Rays of the genus Potamotrygon, the river stingrays, are among the most extraordinary animals that are available to the freshwater aquarist. They are also among the most challenging to keep. While the likelihood of lasting success with these species is considerably greater than that of other rays (whether freshwater, marine or anything in between), a serious attempt to keep them should begin with a large measure of research, planning and patience. This involves:

- developing an understanding of how these highly specialized creatures have physically and physiologically adapted to their natural environment, and

- learning how to simulate this environment in a manner that meets the unique needs of each target species. With time and the necessary resources, river stingray keepers can construct a captive environment in which their animals can not only thrive, but in due course reproduce.

This piece discusses the morphology, reproduction and husbandry of the river stingrays. A previous piece discussed river stingray classification, distribution, ecology and conservation.

Morphology

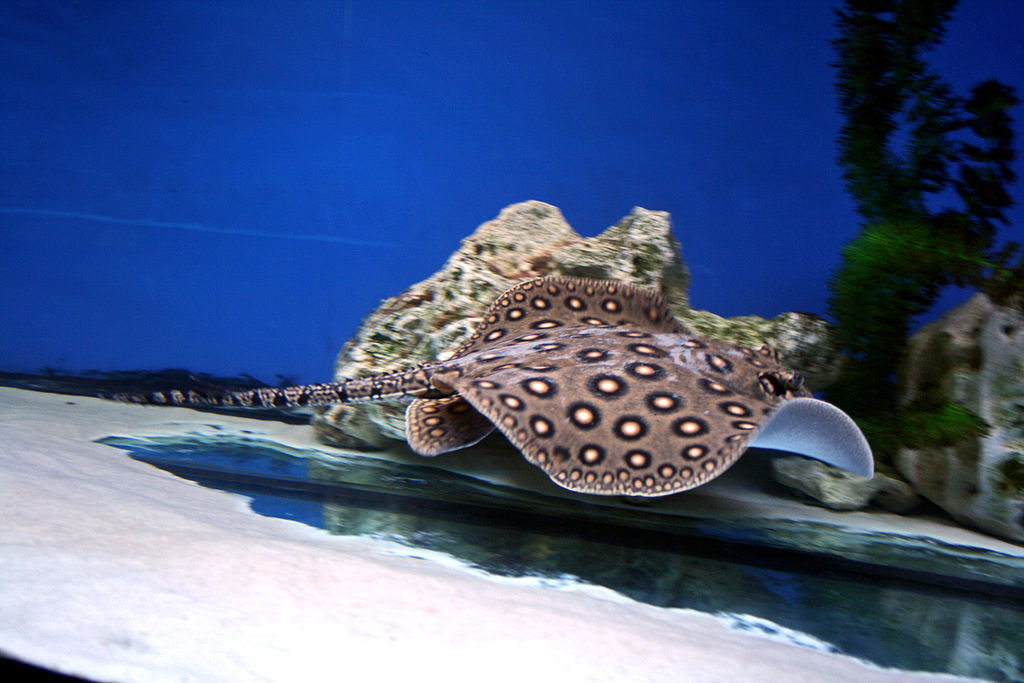

River stingrays (such as these P. motoro) require a deep bed of fine substrate. Photo by Karel Jakubec.

Species of the genusPotamotrygon are roughly average in size among the batoids (i.e., rays and skates), ranging from approximately 25 cm in disc width to 100 cm or more. The smallest species of the genus, P. scobina, reaches 20.5 to 27 cm in disc width; P. brachyura, the largest species of the genus, is known to reach a disc width of as much as 150 cm. Generally, the disc is slightly longer than it is wide. Note that disc width (or DW) and disc length (or DL) are standard measurements of stingrays. Total length is generally not used, given that a portion of the tail is often missing.

The disc is formed mainly by greatly enlarged pectoral fins, which are fused to the head. Posteriorly it overlaps most of the pelvic fins. Although there are no dorsal or caudal fins, membranous skin folds (or finfolds) are present on both the upper and lower tail midlines. Compared to other members of their family, river stingrays have a tail (or caudal appendage) that is stout and short (typically shorter than disc length). The dorsal surfaces of the disc and tail are often quite spiny, being covered with denticles, thorns and tubercles.

Small openings located on the top of the head (or spiracles) take the place of the mouth to draw water into the gill chambers while resting in the substrate. Photo by Guérin Nicolas.

Like other stingrays, fishes of this genus have venomous barbs (or caudal stings) located on the dorsal surface of their tails. Stings are hardened sections of dermal tissue with acute distal tips. They are continuously shed and replaced. An individual may bear up to four stings at a time. The sting is well developed in Potamotrygon. It is comprised of a spine, an integumentary sheath and venom glands. The spine, which gives the surface of the sting its stiffness, is composed of dentin. It contains several small, lateral serrations oriented toward the base. Special glands at the base produce venom that is carried along longitudinal grooves. When the spine is relaxed, it rests on a wedge-shaped piece of tissue that keeps it bathed in venom and mucus.

Most potamotrygonids bear highly distinctive markings. These include various spots, reticulations and ocelli under a grey, black or brown background coloration. Patterns of pigmentation are presumed to be species-specific.

Barbs on the caudle sting (as on this P. henlei) cause severe exit wounds that are highly susceptible to infection. Photo by Stan Shebs.

Reproduction

The Potamotrygonidae are similar to marine elasmobranchs in that they are characterized by late maturation, slow growth and low fecundity. The hydrologic cycle appears to exert an appreciable influence on the reproductive cycle of potamotrygonids. Studies suggest that the reproductive cycle includes a resting interval in at least some populations. As males reach spawning condition, they begin to seek out and chase females. Courtship can become violent, particularly if a chosen female is unreceptive to a male’s advances; males will resort to biting and wrestling in order to assume a belly-to-belly position. Copulation transpires quickly, with the male inserting a clasper into the female’s cloaca and releasing milt. If a successful fertilization occurs, the oviduct undergoes changes that allow it to function as a uterus.

Just after birthing, females may be removed from a breeding group for a recovery period. Photo by Steven G. Johnson.

All known freshwater stingrays employ a reproductive strategy called matrotrophic viviparity, wherewith uterine milk (or histotrophe) secreted by specialized uterine filaments (or trophonemata) nourishes the developing embryo during gestation. Gestation may take place either intermittently or throughout the year. The gestation period is variable among wild populations, lasting from 3-12 months; however, in captive populations, this stage generally lasts from 9-12 months. The birthing season can last from 3-4 months. Depending upon species, environmental conditions and the fitness of the mother, the number of offspring produced from each gestation is usually from 2-7, though litters as large as 15 have been reported. The pups are born live and are fully formed. In captivity, pups are best transferred immediately after birth to a dedicated system for solitary grow-out. Absorption of the yolk sac lasts up to 7 days. By this time, pups can be offered a variety of live and frozen foods. With proper nutrition, excellent water quality and ample living space, growth is rapid.

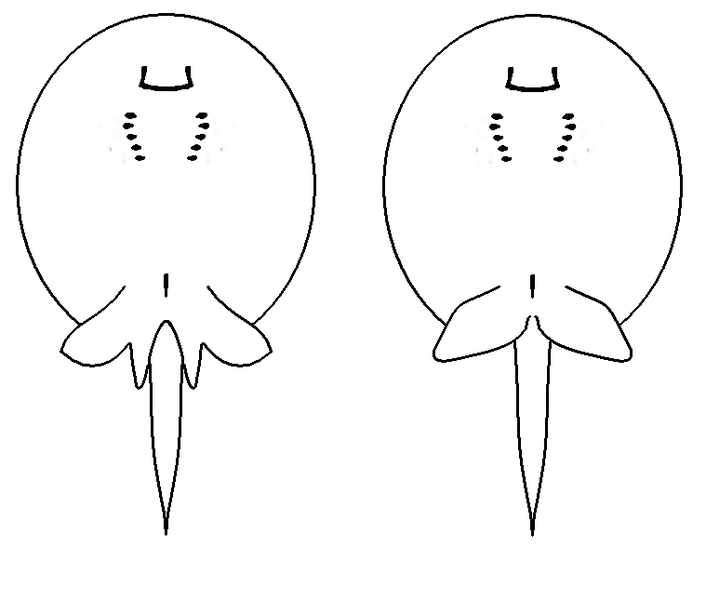

Sexing adult river stingrays is uncomplicated; as in other chondrichthyans, males (left) can be identified by the presence of claspers on their pelvic fins. Illustration by Rafael Ruivo.

Husbandry

One of the most important elements of a river stingray aquarium is the tank itself. Here, the best tank is a big tank. Some sources recommend minimum tank volumes of 90 gallons. Even so, one would do best to use a volume of 120 gallons or more. A “long” tank is preferable to a “tall” tank, as the inhabitants will make better use of horizontal (i.e., bottom) space than vertical space. Thus, even the smaller species need a minimum tank size of 48 in long x 30 in wide x 20 in tall per trio (i.e., one male and two females).

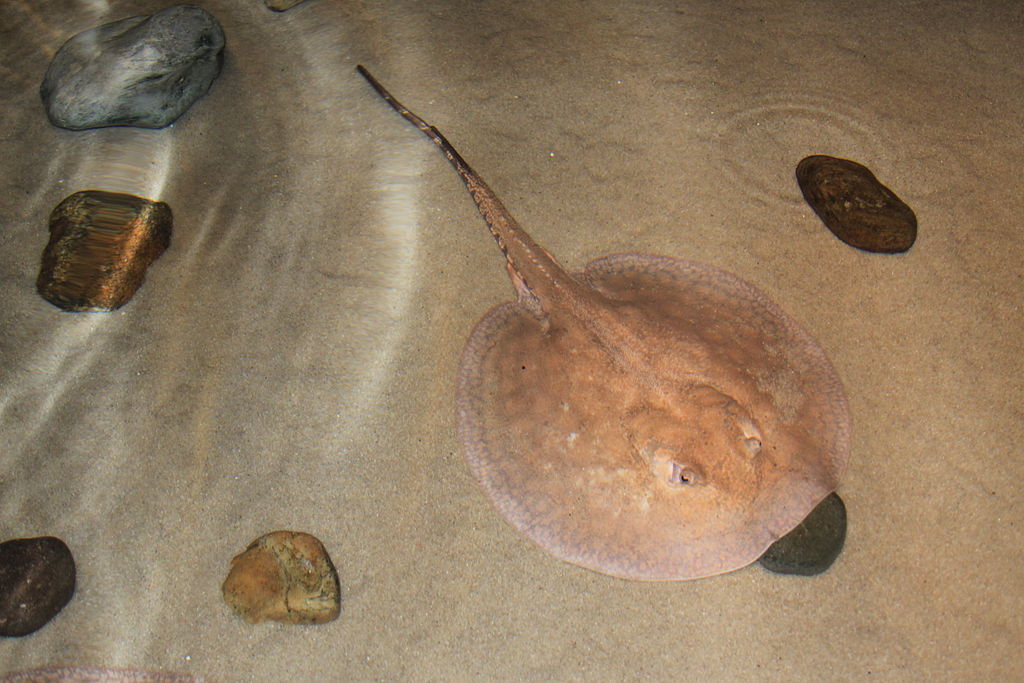

A river stingray aquarium should have a sandy substrate. The sand bed should be deep enough that the rays can completely bury themselves (i.e., such that only their eyes will be visible).

Sub-gravel heaters should never be used, as they may burn the animal. Conventional heaters (either submersible or non-submersible) should instead be used, albeit with a protective cover (such as a Hagen® heater guard).

Because river stingrays (such as this P. leopoldi) have relatively small mouths, some food items are best chopped down to a manageable size. Photo by Noel Weathers.

As river stingrays are somewhat sensitive to suboptimal water conditions, they require highly effectual water treatment/filtration. Only an efficient biofilter (such as a trickle filter with high surface area media) should be relied upon to carry out biofiltration. Aggressive mechanical filtration (and frequent cleaning of sponges/pads) is advisable, as rays can be unusually messy eaters. Chemical filtration (particularly those types that remove metals) can be very useful in protecting the animals from contaminants and bioaccumulations.

River stingrays are not especially territorial; provided that a large enough aquarium is used, they may be kept in groups or with certain other types of fish. They cohabitate especially well with surface dwelling fishes such as gars, which tend to stay out of their way. They should not be housed with aggressive or nippy fishes such as piranhas, puffers and certain cichlids. Caution should be exercised if they are to be housed with plecos (e.g., Plecostomus sp.), which tend to irritate them by sucking at their disc. While fast and flighty little fishes such as tetras will generally be safe, river stingrays will eat any small fish that they can catch.

It is said that South American natives fear stingrays (such as this P. hystrix) more than they do the piranha. Photo by Jim Capaldi.

River stingrays benefit from a highly varied diet. They may be offered some combination of live items such as blackworms, earthworms (chopped), bloodworms, ghost shrimp and/or grass shrimp, with frozen items such as clam, mussel, silversides, krill and/or mysis shrimp.

Great care must be taken at all times when handling stingrays. It is far more preferable to capture them with a bucket or bowl than with a net. Never lose sight of these animals when handling or working around them. River stingray injuries are extremely painful and potentially life threatening. If a blood vessel is punctured, apply hard pressure directly to the wound to minimize any bleeding. The affected area should immediately be placed under water that is as hot as the victim can tolerate. After most of the pain has subsided, the wound can be cleaned by way of Betadine™ treatment followed by a rinse with disinfectant soap. Then–no matter how minor the injury appears to be–seek immediate medical attention. The examination should include radiology to locate any fragments of the sting that may be embedded in the wound. Return to the physician at the first sign of any infection.

Though river stingrays are not a major target of the ornamental fishery in the State of Amazonas, they are credited with helping to increase sales of the cardinal tetra (Paracheirodon axelrodi). Photo by Axel Rouvin.

Conclusion

Stingrays of the genus Potamotrygon can be stunning aquarium animals. While they have a much better record of captive survivability than other batoids, their husbandry is hardly undemanding or uncomplicated. In actual fact, properly caring for these unusual creatures requires a considerable amount of preparation and resources. Moreover, one must take precautions to avoid serious injury while handling or working around them. Still, a healthy river stingray is an exceptionally fascinating, beautiful creature and is definitely worth the extra effort. The relative ease with which Potamotrygon spp. can be successfully bred and reared makes them even more appealing. Breeding river stingrays is not only an interesting (and potentially very lucrative) activity, but is also important for conservation efforts in that it reduces demand for wild-caught specimens. With growing commercial production, one could hope that more river stingray species and varieties may be available to home aquarists in the very near future.

Sources

- Kuba, Michael J., Ruth A. Byrne and Gordon M. Burghardt. (2010). A new method for studying problem solving and tool use in stingrays (Potamotrygon castexi). Animal Cognition, 13(3), 507-513.

- Toffoli, Daniel, Tomas Hrbek, Maria Lúcia Góes de Araújo, Maurício Pinto de Almeida, Patricia Charvet-Almeida. (2008). A test of the utility of DNA barcoding in the radiation of the freshwater stingray genus Potamotrygon (Potamotrygonidae, Myliobatiformes). Genetics and Molecular Biology 31(1), 1-116.

- de Araújo, Maria, Lúcia Góes, Patricia Charvet-Almeida, Mauricio Pinto de Almeida and Henrique Pereira, Brazil. (2004). Conservation perspectives and management challenges for freshwater stingrays. Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. 14, 10-12.

- Charvet-Almeida, Patricia, Maria Lúcia Góes de Araújo, Ricardo S. Rosa and Getúlio Rincón. (2002). Neotropical Freshwater Stingrays: diversity and conservation status. Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. 14, 10-12.

- de Araújo, Maria, Lúcia Góes, Patricia Charvet-Almeida, Mauricio Pinto de Almeida and Henrique Pereira, Brazil. (2004). Conservation perspectives and management challenges for freshwater stingrays. Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. 14, 10-12.

- Charvet-Almeida, Patricia, Maria Lúcia Góes de Araújo, Ricardo S. Rosa and Getúlio Rincón. (2002). Neotropical Freshwater Stingrays: diversity and conservation status. Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. 14, 1-4.

- http://www.monsterfishkeepers.com/forums/showthread.php?t=172190

- http://fishbase.org/summary/FamilySummary.php?ID=21

- http://www.cites.org/common/com/ac/20/e20-inf-08.pdf

- http://www.raylady.com/Potamotrygon

0 Comments