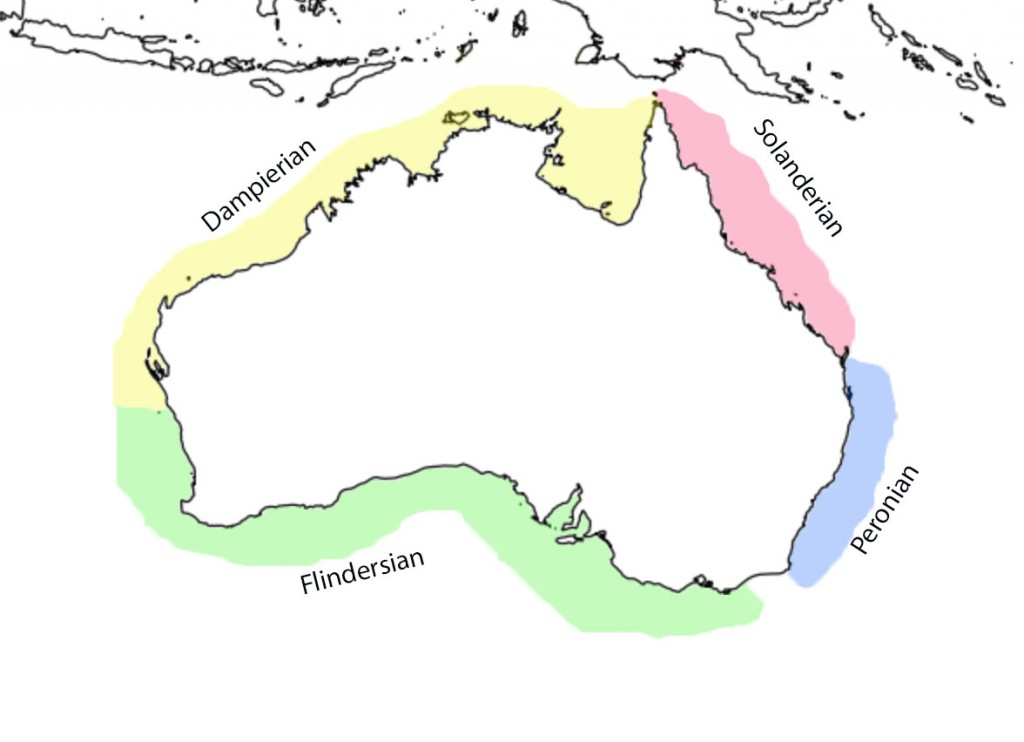

Biogeography of Chelmon and its sister genus Chelmonops. The two genera display a distirbution encompassing the four biogeographic regions of Australia, namely the Dampierian, Solanderian, Peronian and Flindersian regions, which, in a clockwise direction starting from the Torres Strait, make up the four coastal quadrants of this continent. Photo credit: Phillip Colla, digital-reefs, Michael Moye, Brian Mayes and John Randall.

The extremely diverse Chaetodontidae is home to a plethora of butterflyfish species, of which, a large majority are charismatic, colorful, iconic piscines that are largely coral reef associated. The family houses ten or so genera, and, despite being one of the most well studied groups of fish (having even received an extensive molecular based phylogenetic review), remains plagued with several taxonomic conundrums and inconsistencies. For one, the genus Parachaetodon is shown to be nestled within Chaetodon, and so the former genus ought to be relegated as defunct. However, the species, Parachaetodon ocellatus, cannot retain its specific epithet in Chaetodon, as Chaetodon ocellatus is already taken by an Atlantic species prior to this change in name. It thus takes the next available name – oligacanthus. Despite having strong genetic and molecular support in the transfer and renaming, the move is still not widely accepted by the general populace, and so the species now masquerades under two different aliases – Parachaetodon ocellatus and Chaetodon oligacanthus. This, depending on your taxonomic stand, leaves Chaetodontidae with either ten or eleven genera.

In addition to being highly speciose, butterflyfishes are also aggressively distributed, attaining their maximum diversity in all warm, tropical waters of the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic Oceans. A few species are found in the subtropics, where they swim undeterred by cold water. On top of their dominating presence on the reefs, chaetodontids also display great success in conquering various habitats, of which, nearly all can be found with a resident butterflyfish species. These include sun-spangled coral gardens, to bone crushing mesophotic reefs, to silty, visibly poor coastal shorelines replete with freshwater runoffs.

And, in addition to displaying this impressive adaptability, chaetodontids have also evolved numerous characteristics that enable their success in obtaining food in their specific domains. Hemitaurichthys, for example, have evolved to feed almost exclusively on zooplankton, in which they seek out by swimming in large shoals high above the calcareous benthos. The triangulum, speculum and ornatus groups of the genus Chaetodon, on the other hand, obtain their energy from coral polyps, in which they feed almost exclusively on. Not even the noxious chemicals in soft corals can deter butterflyfish, and here, the melannotus group displays great skill and craft in the adoption of this dietary preference.

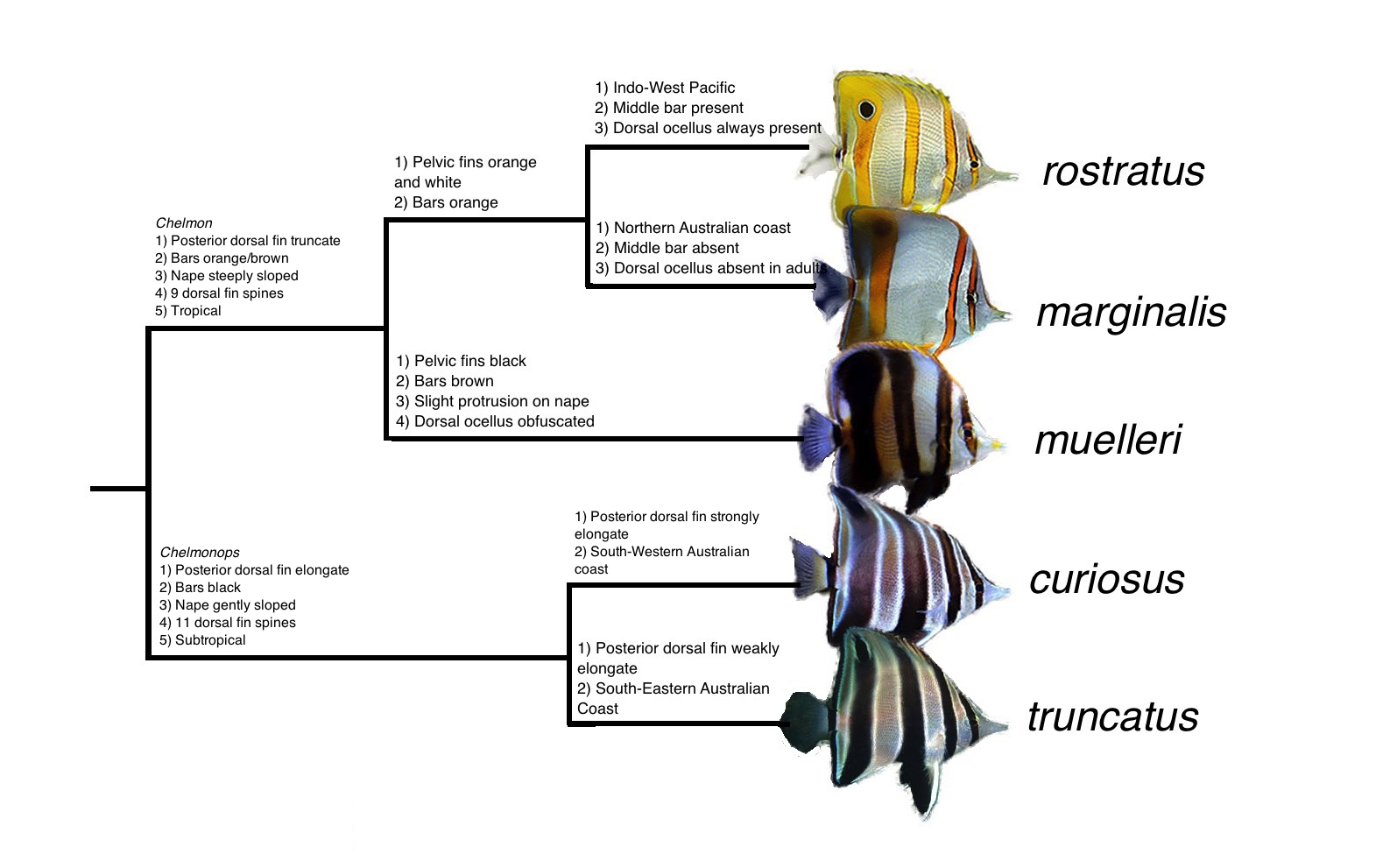

The phylogenetic relationship (Bellwood et al.) of the genus Chelmon and its sister genus Chelmonops. Photo credit: Phillip Colla, digital-reefs, Michael Moye, Lemon TYK and Fishes of Australia.

Even more spectacular still are the species that feed not on coral, not on zooplankton, but instead, on polychaete worms, echinoderm tube feet and other benthic micro invertebrates. Because of the specificity in their dietary preference, these butterflyfishes have evolved long, slender mouthparts that are perfectly designed for poking into small cracks, holes and other similar structures in search of food. The “long-nosed” butterflyfishes are some of the most morphologically quirky members of the family, and in this three part review, we take a look at some of these representatives in the genera Chelmon, Chelmonops, Forcipiger and Prognathodes.

Chelmon and Chelmonops form a sister clade representing six species, of which five are strictly endemic to continental Australia. Like many fishes inhabiting this region, the various species show disparate distribution patterns based on Australia’s unique biogeography. In general, biodiversity patterns are different on the Western and Eastern coasts, in which there are four general regions, each occupying the four quadrants of Australia’s boundary. (Hedley 1904) designated the northern coast as the Dampierian and Solanderian regions respectively. The Dampierian region is defined as the region between the Torres Straits west to the Houtman Abrolhos, and the Solanderian from the Torres Strait east to Queensland. Conversely, the Flindersian region (Cotton 1930) is defined as the region stretching from Geraldton, Western Australia, to the New South Whales-Victorian border including Tasmania. The Peronian region encompasses the southeastern coast of Australia, from Queensland to Tasmania. There has been a lot of study on Australia’s biogeography, and in this article we won’t be delving too much into it. However, it is useful to keep this in mind as we explore the biogeography of Chelmon and Chelmonops.

A typical haunt for Chelmon species. These shallow, tidal pools are often home to stranded juveniles. Because of the fluctuating sea levels, as well as the occasional nearby freshwater runoffs, Chelmon butterflyfishes are often exposed to drastic salinity swings.

Both genera are superficially similar, but Chelmon differ in being almost entirely tropical, only rarely straying south of the Tropic of Capricorn. Chelmonops, on the other hand, is strictly subtropical, found below the Tropic of Capricorn on the southwestern and southeastern Australian coasts. The two genera mix at the contact zones. They are also meristically different, with Chelmon possessing six dorsal spines, and Chelmonops with eleven. Both genera, however, are similar in their habitat preference. Unlike most Chaetodontids, these butterflyfishes are nearly always found in shallow inshore reefs, sometimes even near estuaries and mangroves with significant freshwater runoff. In Singapore, Chelmon rostratus is not uncommonly found near beaches and jetties, where juveniles can be found in seagrass beds or beneath yacht decks and pylons.

Chelmon muelleri and C. marginalis, likewise, share the same habitat in Australia, where they can be found stranded in shallow tide pools and sea grass beds. This murky, visibly poor water is often shared with the angelfish genus Chaetodontoplus, especially C. mesoleucus in the Indo-West Pacific and C. duboulayi and C. meredithi in Australia. The same habitat preference applies to Chelmonops.

Chelmon

Chelmon is a genus I hold near and dear to my heart. C. marginalis and C. rostratus have had a direct influence in igniting what would soon be an insatiable fire for my love of marine fish. The genus holds three species, of which C. rostratus is the most widespread. The other two members are restricted to the tropical coasts of Australia in the southern hemisphere. All three species are sympatric in the northern Coral Sea, but hybridization has not yet been reliably documented in Chelmon (although it is likely to occur). Chelmon is easily diagnosed by their orange vertical banding (brown in muelleri) and distinctive body shape. All species possess a dorsal fin ocellus in their juvenile stages, which, with the exception of C. marginalis, is kept to adulthood.

As mentioned in the introduction, Chelmon are fond of coastal reefs with high turbidity. They are often encountered during low tides, where juveniles can be found stranded in rock pools and exposed reefs. Despite their preference for these somewhat harsh conditions, all members of Chelmon are somewhat delicate and fare rather poorly in captivity, where they often fail to eat and thrive. Feeding responses can be elicited with live worms, which in the wild, make up a significant portion of their diet.

Chelmon rostratus – The Copperband Butterflyfish

Juvenile Chelmon rostratus stranded in a shallow coastal reef of Singapore during low tide. This is a common sight and preferred habitat for the species. Photo credit: Wild Singapore.

Chelmon rostratus is the commonest and most widespread species in this clade. In this beautiful butterflyfish, the ground coloration is silver with numerous fine horizontal blue striae. This is usually only noticeable in larger specimens under close scrutiny. The body is decorated with four prominent coppery orange bands, with the first one concealing the eye. A large blue-ringed ocellus is present on the posterior soft dorsal fin. The pelvic fins are yellow-orange with a white central region. This iconic species is unmistakable, and is very aptly known by its common name – The Copperband Butterflyfish.

C. rostratus is a familiar sight in Southeast Asia, where it occurs commonly in beaches and shallow coastal shorelines. It is often caught accidentally in fish traps, where it suffers the unfortunate fate of inevitable death. C. rostratus is distributed from Ogasawara south to Taiwan, the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia. It spreads northwest to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The species can also be found east to Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. It reaches its southernmost limit in Queensland Australia, but juveniles sometimes show up in Sydney and New South Whales as rare, tropical waifs. They never survive the winter here, and are therefore only considered resident in the northern territory above the Tropic of Capricorn. In the Northern Coral Sea, it overlaps with its sister, C. marginalis, as well as C. muelleri.

Why this species adopts such a prevalent distribution in the Indo-West Pacific is somewhat of a curiosity, especially considering that the other two members of its genus are strictly endemic to the coastline of Northern Australia. The epicenter of Chelmon diversity is quite likely to have originated here in the southern hemisphere. Perhaps this species has managed to push north, where it has since radiated across the Indo-West Pacific.

Chelmon rostratus in a typical turbid coastal reef of Pulau Hantu, Singapore. Photo credit: The Hantu Blog.

C. rostratus is exceedingly common in the trade, and is not expensive. In places like Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia, local fishermen regard this as a nuisance species, where it holds no commercial value. This species is sensitive, and its ability to thrive in captivity is almost directly correlated to the collection, handling and holding practices that it receives. Specimens hailing from Indonesia are almost always doomed to die, while those collected in Australia exhibit a markedly disproportionate survival rate. Its mouth is slender and well suited for picking at worms and other benthic invertebrates, and as such, makes for a reef safe butterflyfish. There are, however, stories of this species eating coral polyps in captivity, but these are often few and far between.

An unusual individual from Raja Ampat, Indonesia with an incomplete middle band. Note the stark similarity to Chelmon marginalis. It can also be noted to possess intermediate phenotypes between the two species, but C. marginalis is unlikely to waif so far north into Raja Ampat. This likely represents an isolated, cryptic population of C. rostratus. Photo credit: David Rolla.

For a species so widely prevalent in the Indo-West Pacific, it is quite remarkable that Chelmon rostratus is able to maintain, to a large extent, its phenotypic homogeneity. The species makes an exception to this in the isolated regions of Raja Ampat in West Papua. This region is a well regarded hotbed of speciation, in large due to its geographic isolation from the surrounding waters. Another chaetodontid example is seen in Forcipiger wanai, which will be elaborated ad nauseum in the following article. That, as well as an in-depth look at the biogeographical history and how the isolating factors come into play in this region.

C. rostratus from Raja Ampat sports a somewhat vestigial middle band, somewhat reminiscent of Chelmon marginalis. While the phenotype resembles a probably hybrid of these two sisters, the latter species is unable to cross this far north. This may not be entirely implausible, as there have been unconfirmed reports of C. muelleri here. However, these are unsubstantiated, and in all likelihood, represents erroneous sightings of C. rostratus instead. Whether or not the vestigial banded populations here differ genetically from the more widespread population is unknown, but with all respect to its allopatric isolation, it, at least, should be worthy or further study as a possible cryptic representation of C. rostratus.

Chelmon marginalis – The Margined Coralfish

Chelmon marginalis in captivity. Note the vestigial middle band and the fading dorsal ocellus. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

Chelmon marginalis is the sister counterpart of the preceding species. The markings are essentially the same, but in C. marginalis, the middle band is either vestigial, or completely absent. In juveniles, this band is present as a fuliginous, sooty manifestation, and fades away quickly as the fish matures. The dorsal ocellus is strongly present in younglings, but fades away slowly with age before completely disappearing in the largest of adults. The epithet “marginalis” therefore refers to the stripes being present only on the marginal edges of the fish.

Like C. rostratus, C. marginalis is fond of turbid, shallow water in inward reefs. It adopts a mostly Dampierian distribution on the northwestern cost, tracing the shoreline from Geraldton in Western Australia to the Torres Strait. It very weakly crosses the strait into the Northern Coral Sea, where it reaches its distribution limit. It overlaps with C. muelleri significantly in the northern coast, and weakly with C. rostratus in the Coral Sea.

Because C. marginalis is only collected from Australia, where practices are considerably more favorable, the species is significantly hardier and more robust than C. rostratus. Although uncommon in the trade, it cannot be considered rare, and can be obtained from time to time at fairly reasonable prices.

A fully grown C. marginalis in Ningaloo Reef without the dorsal ocellus and middle band. Photo credit: John Turnbull.

Chelmon muelleri – Mueller’s Coralfish

Chelmon muelleri in captivity. Note the extensively shaded posterior half, giving the fish an almost bicolored appearance. This is variable, and in some specimens, the extensive shading is not present. Also note the bump on the nape. Photo credit: Ohm Pavaphon.

Chelmon muelleri sits at the unfortunate receiving end of unjust hate and disdain. Often considered the ugly duckling of the genus, C. muelleri is the least encountered member of the genus Chelmon. In this species, the ground coloration is of the usual silvery-grey, but the bands are russet brown instead of orange. The second and third bands are often skewed slightly, where they then converge at the base of the pelvic fins. Unlike the phenotypically consistent C. rostratus and C. marginalis, C. muelleri adopts unusual variability in its appearance. The posterior half ranges from cleanly banded, as with C. rostratus, to heavily shaded such that the usual bands are completely obfuscated. These forms represent the two extremes, and the gap is filled with a spectrum of intermediates with various intensities of shading. Unlike the other two species, the pelvic fins of C. muelleri are entirely black.

The usual dorsal fin ocellus is present throughout its life, but this is usually hidden by the dark shading of the posterior banding. In addition, large specimens possess a protruding fleshy bump on the nape. These unusual characteristics likely correlate to its placement as the basal most species in the phylogeny of Chelmon.

C. muelleri is distributed on Australia’s northern coast from the Rowley shelf, east to Darwin, past the Torres Straight, the Great Barrier Reef and south to Queensland. It effectively ranges across the Solanderian region and part of the Dampierian region. This is quite unusual, as many Australian endemics have sisters that occupy separate coasts. Chaetodontoplus meredithi and C. personifer, for example, are found on the Eastern and Western Coasts respectively, where they are divided by the Torres Strait. Because of its distribution, C. muelleri is strongly sympatric with C. marginalis. There are sightings of this species in Fak Fak, West Papua, but these are unsupported and not concrete.

Chelmon muelleri with clean, distinct banding. Note the convergence of the 2nd and 3rd bands. Also note the obfuscation of the dorsal fin ocellus, and the bump on the nape. Photo credit: Michael Moye.

C. muelleri is the least likely species to be encountered in the trade, although it does make its occasional rounds in wholesalers. It’s biology and captive requirements are identical to the preceding Chelmon species. Hailing from Australia, it is sturdier and fares better in captivity.

Chelmonops

Chelmonops curiosus in Rapid Bay, South Australia. Note the turbid, silty reef habitat. Also note the prominent dorsal fin extension. Photo credit: Fishes of Australia.

The generic epithet “Chelmonops” translates to “Chelmon-like”, and indeed, Chelmonops bears a striking resemblance to its tropical sister genus. Colloquially known as Talmas, the two species are entirely and strictly subtropical, found below the Tropic of Capricorn on the southeastern and western coasts of Australia. They differ from Chelmon in possessing two extra dorsal spines (11 vs. 9). Aside from that, the two genera share similarities in their biology and habitat preference.

Chelmonops curiosus – The Western Talma

Chelmonops curiosus. Note the strongly falcate posterior dorsal fin elongation. Photo credit: Rudie Kuiter.

C. curiosus is the first of two cold-water butterflyfishes found in the Australian subtropics. In C. curiosus, the ground coloration is steely gunmetal with varying amounts of dark shading. The body is decorated in four vertical black bands, each increasing slightly in width towards the posterior. The edges of these bands are margined in silver. The pelvic fins are black. The posterior soft dorsal fin is greatly extrapolated into a falcate extension, where it may be hooked at the tip. This morphology serves to differentiate it from the following species. In juveniles, the soft dorsal fin is truncate, and marked with a prominent ocellus, but this eventually fades into an inconspicuous smudge with age.

C. curiosus is distributed from Geraldton, Western Australia, tracing the southern coastline to Port Lincoln. This species is endemic to the Flindersian quadrant, and on the opposite coast, is replaced by its sister species, C. truncatus. It frequents turbid coastal reefs in shallow water, often near pylons and jetties. Juveniles are very often found swimming in macroalgae groves.

Because of its subtropical nature, C. curiosus fares poorly in captivity, and must require cold water to thrive. Aside from that, its requirements are fairly similar to Chelmon. The species is only occasionally available in the trade from Western Australian imports.

A juvenile swimming in macroalgae. Note the short dorsal fin extension in this young individual. Photo credit: Fishes of Australia.

Chelmonops truncatus – The Eastern Talma

Chelmonops truncatus in the usual sandy, macroalgae-laden habitat. Photo credit: Fishes of Australia.

Chelmonops truncatus is almost identical to the previous species, with the exception of a few minor modifications. As its name suggests, the dorsal fin is significantly more truncated, with the filament severely reduced in comparison. The fins and bands are often slated in deep bordeaux, lending a dark, erythric appearance under certain light conditions. Juveniles are, as usual, in possession of a prominent dorsal fin occelus, but this disappears into a smudge with age. The smoothness of the posterior dorsal fin is markedly noticeable in the young stages, and only elongates slightly in adults. This differences in posterior dorsal fin morphology, as well as their allopatric distributions, are the most reliable diagnostics between the two species.

Adult C. truncatus. Note the prominent erythric slating over the fins and bands. Also note the short dorsal fin extension. Photo credit: Tom Davis.

C. truncatus is restricted to the southeastern coast Australia, from the Gold Coast to Canberra. It is the Peronian counterpart to C. curiosus on the western and southern coast. Like C. curiosus, it can be found in the same habitats of turbid coastal reefs replete with macroalgae. The species is rare in the trade, and is almost never exported. It shares the identical captive requirements as the preceding species, especially with regards to the provision of cold water.

Chelmon and Chelmonops both offer an interesting perspective into the world of butterflyfish far removed from the stereotypical reef setting. These beaked members are fond of murky, otherwise repulsive conditions by recreational standards, where they thrive on worms and other benthic invertebrates. In examination of their biogeography, we see a fairly expected trend following the various endemic regions of Australia. With the exception of C. muelleri, C. marginalis and C. rostratus occur almost exclusively on opposite sides of the Torres Straits; although the former strays very weakly across, while the latter continues extensively northwards into the Indo-West Pacific. C. curiosus and C. truncatus likewise are confined to their respective coastal quadrants, specifically, the cold, subtropical lower half of continental Australia.

These fishes, although challenging in captivity, live in some of the more peculiar and challenging terrains on the reef. Although perfectly happy in a standard reef tank, they will have no qualms making themselves at home in your refugium or coastal, turbid reef biotope (should you decide to make one). This sums up the first of three related articles. In the next installation, we delve into the genus Forcipiger, where the members there exhibit some of the most aggressive biogeography of any known Chaetodontid.

A special thanks goes out to Dr. Anthony Gill, for his engaging repartee and shared likeness for the genus Chelmon.

Me fascinan los peces