There probably are few aquarium fish that are as beautiful, interesting and distinctive as the freshwater stingrays. They are typically the center of attention in any public or private exhibitry that they are displayed in. Certain special considerations, however, must be made to properly house them, which preclude many types of aquarium systems, aquascapes and tankmates outright. Still, while they require a high level of rather specialized husbandry, the rewards for successfully maintaining these remarkable animals are great.

During the rainy season, the Orinoco River can expand to a width of 14 miles (22 kilometers). Photo by Pedro Gutiérrez.

Several genera of freshwater stingrays appear in the ornamental fish trade. However, those of the genus Potamotrygon, the so-called river stingrays, are undoubtedly the most common. Reasons for this are many. They are strikingly handsome fishes. They reach relatively modest adult sizes. They generally accept a variety of readily available aquarium fish foods. Under the care of an experienced aquarist, long-term survivability is quite feasible. Most notably, they even can be bred and reared in captivity.

This piece discusses the classification, distribution, ecology and conservation of river stingrays; a following piece will discuss river stingray morphology, reproduction and husbandry.

Classification

The true rays and skates, Superorder Batoidea, are assigned (along with all other jawed cartilaginous fishes) to Class Chondrichthyes. They share Subclass Elasmobranchii with sharks and chimaeras. Rays account for about half of all elasmobranch species. Of the 500 or more described ray species, there are over 150 stingray species that are assigned to approximately 20 genera. Freshwater stingrays of the family Potamotrygonidae are assigned to the genera Paratrygon, Plesiotrygon, Heliotrygon and Potamotrygon. To date, as many as 20 described species are assigned to Potamotrygon. P. hystrix is recognized as the type species. Some aquarists use a P-number system (which is similar to the L-number system associated with loricariid catfishes) to classify these animals.

Below is a complete list of the currently valid names of species included in Genus Potamotrygon.

- Potamotrygon boesemani Rosa, M. R. de Carvalho & Almeida Wanderley, 2008 (Emperor ray)

- Potamotrygon brachyura (Günther, 1880) (Short-tailed river stingray)

- Potamotrygon constellata (Vaillant, 1880) (Thorny river stingray)

- Potamotrygon falkneri Castex & Maciel, 1963 (Largespot river stingray)

- Potamotrygon henlei (Castelnau, 1855) (Bigtooth river stingray)

- Potamotrygon humerosa Garman, 1913

- Potamotrygon hystrix (J. P. Müller & Henle, 1834) (Porcupine river stingray)

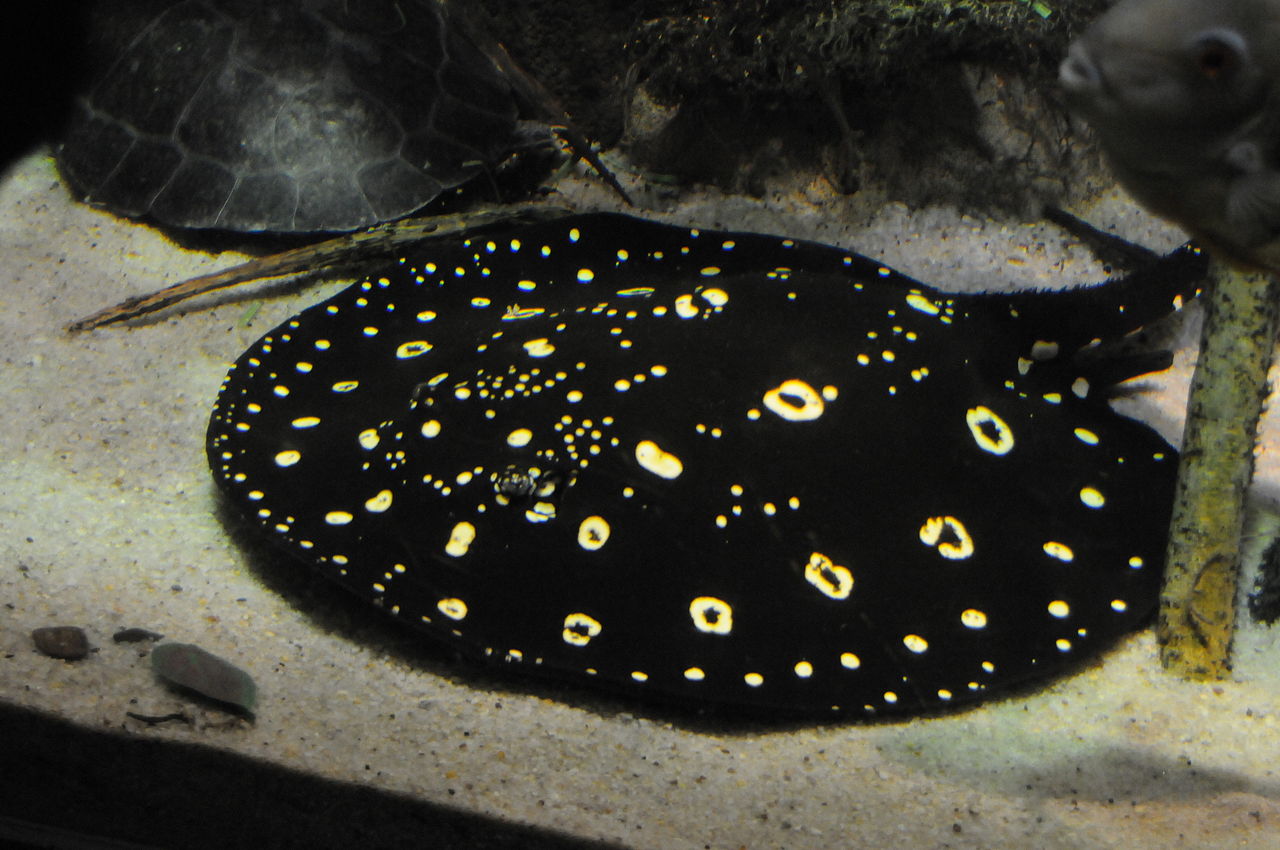

- Potamotrygon leopoldi Castex & Castello, 1970 (White-blotched river stingray)

- Potamotrygon magdalenae (A. H. A. Duméril, 1865) (Magdalena river stingray)

- Potamotrygon marinae Deynat, 2006

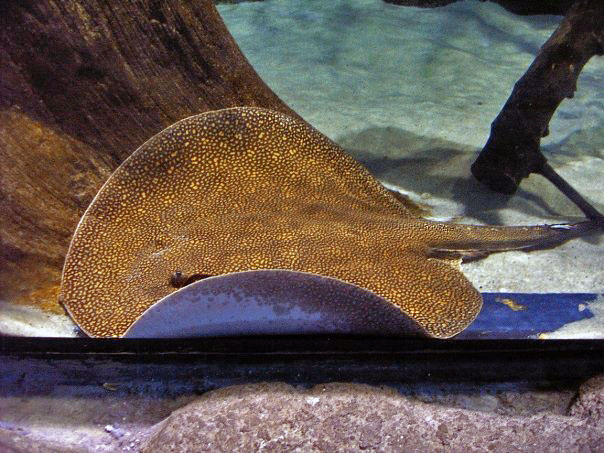

- Potamotrygon motoro (J. P. Müller & Henle, 1841) (Ocellate river stingray)

- Potamotrygon ocellata (Engelhardt, 1912) (Red-blotched river stingray)

- Potamotrygon orbignyi (Castelnau, 1855) (Smooth back river stingray)

- Potamotrygon schroederi Fernández-Yépez, 1958 (Rosette river stingray)

- Potamotrygon schuhmacheri Castex, 1964

- Potamotrygon scobina Garman, 1913 (Raspy river stingray)

- Potamotrygon signata Garman, 1913 (Parnaiba river stingray)

- Potamotrygon tatianae J. P. C. B. da Silva & M. R. de Carvalho, 2011

- Potamotrygon tigrina M. R. de Carvalho, Sabaj Pérez & Lovejoy, 2011 (Tiger ray)

- Potamotrygon yepezi Castex & Castello, 1970 (Maracaibo river stingray)

Genetic analysis of wild specimens suggests that the origin of the group can be attributed to a single colonization event. The role of hybridization in the speciation of the group, however, remains unclear. There is a considerable number of shared characteristics between species, as well as considerable variation within some species. The presently undescribed Itaituba river stingray (or P14), which evidently differs from P. henlei and P. leopoldi only in the size/number of spots, could possibly be one such variant or hybrid form. Indeed, some recent studies put into question the validity of the present taxonomic organization of these animals altogether.

Like other members of the genus, P. castexi can be found locked in ponds formed by receding floodwaters. Photo by Franklin Samir Dattein.

In the wild, P. henleifavors muddy bottoms where it preys heavily on gastropods. Photo by Christine Schmidt.

Distribution/ecology

Of the many, diverse elasmobranchs, Potamotrygonidae is the sole extent family that is completely restricted to freshwater. While potamotrygonids are primarily river dwelling (or potamodromous), they are capable of exploiting a variety of freshwater habitats. Potamotrygon is native to the murky river systems of neotropical South America. This highly specialized, monophyletic group occurs mainly within a narrow geographical range spanning the Amazon River Basin. Curiously, members of this genus are found only in those rivers that drain into the Caribbean Sea or Atlantic Ocean. However, they are not found in the upper Paraná basin, the northeastern Brazilian São Francisco basin, Argentinean rivers south of the La Plata River, or northeastern and southeastern Brazilian rainforest rivers that drain into the Atlantic Ocean. Potamotrygon usually inhabits ranges that are restricted to a single river system or basin. Usually, no more than a few species (P. motoro and P. orbignyi, for example) occur in the same basin. In certain cases, a species (P. leopoldi, for example) may be restricted to a single river.

The distribution of P. orbignyi within Amazonian estuaries is influenced by seasonal fluctuations of salinity. Photo by Claire Powers.

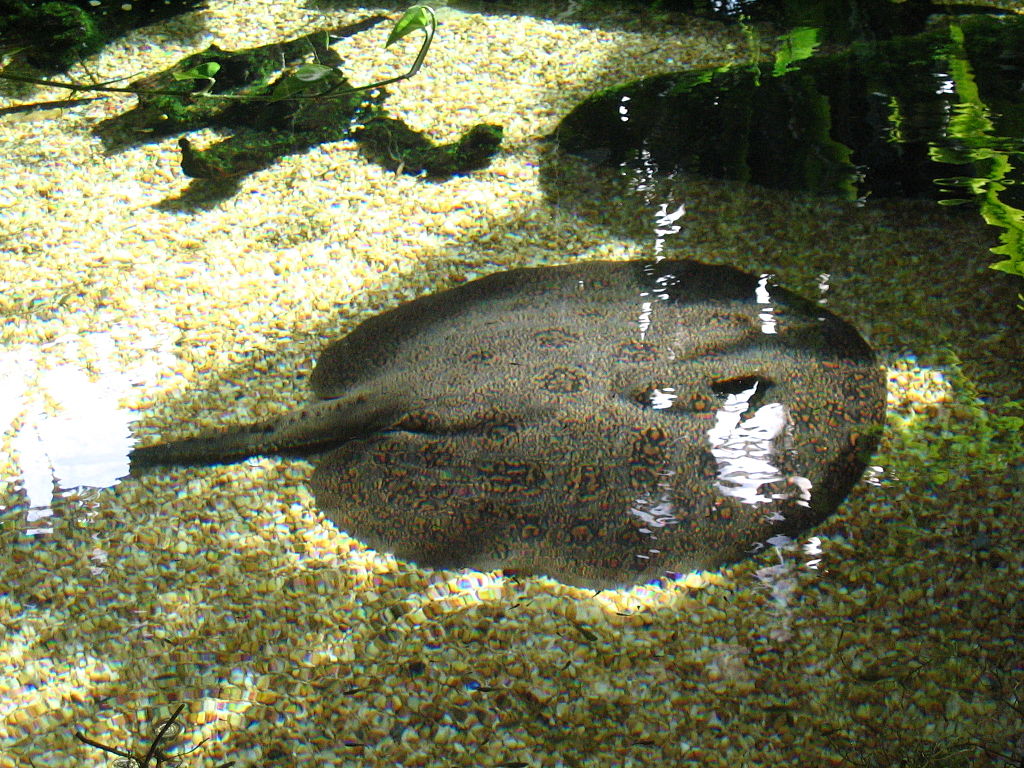

River stingrays dwell in a diverse range of freshwater environments, such as sandy lake beaches, flooded forests, and small, muddy creeks. Some species thrive under unusual environmental conditions such as very low pH or low dissolved oxygen concentrations (hence, one interesting adaptation to freshwater environments: the ability to float on the surface when bottom waters are oxygen poor).

However, river stingrays are restricted to water where salt concentrations do not exceed 3.0 ppt. Interestingly, potamotrygonid blood chemistry differs appreciably from marine and euryhaline elasmobranchs. For instance, because the rectal gland excretes little or no salt, they are incapable of retaining urea.

River stingrays tend to be more active at night, particularly while feeding. They are best described as nonspecialized predators. Wherever they occur, they generally are at the top of the food web. Adults prey mainly on fish, worms and small crustaceans, whereas juveniles prey mainly on small crustaceans and aquatic insects.

Conservation

In the wild, P. leopoldifavors rocky river bottoms where it preys heavily on freshwater crabs. Photo by Michael-David Bradford.

As they typically inhabit relatively restricted ranges, potamotrygonid stingray populations are especially sensitive to harvest as well as environmental disturbances. Both indirect threats (e.g., habitat destruction due to development, mining, and damming) and direct threats (e.g., the indiscriminate killing of stingrays as pests, collection for the aquarium fish trade) have resulted in tight regulations for stingray “fisheries” as well as CITES II protection. To date, five river stingray species have been registered in the IUCN Red List as threatened.

While river stingrays are seldom fished for food, they are often taken as trawl net bycatch. They are also under significant pressure from ornamental fisheries. Owing to a high incidence of hybridization (both intentional and accidental) within captive populations–and a growing demand for “pure” lines–trade in wild-caught specimens has become quite lucrative. This has not escaped the attention of individuals who now harvest river stingrays heavily in unprotected areas just outside the borders or poach where harvest is prohibited. 20,000 specimens are legally exported from Brazil annually, with some unknown number of individuals (especially P. henlei and P. leopoldi) exported illegally. Strangely enough, another estimated 20,000 individuals are destroyed each year during “cleanups” along stretches of river beaches frequented by tourists; the waste involved in this practice should be obvious to anyone.

Commercial river stingray breeding facilities are currently operating in the United States, Germany and Southeast Asia. Fortunately, the use of PIT tagging in the trade is slowly regaining the confidence of consumers who are again relying on breeders, rather than collectors, to supply “pure stock.” In fact, as breeders continue to increase production, they could potentially flood the market with captive bred product and all but neutralize the export of river stingrays from their native lands altogether. At the very least, relieving pressure on wild populations in this way could help to ensure that the existing legal harvest quotas will not be reduced, thereby keeping supply lines for wild genetics open.

Sources

- Kuba, Michael J., Ruth A. Byrne and Gordon M. Burghardt. (2010). A new method for studying problem solving and tool use in stingrays (Potamotrygon castexi). Animal Cognition, 13(3), 507-513.

- Toffoli, Daniel, Tomas Hrbek, Maria Lúcia Góes de Araújo, Maurício Pinto de Almeida, Patricia Charvet-Almeida. (2008). A test of the utility of DNA barcoding in the radiation of the freshwater stingray genus Potamotrygon (Potamotrygonidae, Myliobatiformes). Genetics and Molecular Biology 31(1), 1-116.

- de Araújo, Maria, Lúcia Góes, Patricia Charvet-Almeida, Mauricio Pinto de Almeida and Henrique Pereira, Brazil. (2004). Conservation perspectives and management challenges for freshwater stingrays. Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. 14, 10-12.

- Charvet-Almeida, Patricia, Maria Lúcia Góes de Araújo, Ricardo S. Rosa and Getúlio Rincón. (2002). Neotropical Freshwater Stingrays: diversity and conservation status. Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. 14, 10-12.

- de Araújo, Maria, Lúcia Góes, Patricia Charvet-Almeida, Mauricio Pinto de Almeida and Henrique Pereira, Brazil. (2004). Conservation perspectives and management challenges for freshwater stingrays. Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. 14, 10-12.

- Charvet-Almeida, Patricia, Maria Lúcia Góes de Araújo, Ricardo S. Rosa and Getúlio Rincón. (2002). Neotropical Freshwater Stingrays: diversity and conservation status. Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. 14, 1-4.

- http://www.monsterfishkeepers.com/forums/showthread.php?t=172190

- http://fishbase.org/summary/FamilySummary.php?ID=21

- http://www.cites.org/common/com/ac/20/e20-inf-08.pdf

- http://www.raylady.com/Potamotrygon

0 Comments