Chaetodon sp. from Maria Atoll, 77 meters. Photo by Anthony Berberian.

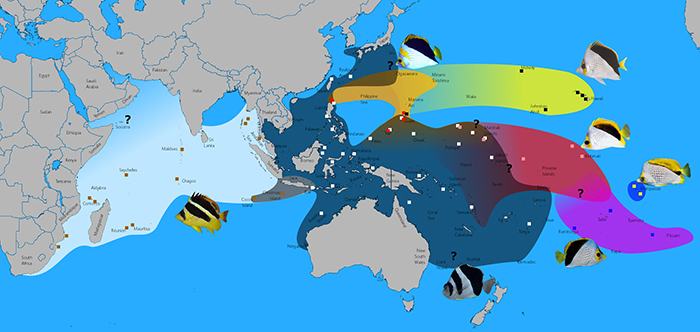

The butterflyfishes in the subgenus Roaops comprise a small and distinctive group of mesophotic species, hugely popular among aquarists thanks to their colorful patterns and general hardiness in captivity. They occur widely across the Indo-Pacific, from Africa to Hawaii, forming a single allopatric species complex. This is a pattern of speciation common to many widely distributed groups of reef fishes, but it was noted in a previous review that there seemed to be a peculiar absence in French Polynesia. As it turns out, this is not the case. A population of Roaops has actually been known here for decades, and new images of this rarely encountered fish are revealing that it, in all likelihood, represents an undescribed species.

Roaps distribution.

The first documented specimen, discovered by famed mesophotic ichthyologist Dr. Richard Pyle and collector Chip Boyle (of Peppermint Angelfish fame), was found in the late 1980s in Rarotonga at a depth of 100 meters. It was next spotted about a decade later when Livia and Yves Lefèvre encountered several individuals from the deep reefs (~70 meters) of the Tiputa Pass in Rangiroa. Diver Anthony Berberian observed another specimen to the south at Maria Atoll in the Gambier Archipelago. No doubt, others have seen this fish since, but, in total, there are just a handful of confirmed sightings.

Chaetodon from Vanuatu. A possible hybrid of the South Pacific population and C. burgessi? Photo by Richard Pyle.

It’s likely that this is relatively common butterflyfish across the South Pacific, but it seems that few divers ever venture here to find it. If we take the Polynesian distribution of the Black Tang (Zebrasoma rostratum) as an example, the full range could include Pitcairn, the Northern Cook Islands, Millennium Atoll, Tokelau and perhaps areas further west (e.g. Tuvalu, Wallis & Futuna). Brian Greene reports specimens encountered in Vanuatu that possessed an apparent hybrid phenotype, suggesting that this southern population might be quite widespread. Roaops do seem to be very capable of traversing the Pacific, as evidenced by records of the Hawaiian C. tinkeri in the Mariana Islands.

Chaetodon tinkeri , from Johnston Atoll. Note the thin, orange submarginal band in the dorsal fin and the yellow streak in the anal fin. Photo by Luiz Rocha.

In its appearance, this fish is remarkably similar to the Hawaiian C. tinkeri . Both have a dark posterodorsal coloration—quite different from the yellow of the C. declivis sandwiched between these two populations—but it’s the finer details which allow us to tell them apart. In the Hawaiian Tinker’s, the black patterning is consistent throughout and gives way to an orange submarginal band along the dorsal fin. In the South Pacific population, the black is more variable in its coverage, appearing more suffused and declivis-like in some specimens and with an irregular edge posteriorly, never showing the sharply delineated colors and orange submarginal band found in the true C. tinkeri.

Chaetodon sp. From Rangiroa, 75 meters. Photo by Yves Lefèvre.

The eye stripe also differs in a subtle, but noticeable, manner. In the Hawaiian C. tinkeri, the rear edge of this stripe is usually in line with the posterior margin of the eye, while those from the South Pacific have this line positioned further back, resulting in an isthmus of yellow connecting the upper and lower portions of the stripe. And, in general, those from Hawaii tend to have more black along the margins of this stripe—occasional specimens even have black smudging the interior of this stripe—while those in the southern population tend to have little, if any, black present.

Another useful trait is the patterning found on the anal fin. In most Hawaiian specimens, there is a short, yellow submarginal streak that overlaps the interface where the black marking along the back meets the white base coloration. This is absent in all known South Pacific specimens. Taken together, these seemingly minor differences allow us to readily diagnose these separate populations, and, given the vast distance separating them and their positions in known hotspots for endemic speciation, it seems reasonable to presume that these southerly specimens are an undescribed species, one which is likely to prove more closely related to the neighboring C. declivis than to the superficially similar C. tinkeri.

Chaetodon sp. From Rarotonga. Photographed in an aquarium. Photo by Richard Pyle.

With there being so many recognizable differences with this fish, you might be wondering why it has not been named yet. When Dr. Pyle discovered it nearly thirty years ago, he collected specimens and even kept it briefly in captivity (likely the only time this fish has ever been seen in an aquarium). The challenge in scientifically describing this population has more to do with the extensive hybridization of Roaops that appears to take place in Micronesia. At this point, it might be safest to say that there is no true species present in that region, just a genetic soup of chimeric individuals which can possess almost any combination of features. Specimens in the aquarium trade have been referred to as the “Tarawa Tinkeri Butterflyfish”, after the source of many of these individuals, Tarawa, Kiribati.

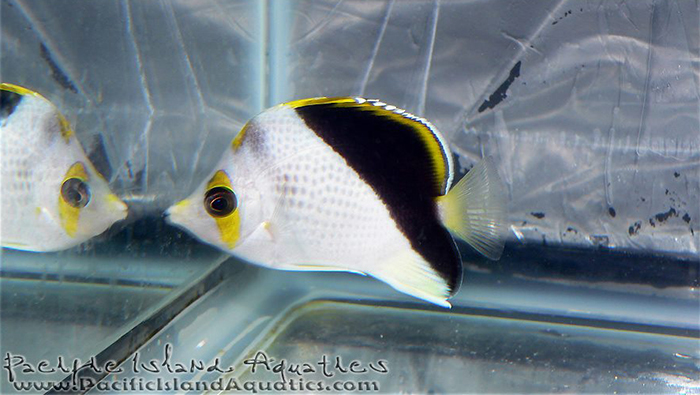

Marshall Islands hybrid, most plausibly a C. declivis X C. burgessi. Photo by Pacific Island Aquatics.

But it’s unclear if the true Tinker’s Butterflyfish has anything to do with any of these muddied hybrid forms. A purported specimen of C. tinkeri collected from Enewetak in the Marshall Islands has been offered as proof that this Hawaiian endemic occurs in Micronesia, but Dr. Pyle reports that even this individual was intermediate in appearance, resembling our undescribed South Pacific Roaops more than the true Hawaiian species. Similar specimens from the aquarium trade show evidence of the nuchal band diagnostic for C. burgessi and C. flavocoronatus, mixed with a declivis-like yellow in the submarginal band of the dorsal fin.

There’s even been a sighting of what appears to be a full-blooded C. declivis in the Marshall Islands, but, without genetic analysis, it seems presumptuous to identify any fish from that region at a species level. Owing to all this uncertainty, our understanding of this group’s species-level biodiversity is likely to remain frustratingly incomplete into the foreseeable future. How do we define the Pacific Roaops when these fishes so blatantly laugh in the face of species boundaries? Surely the population in the South Pacific is different from those found elsewhere, but, if it blends seamlessly into the neighboring hybrid forms in Micronesia, can we truly treat it as a separate species?

0 Comments