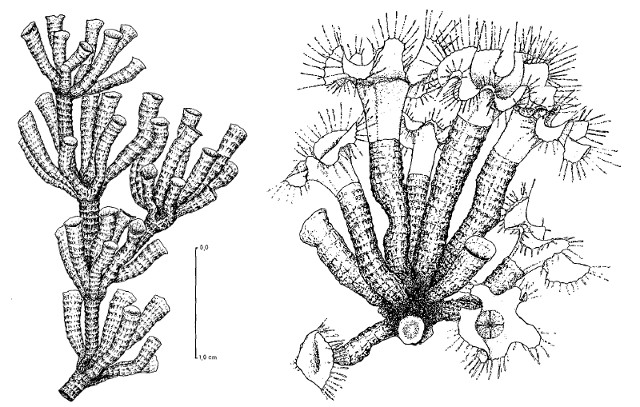

The iramo (Nausithoe racemosa) represents a highly unorthodox type of colonial scyphistoma, which can potentially live for many years, spreading and growing to roughly 20cm across. It belongs to a small group of jellies which have polyps encased within a chitinous tube (the “periderm”), classified as the Order Coronatae or the coronate jellies. This semi-rigid tube gives a very coral-like appearance, further accentuated by virtue of the fact that the iramo is also zooxanthellate (i.e. photosynthetic). Essentially, this is a jellyfish coral!

It can be difficult to understand quite what is going on here morphologically just by looking at photos of whole colonies, as the polyps (i.e. the individual scyphistomae) are quite small (just a couple millimeters in diameter across the peridermal tube) and densely arrayed. Uniquely in N. racemosa, the polyps can form highly convoluted branching patterns, with the oral discs being larger and more-convoluted than in related species. This gives an appearance not so unlike what we see in certain “brain corals” or a large colony of Palythoa grandis, though there is also a resemblance to certain types of macroalgae, such as Padina or Lobophora (giving rise to another common name, “stinging algae”). Related species show the same general morphology, but occur either as solitary polyps or loosely interconnected colonies.

As a zooxanthellate pseudo-coral, the iramo is a species which can be readily grown and cultivated in captivity. Aquarium studies have shown that severing a single scyphistoma quickly results in the formation of a new colony in the same manner one might frag an Acropora. The open end of the peridermal tube is said to leak out into a thin mat of tissue (the “scyphorhiza”) sprouting new polyps, eventually becoming overgrown by a new periderm. In this manner, a single colony can quickly and easily be fragged into a large number of specimens.

An apparently undescribed species of Synalpheus snapping shrimp frequently associated with iramo. Credit: kiss2sea & manboon

Large colonies have been observed, albeit rarely, in reef tanks, and this is cause for some concern, as this species is known to harbor a pretty nasty sting. I’m not aware of any aquarium related injuries (though I’m sure these have occurred), but diver encounters have resulted in some pretty horrendous looking blisters and ulcerative scars that take weeks to heal. The pain and itching is said to last just as long, and, when stings occur on the hands, significant pain in the joints is another fun symptom. The pictures are pretty gruesome, so I’ll just link to them (here, here, here, and here). There are even medical reports of systemic reactions which could likely pose life-threatening symptoms if not treated quickly. In total, this is not an organism you want to get too close to.

Though, the question must be asked, is there a place for the iramo in the aquarium industry? This is truly a unique and fascinating creature, quite calliphoric in its own way, and perfect for those looking to add a different kind of diversity to their aquatic menagerie. And, it’s not like there isn’t already a profusion of species in this hobby that are just as dangerous, some even moreso. The iramo is reported to be quite commonly encountered in parts of Japan, as well as other aquarium collecting regions (e.g. Guam, Kwajalein), so perhaps it’s time for some intrepid mariculturist to take a stab at propagating it. A bushy colony of jellyfish coral is just the kind of invertebrate sui generis I’d love to add my home tank. But, remember—you can look, but don’t touch!

Hi,

i have a colony of this animals in my tank.

Came as a hitch hiker on a frag stone…

Is still growing after years, and i have given some away for research and public aquariums.

Brought my to hospital, after contact, hand inside was no problem, but between the fingers it was itching within seconds.

Got red spots, and necrosis, was leading to lymphangitis after 2 days and needed to be treatend with strong antibiotics. After 3 days i left the hospital, and the lower amount of antibiotics let it come back…. So stronger dosis and after a week it was ok.

Easy to id, will quickly change from brown / green to white when disturbed…

Regards,

Wolfgang https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/d0d72812e068b037e7bb538fe9eb48b7f7d4d5fc3a5fb0ddcd2d7db5ddeba5ab.jpg https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/63f64077069cfd21a282703bd6a0aa3468304f18333fdd8ed1ddd5cdb390335d.jpg