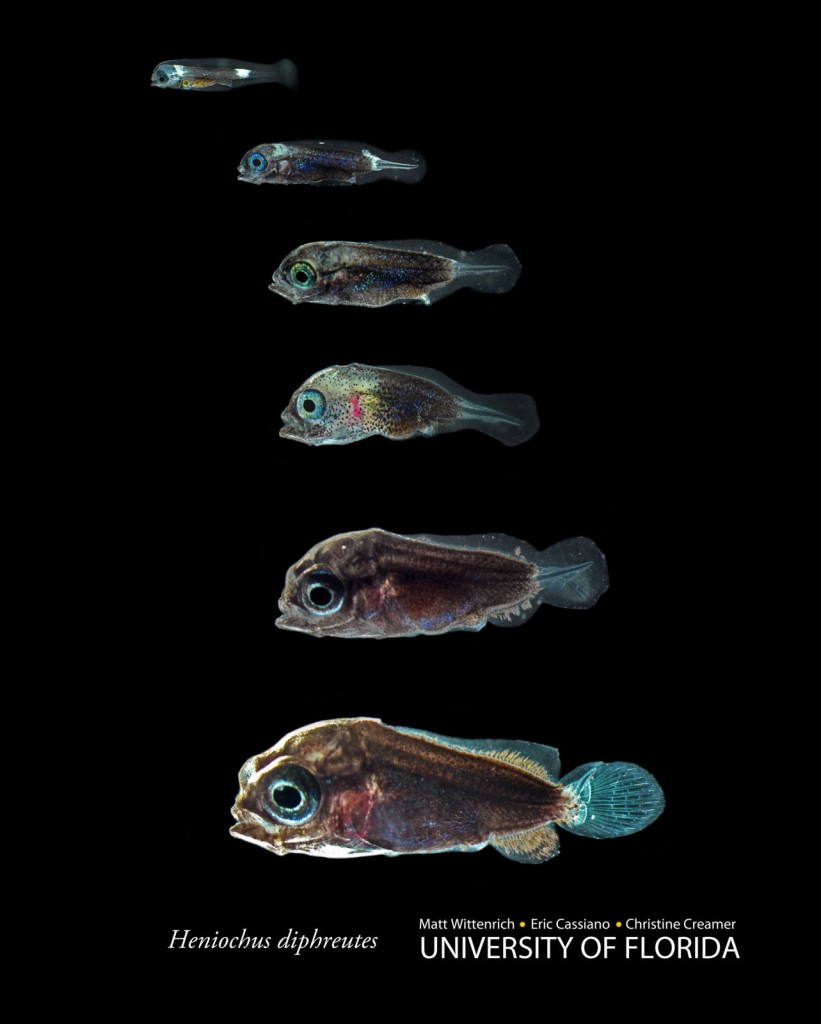

This isn’t the first time that a Rising Tide organized cross-institutional collaborative breeding project has grabbed headlines this year, but this may be the biggest proof-of-concept to-date. The image above shows the larval development of Heniochus diphreutes, the Schooling Bannerfish, to 37 days post hatch. These larval images were made possible through the very special collaboration between University of Florida’s Tropical Aquaculture Lab, and other members of the Rising Tide Conservation Initiative – in this particular instance the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium. This early success finds the collective effort knocking at the door, attempting to cross the threshold to the first captive-bred Butterflyfish.

To date, the Rising Tide Conservation Initiative has developed egg collectors that were deployed to a myriad of public and private aquariums. These collectors trap the buoyant eggs of pelagic spawning fishes. However, because these eggs are harvested from aquariums housing numerous species, and because spawning may not actually be observed, there has been a lot of guesswork involved. The methodology applied to these eggs is somewhat a shotgun approach of applying known rearing techniques to the eggs and seeing what develops. DNA analysis also helps identify mystery eggs and larvae. This further helps collaborators build a catalog of eggs and larva that can be used to readily identify the same in future collections and rearing attempts.

Paul Rinehart and Ramon Villaverde of the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium used such a larval collector to trap eggs from their aquaria. Dr. Wittenrich described the egg shipment process in some detail on the Rising Tide Blog. “They collected about 9 mL of eggs, about 300,000 eggs. They transferred the good eggs into fresh clean seawater after charging it with pure oxygen. The bags were then closed up with no air space to avoid unnecessary splashing as the box was shipped since we thought this could potentially damage the delicate eggs and larvae. The styrofoam box was packed up and shipped FedEx priority overnight.”

If you take nothing else away from this article, realize that Rising Tide has just disclosed a very important methodology for shipping the viable eggs of reef fish over a thousand miles. This is no small feat; realize that at times, it seems that a simple change of a degree or two in temperature may be all it takes to kill off the eggs of a pelagic-spawning marine fish. Still, if you’re willing to pay for the Fed Ex shipment, you now have a methodology to try to get fish eggs from anyone who is spawning them, to anyone who is rearing them. Rising Tide isn’t the only group of collaborators tinkering with the shipment of fish eggs – ORA and LiveAquaria recently announced their own successes with the collaborative breeding of Amphiprion mccullochi.

The successful transfer of eggs from one facility to another, while interesting itself, isn’t the only story here. Every aspect of this project is another step into the relative unknown. Dr. Wittenrich is the first to tell you that it’s not him, but an entire team, who come together to tackle the experimental rearing that takes place at U of F’s Tropical Aquaculture Lab. As noted above, both Eric Cassiano and Christine Creamer deserve recognition of the accomplishments with Heniochus larva.

Eric Cassiano releasing eggs and larvae into the rearing tank after acclimation. Image courtesy Wittenrich

It quickly becomes apparent that the efforts at the Tropical Aquaculture Lab are continuing to prove the value of dynamic rearing environments. Specifically, Wittenrich goes to great lengths to again describe what can be summed up as using current gradients and light gradients in the rearing environment. By providing variable amounts of current and light throughout the rearing container, the larval marine fish are able to find the exact amount of current, and light intensity, that’s optimal for feeding. This is why marine breeders are continuing to shift towards the black-round-tub, or BRT, as the modern rearing vessel of choice for the home hobbyist. I’ve applied this methodology and seen the results numerous times in my own breeding, and strongly encourage would-be marine fish breeders to examine the concepts further further.

Feeding of unknown larvae is a daunting task as well. Ironically, I remember the days when we’d say that the feeding of wild-collected, size-sorted plankton was cheating. In some respects, it might actually be cheating as wild plankton does represent a tool that is fundamentally unavailable to the inland marine breeder. However, when it comes to cracking the code of a new larval fish, Dr. Wittenrich has decidedly proven the efficacy of using wild plankton to determine what, if anything, the larval fish will consume. When it comes to the larval Heniochus, once again, it appears that copepods made up the bulk of accepted foods.

Dr. Wittenrich inspecting and feeding larval Heniochus - note the black round tubs and linear light source that create current and light gradients. Image courtesy Wittenrich.

Based on the larval structure and development, it is safe to say that indeed, this project came close to success on the very first try. The main bottleneck in rearing actually occured later in the larval phase, with the tholichthys larval stage that consists of bony plating and armor – unique to the Butterflyfish family. With the last larvae dying at 41 days post spawn, we can only hope that it only takes another couple attempts to make the dream of a captive-bred Butterflyfish a reality.

It bears repeating that were it not for the collaborative vision set up by the Rising Tide Conservation Initiative, this project would not have occurred. It is yet another resounding example of how “open source breeding”, that is to say working together and sharing, can bring real discovery and innovation to the table. We strongly encourage you to read the complete, detailed story so far, on the Rising Tide Blog, and we anxiously await the results of the next rearing attempts at the U of F Tropical Aquaculture Lab. Good luck Rising Tide!

Show-offs! 😉

Great article! It’s always great to see new species being tackled, but those are some ugly babies.