I suppose most serious hobbyists will watch a program concerning corals reefs on the Discovery Channel or Animal Planet (or other) television channels. With the cost of big-screen televisions rapidly falling in price and their use becoming commonplace, viewing these video essays on a giant screen can be spectacular. If you’re a coral afficianado such as me, you’ll especially enjoy those shows dealing with the invertebrates of coral reefs. Some of the most astounding videos can be of coral spawning. We the extreme close-up video of corals extruding their egg bundles to the shallow seas during early evening. It would be easy to believe that all corals reproduce in this manner but such is not the case. One such case is the coral Porites lutea in Hawaii.

Figure 1. A field of purple Mound Corals (Porites lutea) in Kahalu’u Bay, Hawai’i. Note the tiny black ‘Humbug’ damselfish (Dascyllus sp.) bravely defending its home, the Pocillopora meandrina at the bottom center of the photo (by the author).

Facts about Porites lutea (Milne-Edwards and Haime, 1860):

Phylum: Cnidaria

Class: Anthozoa

Subclass: Hexacorallia

Order: Scleractinia

Suborder: Fungiina

Family: Poritidae

Genus: Porites

Species: lutea

Porites lutea (formerly P. evermanni) is a common coral in Hawai’i and throughout the Indo-Pacific Ocean. These animals are mostly often found in water up to 6 meters (20 feet) in depth. Coloration can be brown, yellow-brown, gray, sometimes with purple highlights and less often entirely purple. It is never yellow-green like P. lobata (Fenner, 2005). Porites colonies are among the longest living animals known where some are hundreds of years of age.

Kahalu’u Beach Park on the west coast of the Big Island of Hawai’i provides a perfect spot to easily observe P. lutea and other coral colonies. A mysterious rock wall (Hawaiian legend suggests the wall was built by the Menehunes – a race of secretive, tiny people) shelters the bay from intense wave action and provides calmer waters preferred by P. lutea and a rapidly aging coral observer (me). Hence Kahalu’u is also a favorite spot to document coral spawning activities. Members of the ReefWatchers group have observed spawnings of Pocillopora meandrina, P. eydouxi, and Leptoseris bewickensis there.

The Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) Division of Aquatic Resources monitoring team members provided some details of P. lutea’s reproductive behavior (Sara Peck, personal communication). Evidence of a spawning was observed on July 9th, 2009, sometime between noon and 1400 hours, while DLNR’s Dr. Bill Walsh and Brent Camen were monitoring a transect line off the west coast of the Big Island Of Hawai’i. They observed a large cinnamon colored cloud of spawn surrounding and obscuring a P. lutea colony estimated to be some 9 meters (30 feet) across.

Would these corals spawn again the next day? Intrigued, I cancelled the plans I had and prepared to photographically document the daytime spawning of this species.

I had hoped to be in the water at noon on July 10th, but as luck would have it, I would not get wet until about 1230 hours. The day was one straight out of a travel brochure – a blue sky above the palm trees, plenty of sun, and calm warm water. Snorkeling across the reef flat to the coral bommies, I noticed the water seemed a bit turbid, and within five minutes of entering the water I would know why. There was a mass spawning event of P. lutea occurring. The first colony (out of 7) I observed was apparently finishing its spawning, as I saw only one slow discharge of sperm. I hurriedly and clumsily opened my dive bag to remove a kitchen baster and a small plastic bottle and collected a spawn sample. I began to look for further evidence of spawning, and didn’t have to go far – I entered a shallow depression filled with P. lutea – and they were all spawning (this almost mono-specific stand of Porites is in the introductory photo which was taken after the spawning event was over). Things were getting hectic. I had the baster and bottle in one hand, and the underwater camera in the other. Get a photo – take a sample. I needed some help. I surfaced and hailed a nearby snorkeler. I rapidly told him of the situation, and asked if he would help me. He nodded his head, and I began to take more photos and samples. I never saw that snorkeler again and can only suppose that swimming in a sea full of coral gametes held absolutely no appeal to him.

The best show was still to come. Even through the water’s reduced visibility (estimated to have dropped to only 6 meters, or ~20 feet from a normal 16 meters – ~50 feet), I could see the outline of a massive P. lutea surrounded by an underwater fog of gametes (see Figure 2). I watched in awe as this coral slowly released gametes for at least 20 minutes (some colonies were observed spawning for as much as 30 minutes). More photos and samples were taken. After an hour, the spawnings stopped, but I stayed in the water for another 30 minutes in hopes of seeing female colonies releasing eggs (quick looks at my bottle with composited spawning samples had revealed no eggs during this very hectic hour). I reluctantly left the water as the bay’s normal clarity returned, suggesting the event was over.

Once in the lab, I made my notes and a microscopic exam of the spawn sample. Unfortunately, I could not spot any eggs either visually or microscopically, and after examining quite a few detritus particles, I abandoned my search.

Figure 2. Spawning of a male P. lutea. Note the corona of cloudiness to the right and above the colony – these are release of sperm. Photo by the author.

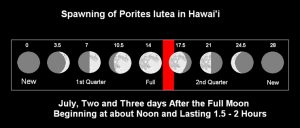

Combining two observations, this is what we know about daytime spawnings of Porites lutea.

Spawning Event of July 9, 2009 (Observers: Walsh and DLNR monitoring team)

- Though not directly observed, a large female colony at a depth of 10 meters (30 feet) was obscured by a cloud of gametes (eggs).

- The cloud of eggs was cinnamon in color*, and ‘sticky’, clinging to wetsuits.

- Spawning occurred between noon and 1400 hours.

* Interestingly, at least some P. lutea eggs are known to contain zooxanthellae when released during spawning (symbionts are obtained from the parent colony through a process known as vertical transmission). This might account for the reported brownish coloration. However, see comments on the possibility of P. lutea being a gonochoric brooder below.

Spawning Event of July 10, 2009 (Observer: Riddle)

- Spawnings of 7 colonies were observed

- Colonies were apparently all males

- Slow continuous release of sperm appearing as ‘white smoke’ and lasting up to 30 minutes

- Entire spawning lasted at least one hour (12:35 – 13:35 hours)

- These spawnings occurred 2 and 3 days after full moon and on a rising tide (approximately 2.25 and 1.5 hours after the morning low tide, 7/9/09 and 7/10/09, respectively).

- Sexuality: Gonochoric (separate male and female colonies)

- Reproductive Mode: Broadcast spawner (sperm)*; no egg release observed

- Sexual Maturity Size: Smallest spawning colony was 450 cm2 (roughly 72 square inches – 6×12 inches), but maturity could quite possibly be even smaller.

- No eggs were collected; however previous reports state eggs contain zooxanthellae (Neves, 1998).

* Parthenogenesis and brooding have also been reported as a possible reproductive mode in P. lutea (Fadallah, 1983).

Our observations are at odds with that reported by Kenyon (1995). Histological examinations of 3 P. lutea specimens gathered in May in Palau (7N, 138E) found no eggs.

Does P. lutea spawn earlier (or later) than those in Hawai’i, or is this a case of mistaken identity? Which leads us to our next topic.

Taxonomy

Corals are generally difficult to identify to the species level, and the specimens of genus Porites are particularly so. Porites lutea in Hawai’i were formerly called P. evermanni (thought to be endemic to Hawai’i). However, Forsman et al. (2009) report samples of Hawaiian P. evermanni are genetically indistinguishable and similar in corallite characteristics from a Panamanian Porites. In addition, it was identical genetically to a branching morph of P. annae from American Samoa.

Plasticity of coral skeletons due to any number of pressures creates the ‘coral species problem’ that will likely take some time to resolve.

We used the identification of P. lutea suggested by Fenner (2005), where gross morphology of the skeleton is used, as well as color. His observations and recommendations allowed us to successfully locate spawning Porites colonies within Kahalu’u Bay. A later conversation with Dr. Paul Jokiel validated Fenner’s identification methods.

We should note that the Porites species closely resembling P. lutea is P. lobata. Information available to us states that Hawaiian P. lobata spawns during July and August evenings, two to four nights after the full moon and at 2100-2300 hours, or 0100-0300 hours (Gulko, 1995).

In Closing

To our knowledge, this is the first report of P. lutea’s daytime spawning as early as July in Hawaiian waters. There is a report of Hawaiian P. evermanni reproducing in August and September just after the full moon (Hunter and Hodgson, unpublished, in Neves, 1998; also in Richmond and Hunter, 1990). Richmond and Hunter (1990) reported

P. lutea spawns during November and January (summer) on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Obviously, our initial report is preliminary and will be refined with time.

The take home message is clear – not all corals spawn at night or do our observations of P. lutea’s spawning behaviors correspond to any particular lunar phase. In fact, our observations suggest spawnings are random during periods of warmer water.

There is yet another possibility – some Porites lutea populations could use gonochoric brooding as a reproductive strategy, where sperm is released to the water column and fertilizes females’ internally held eggs. This is rare in corals (estimated to be used by 7% of coral species) but has been reported in Porites rus colonies in Zanzibar (Bronstein and Loya, 2011). Hence, Porites species have been reported to use many reproductive modes – parthenogenesis, gonochoric broadcast spawning and gonochoric brooding (in addition to fragmentation).

Footnote

No observations, mostly due to time constraints of volunteers) of P. lutea spawning were made in 2010 (although they surely occurred). Our hopes are high for the 2011 spawning season, and we hope to have new information to report later this year.

References

- Bronstein, O. and Y. Loya, 2011. Daytime spawning of Porites rus on the coral reefs of Chumbe island in Zanzibar, Western Indian Ocean (WIO). Coral Reefs, in press.

- Fadallah, Y., 1983. Sexual reproduction, development and larval biology in Scleractinian corals: A review. Coral Reefs, 2: 129-150.

- Fenner, D., 2005. Corals of Hawai’i. A Field Guide to the Hard, Black, and Soft Corals of Hawai’i and the Northwest Hawaiian Islands, Including Midway. Mutual Publishing, Honolulu. 144 pp.

- Gulko, D., 1995. Hawaiian Coral Reef Ecology. Mutual Publishing, Honolulu. 245 pp.

- Forsman, Z., D. Barshis, C. Hunter and R. Toonen, 2009. Shape-shifting corals: Molecular markers show morphology is evolutionarily plastic in Porites. BMC Evol. Biol., 9:45.

- Kenyon, J., 1995. Latitudinal differences between Palau and Yap in coral reproductive synchrony. Pac. Sci., 49(2): 156-164.

- Neves, E., 1998. Reproduction in reef corals. Results of the 1997 Edwin W. Pauley summer program in marine biology. University of Hawai’i, Hawai’i Institue of Marine Biology. Technical Report No. 42.

- Richmond, R. and C. Hunter, 1990. Reproduction and recruitment of corals: Comparisons among the Caribbean, the tropical Pacific, and the Red Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 60: 185-203.

- Thongtham, N., Transplantation of Porites lutea to rehabilitate degraded coral reef at Maiton Island, Phuket, Thailand. Proc. 11th Int. Coral Reef Symposium.

- Veron, J.E.N., 2000. Corals of the World. Australian Institute of Marine Science.

Dana, thank you for writing this wonderful article, we run the Coral Conservancy and we are trying to figure out a way for a temporary swimming closure at the Makai Pier on Oahu during the spawning periods of Porites Lutea/Evermanni due to lack of water flow, high coral density, and deadly cosmetics to gametes. Please reach out to me to talk more about this. Thank you.