By James W. Fatherree

Of all the various kinds of macroalgae that can be added to a marine aquarium, the most common are the species belonging to the genus Caulerpa. Many of these species are attractive and fast growing, are inexpensive, and can even be useful in some ways. Thus, it’s easy to understand why these are so popular. However, despite all this, few hobbyists understand just how different they are from the “regular” plants that we see in our everyday lives. With that in mind, I’ll give you the basics of caulerpid biology, go over some of their potential uses, and then point out some of the potential problems they can pose, too.

To start things off, different types of marine algae can be split up into three basic groups. There are the brown algae which belong to the group Phaeophyta, the red algae which belong to the group Rhodophyta, and the green algae which belong to the group Chlorophyta. These different types of algae are obviously placed into these groups according to their colors, and each of these groups has members of varying complexity that can be further divided into microalgae (the tiny, dust-like varieties) or macroalgae (the larger, more complicated varieties).

Members of the genus Caulerpa are just one small clan of these macroalgae, and are members of the Family Caulerpaceae, which is one of the sub-divisions of the Chlorophyta. And, at least in the aquarium hobby, the genus name is also used as their common name. Due to this fact, when writing about them the general tendency is to use normal print when using caulerpa as a common name and to italicize it only when a particular species is being discussed. I’ll be doing the same, and will use “caulerpa” to mean all the species as a whole.

Caulerpa’s overall structure is exceptionally simple relative to that of “regular” plants, which are better called vascular plants. Essentially a specimen of caulerpa is just a uniquely-shaped fluid-filled tube called a thallus, which lacks all the sorts of tiny tubes and plumbing that we see running inside vascular plants.

This thallus is typically covered by numerous short structures called stipes, which are similar to a vascular plant’s stems. These stipes in turn give rise to structures called blades, which are usually (but not always) similar in appearance to the leaves of a vascular plant, too. There are also numerous root-like structures called rhizoids on the undersides of the thallus, which act as holdfasts to keep the algae attached to whatever it is growing on. So, all in all, caulerpa doesn’t look particularly different than any vascular plant on the outside, even though it is dramatically different on the inside. Of course there’s a reason that caulerpa appears so similar to a vascular plant, as both are trying to do the same thing. Both need to gather sunlight for photosynthesis, so they obviously need leaves or blades, while roots and rhizoids can hold both in place.

Caulerpa can be found in a variety of environments in tropical and subtropical areas, and most often grows on sandy and muddy bottoms. It grows like a creeping vine, sending out thin runners that take root in/on the substrate and then produce new blades overhead. Single strands can run for several feet, and my guess is that they can keep growing until something eats the end. The blades themselves can be highly variable in size and shape depending on the species, but most are only a few inches in length. However, in some cases they can reach sizes in the neighborhood of 12 inches and can look pretty much just like beds of turtle grass (which is a vascular plant). The amazing thing is that when some species are growing at full speed each runner can easily grow close to an inch per day, which allows them to cover large areas of seafloor exceptionally quickly; especially when compared to the spreading rate of corals and many other reef critters.

In aquariums this can be wonderful, especially given the variety of forms the different species come in. Some are grass-like, some are grape-like, some are fern-like, etc. All look nice and can add to any aquarium that has sufficient lighting to keep them alive. Caulerpa, like other types of algae, can also help maintain good water quality, as it extracts a number of unwanted nutrients from the water and assimilates them into its tissues as it grows.

For example, algae suck up nitrogen-based compounds like ammonia. Thus, they act as biological filters, much like the bacteria found in trickle filters, undergravel filters, or coating grains of sand, gravel, and live rock in other systems. Algae also use phosphate as a nutrient, which is the number one fertilizer for unwanted algal growth (like hair algae and microalgae growing all over the glass, etc.). So, if you have plenty of caulerpa growing in a tank it will compete with other forms of algae you don’t want, and can greatly reduce or practically stop its growth, which means less cleaning for you. Phosphate is also detrimental to corals and other organisms that build calcium carbonate skeletons because it interferes with the precipitation process they use to make them. Thus, the removal of phosphate by algae is a good thing for more than one reason. All you have to do is remove some of the algae now and then, which will in effect be removing unwanted nitrogen and phosphate from the aquarium system.

This is why caulerpa and other types of macroalgae can also be good stuff for use in a refugium tank that’s being used as a filtration device. Many hobbyists grow various algae in secondary tanks of some sort and plumb them to their main tanks to do just this. And these refugia are then provided with their own light source and substrate for the algae, which will grow and help maintain water quality as it is pruned back occasionally, all while being out of sight.

However, if you’re thinking about using macroalgae as a large-scale means of filtration rather than as a decoration only, I suggest you do a considerable amount of homework on algal filtration before getting started. It works, but it isn’t foolproof or maintenance free. There are also other types of algae you can use, which may be more suitable depending on your particular set-up.

Anyway, caulerpa may sound too good to be true, but there are a few cases when it can be a problem instead of a solution. First of all, it does grow, and fast. The problem here is that it can easily overrun just about anything else in your aquarium if you let it, and can even kill some things if it overtakes them. As new rhizoids are produced, they can take quite a foothold on corals, clams, etc. and can even penetrate the soft tissues of some of these organisms. Likewise, caulerpa can easily grow thick enough to shade out and smother corals and such. So, you’ll have to keep it in check and make sure it doesn’t interfere with anything else that may end up in its way.

Be mindful of caulerpa that grows over corals. Not only can it smother them, its rhizoids can actually penetrate a coral’s tissues and damage it. Pictured are C. macrophysa and C. racemosa.

Caulerpa also exudes a number of chemicals that deter herbivorous fishes, but these have been reported to bother some corals, too. While it isn’t a problem at all in many aquariums, I have heard from various sources that mixing a lot of caulerpa with a lot of small-polyped stony corals, like Acropora and such, can lead to problems for the corals. Still, in my own experience, this hasn’t been an issue. Fortunately, water changes, skimmers, and activated carbon can all help to keep these compounds from building up, thus it likely won’t take anything that you’re not already doing or using to keep them from becoming a problem.

There’s also the yellowing of aquarium water. Like other algae, caulerpa also produces yellowing organic compounds, which seep out into the environment and in time will give an aquarium a tinted look. If you want to see for yourself just try sticking a sheet of white paper to one end of your aquarium and then go look at it through the water from the other end. If you’re not using carbon and/or a good skimmer and/or not doing adequate water changes, chances are the paper isn’t going to look as white as you might expect. The more caulerpa you have, the faster the water will become yellowed, too. So, you’ll want to do what you can to prevent this. Again, using carbon, skimmers, and water changes to counter this buildup has always kept it from becoming a problem for me.

Lastly, if you keep caulerpa long enough you’re very likely to eventually experience a periodic “crash”. Caulerpa reproduces in two very different ways, one of which can be problematic. The first is via fragmentation, which means that pieces that get torn away from a clump/strand can grow into another clump/strand. In fact, if a single blade settles into the right spot it can grow into another full-size clump/strand in just a few days. As you can imagine, this works very well with waves and algae-eating predators breaking off parts, which constantly creates pieces that are left to be carried away and start new growth somewhere else. And, lucky for us, it can be broken up by collectors and shipped to stores, or by hobbyists to spread around an aquarium, or moved to another tank, too. All you have to do is figure out a way to hold a piece in place long enough for it to grow some new rhizoids and attach itself to the substrate. However, the other means of reproduction is called sporulation, and is a bit more complicated.

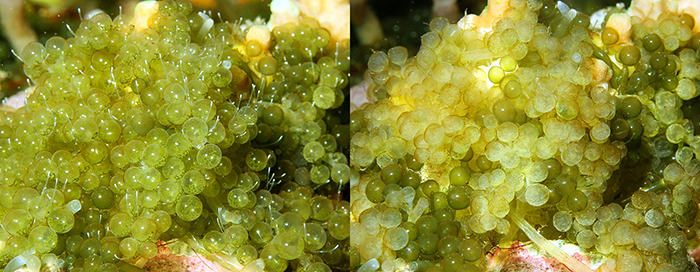

Here you can see a clump of C. microphysa that’s about to crash, and the same clump after most of it has done so. Nothing is left of much of it, except for an empty thallus that will rapidly turn to mush and decay if not removed quickly.

Vascular plants have specific organs that produce reproductive cells and structures, but caulerpa can produce reproductive cells throughout the thallus. These cells are generated within the liquid contents of the body, and when enough are formed it can essentially self-destruct and release all of them into the environment. The hollow fluid-filled body ruptures and the contents spill out into the surrounding waters leaving the empty, translucent body behind to quickly decay. This is often called “going sexual” by hobbyists, and has the potential to rapidly degrade water quality if it’s not dealt with.

The problem is that when this occurs it often happens on a large scale, which can be trouble in an aquarium. It’s rather unpredictable too, although there are signs of an impending crash just before it happens that I’ll get to momentarily. The immediate effect of a crash is a clouding of the tank, sometimes turning the water quite green depending on the size of the tank and the amount of caulerpa that goes sexual. And, because the deceased remains of the body are left behind, you can end up with a mess of dead algal goop, as well. On top of that, the cells and fluids that escape and create the green discoloration will also die off in an aquarium and further reduce water quality.

With all this in mind, it’s obviously important to remember to take action as soon as possible if this happens in your aquarium. Manually remove as much of the dead material as you can as quickly as possible and use a powerfilter to help clear the water if it’s green enough to worry about. I say green enough because you may have a single strand crash, which may be negligible in most tanks, or conversely you may have several big clumps/strands crash simultaneously, demanding attention. If you do use a powerfilter, make sure to clean the filter’s media as soon as the water clears too, so that the green stuff doesn’t just die in the filter and foul the water anyway. Luckily, as bad as this might sound, I haven’t had anything else in a tank die due to a sporulation event, so don’t panic!

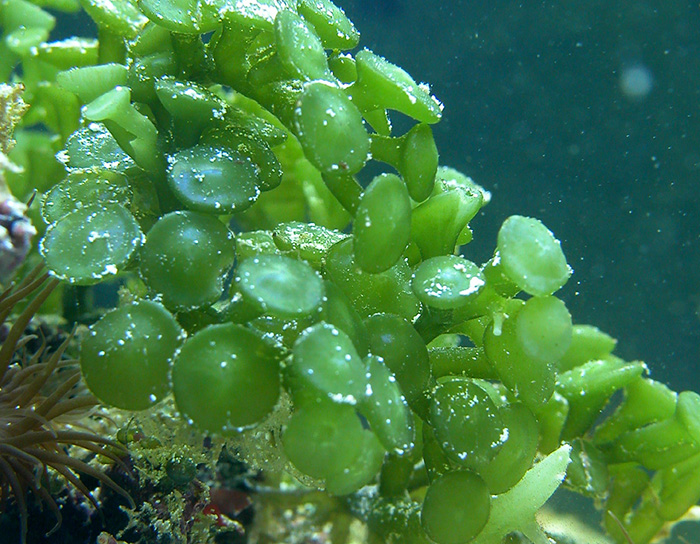

This is C. racemosa, but regardless of the species, caulerpa will get this splotchy look and will produce numerous little hairs/fingers on the thallus just before it crashes.

The best thing to do is to try to avoid sporulation in the first place and/or learn to spot it before it happens and take preventative action. While it is by no means 100% effective, keeping the stuff pruned back is really the most effective way to go about it. Just reach in and pull out pieces here and there in order to keep it from growing unchecked because it seems that when it gets crowded it crashes. Also, because it typically crashes one strand or a clump at a time, it’s better to keep several smaller patches spaced around a tank or in a refugium rather than one big one. That way you’ll more than likely see a little crash now and then instead of a big one. As far as catching it early goes, the signs to look for are a splotchiness on the thallus/blades and a number of tiny hair or finger-like projections that develop on them. If these little things show up, start pulling the affected stuff out!

Also note that when I keep lots of caulerpa in a tank or in a refugium, I try to mix up two or more different species if possible. Each can behave differently when it comes to crashing, so having more than one kind will help ensure that you won’t have all of your caulerpa go at the same time. Some suggest that leaving the lights on over a refugium 24 hours a day will keep the caulerpa in it from crashing as often, too. But, I’ve also heard that even that won’t work all the time. So just remember, no matter what you do, it’s almost certain to happen on some scale at some point anyway, but can be dealt with.

To wrap things up, I have to give a warning to readers in California, Oregon, Alabama, Massachusetts, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Vermont, as these states have banned the possession and/or trade of one or more species of caulerpa (1). As it turns out, somehow some cold-water tolerant Caulerpa taxifolia was introduced to California waters in the San Diego area and essentially took over in places. It covered vast tracts of seafloor in some areas and has wreaked havoc on the local ecosystems, which were not ready for such an assault.

Unfortunately, it had to be dealt with harshly, and was subsequently banned in California, with the other states above following along. As I’ve read on a number of websites, initially policy makers seemed to get in too big of a hurry and were trying to ban all species of caulerpa. But, apparently this cold-water tolerant species is actually much hardier than most all of the other species, which won’t tolerate the cooler water temperatures off California. So, banning all species didn’t make much sense after all.

Unfortunately, it had to be dealt with harshly, and was subsequently banned in California, with the other states above following along. As I’ve read on a number of websites, initially policy makers seemed to get in too big of a hurry and were trying to ban all species of caulerpa. But, apparently this cold-water tolerant species is actually much hardier than most all of the other species, which won’t tolerate the cooler water temperatures off California. So, banning all species didn’t make much sense after all.

Instead of a total ban, the State passed legislation intended to keep out the C. taxifolia, and all of the species that could be mistaken for it based on appearance – and a couple of others, too. From the California Code 2:

(a) No person shall sell, possess, import, transport, transfer, release alive in the state, or give away without consideration the salt water algae of the Caulerpaspecies: taxifolia, cupressoides, mexicana, sertulariodes, floridana, ashmeadii,racemosa, verticillata, and scapelliformis. (Note: the other states above have banned only C. taxifolia).

(b) Notwithstanding subdivision (a), a person may possess, for bona fide scientific research, as determined by the department, upon authorization by the department, the salt water algae of the Caulerpa species: taxifolia, cupressoides, mexicana,sertulariodes, floridana, ashmeadii, racemosa, verticillata, and scapelliformis.

(c) In addition to any other penalty provided by law, any person who violates this section is subject to a civil penalty of not less than five hundred dollars ($500) and not more than ten thousand dollars ($10,000) for each violation.

Thus, you’d better be careful or the man may be knocking on your door to check on your caulerpa, as a few of these are some of the most popular of the dozens of species out there. If there’s anything else for me to say about it, I guess I should make the point that it is bad to release anything at all from an aquarium into the wild (even though there’s no real evidence that I’ve seen that the California problem was started by aquarists). So make sure you don’t do it, whether it’s a fish, a coral, a plant, or anything else. You never know what might happen.

References

(1) Southern California Caulerpa Action Team. URL: http://www.sccat.net/#federal-state-…al-laws-1e86c6

(2) Official California Legislative Information. URL: http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/calaw.html

0 Comments