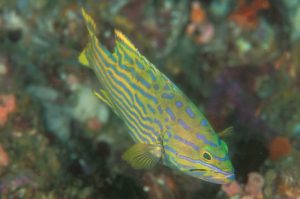

Izu hogfish (Bodianus izuensis) – this deepwater labrid from southern Japan and teh Phillipines is a durable aquarium inhabitant.

Creating a deep-water reef aquarium can be both exciting and challenging. Except for the lighting system, there is little difference between the equipment and aquarium care involved in setting-up and maintaining a deep-water and a shallow-water reef aquarium. The biggest difference between these two biotope aquariums is their inhabitants. Finding organisms that are more indicative of deep reef environments can be more of a challenge and tend to be more expensive.

In the last issue of Advanced Aquarist we began our examination of deep reef fishes. I pointed out that the term “deepwater reef fish” is somewhat arbitrary and, for our purposes, decided to define a deepwater coral reef fish as a species that is most abundant in coral reef habitats at depths in excess of 100 feet.

In this article, I would like to continue our survey of some fish families that are both of interest to aquarists and that contain representatives that occur in deep reef environments. Note that not all the fishes discussed below are suitable for the reef aquarium. I will point out those species that may harm ornamental invertebrates.

Spanish flag (Gonioplectrus hispanus) juvenile – a true deep reef inhabitant, this species is typically collected at depths in excess of 200 feet (as a result it commands a high price).

Grammas

Most of the fishes that belong to this family are found in deep water. In fact, the majority of members from the most specious genus, Lipogramma, are limited to depths in excess of 200 feet. One of these, the heliotrope basslet (Lipogramma klayi) is occasionally available to hobbyists. This fish is most common on talus, or rubble slopes. It hovers over the bottom and feeds on zooplankton. The heliotrope basslets are engaging aquarium fish, but often ship poorly. They should be kept in a tank with peaceful tankmates. More then one L. klayi can be kept in the same tank, although make sure there is enough space and shelter to go around.

One of the most common deepwater Gramma spp. in the aquarium trade is the blackcap basslet (Gramma melacara). In certain parts of the tropical western Atlantic this is the most common fish species found on reefs at depths between 160 to 325 feet. The dusky gramma (Gramma linkii) is a deepwater form that is found at a minimum depth of 90 feet (it is most common at depths in excess of 195 feet). Like it shallow water cousin, the royal gramma (Gramma loreto), G. linkii is a durable aquarium fish, although it tends to be more aggressive towards conspecifics and related forms. Both the Lipogramma and Gramma spp. are great reef aquarium fishes.

Yellowtail reef basslet (Liopropoma sp.) – collected individuals often suffer from swim bladder injuries.

Tilefishes

There are a number of sand tilefishes (Hoplolatilus spp.) that are found on deep reef sand slopes. Some of these regularly enter the aquarium trade. These include the flashing tilefish (Hoplolatilus chlupatyi), the (H. cuniculus), the skunk tilefish (H. marcosi), the purple tilefish (H. purpureus), and the blueface tilefish (H. starcki). These species are most abundant at depths in excess of 100 feet.

Unfortunately the majority of tilefishes fare poorly in captivity. Therefore, I would only recommend them to more experienced aquarists. One problem these flighty fish present, is that they will jump out of the open aquarium, or even through small openings that may be present with a covered tank. So what’s the problem? Just make sure the entire tank is covered! Well, the problem is that these fish will still try and jump out if startled and often cause themselves lethal injuries when they catapult themselves against the hard aquarium top. The best way to prevent these maladies is to provided plenty of suitable hiding places (e.g., burrows under rocks lying on a sandy bottom), to gradually extinguish aquarium and room lighting, and to keep a dim night light on over the tank.

Tilefish often suffer from injuries associated with their being brought to the surface from depth. If not properly decompressed their swim bladders can be damaged and they will have difficulty maintaining their position in the water column. These individuals usually swim incessantly, with their tails positioned high above their heads as they swim. The tilefish will not harm sessile invertebrates and most are no threat to ornamental crustaceans.

Butterflyfishes

One of the best known groups of deep-water butterflyfishes constitute the subgenus Roa. This group contains eight species, most of which are restricted to depths in excess of 100 feet. All of these fishes readily acclimate to aquarium living and make attractive additions to the deepwater fish tank. Because of their propensity to pick at coral polyps, they are not recommended for the reef aquarium. (Some have been successfully housed with some of the toxic soft corals, but it is a risky proposition to house them with cnidarians.)

The best known member of the subgenus Roa is Tinker’s butterflyfish (Chaetodon tinkeri). This fish is found on deep reefs around the Marshall, Hawaiian, and Johnston Islands and have been reported from depths of about 90 to over 430 feet. However, it is rarely encountered at depths of less then 130 feet. The Burgess butterflyfish (Chaetodon burgessi) usually resides along precipitous drop-offs, at a depth range of 130 to 260 feet. These two species are some of the hardiest of all the chaetodontids. The headband or Indian butterflyfish (Chaetodon mitratus) member of this subgenus and it too is found in deep-water. It is most common at depths in excess of 160 feet and usually lives under overhangs and in caves. It is occasionally seen in the aquarium trade, but because of its deep-dwelling habits and its Indian Ocean distribution it commands high dollars. Those that decide to invest in one of these beauties will be glad to now it is a durable aquarium fish. The rarest member of this group is the yellow-crowned butterflyfish (Chaetodon flavocoronatus), which is known to occur around the Marianas Islands. Those individuals that are collected usually go to Japan.

The members of the subgenus Roa are not the only deep-water butterflyfishes. There are a number that are rarely seen by aquarists and scientists alike, unless you have a deep sea submersible. There are others, however, that do make their way into aquarium stores. For example, the common reef butterflyfish (Chaetodon sedentarius) of the Atlantic is most abundant at depths greater then 170 feet in certain parts of its range, while the bank butterflyfish (Prognathodes aya) is usually found at depths in excess of 150 feet. The Caribbean longsnout butterflyfish (Prognathodes aculeatus) is sometimes observed in shallow water, it reaches its peak of abundance at depths in excess of 100 feet. All of these are hardy, durable chaetodontids that fare well in a variety of different situations.

Pugnose bass (Bullisichthys caribbaeus) – this rare serranid is usually found at depths of 300 feet or more and rarely makes it into the aquarium trade.

Angelfishes

There are also a number of pygmy angelfishes that typically inhabit deep reef habitats. These include Colin’s angelfish (Centropyge colini), the blue Mauritius angelfish (C. debelius), the multicolor angelfish (C. multicolor), Nahacky’s angelfish (C. nahackyi) and the multibarred angelfish (Paracentropyge multifasciata). These angels are found in caves on deep reef drop-offs, or among coral boulders and rubble. Like many other deep water fishes check these fish carefully for decompression related maladies. In an occasional specimen, the fish’s side will turn red, swell and then burst open. This apparent infection may be related to improper decompression.

The two most spectacular deep water members of this genus are the narcosis (Centropyge narcosis) and Boyle’s or the peppermint angelfish (Paracentropyge boylei). These two fish were discovered off the island of Rarotonga, in the Cook Islands, in this decade by Richard Pyle and Chip Boyle. The peppermint angelfish is found on rubble slopes or on drop-offs at depths of 180 to 390 feet. Although the pygmy angelfishes can be kept with sessile invertebrates many will eventually nip at corals, which can lead to the demise of certain cnidarian species. So beware that there is always a risk when introducing pygmy angels to your reef aquarium.

The bandit angelfish (Apolemichthys arcuatus) is usually encountered at depths of 100 feet and is endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. Unfortunately, this sponge-eater is difficult to keep. Occasionally, you will find an individual that readily accepts captive fare, but these individuals are rare.

The angelfish genus Genicanthus is well represented in deep reef habitats. This genus is comprised of 10 planktivorous species that spend much of their time swimming above the reef where they capture their prey. Because of their food habits, these fishes are well-suited to the reef aquarium. They should, however, be fed a nutrient rich food at least twice a day. While most members of this genus are found at lesser depths, there are a number of Genicanthus spp. that are most abundant at depths in excess of 100 feet. For example, the ornate angelfish (Genicanthus bellus) is typically found at depths in excess of 160 feet. This is not as durable as some of its more shallow water congeners (e.g., Lamarck’s angelfish, Genicanthus lamarcki). Make sure an ornate angelfish is swimming properly before you buy it. If it swims in a head-down manner and has a hard time maintaining its position in the water column, it may be suffering from swim bladder problems.

Damselfishes

The family Pomacentridae contains a number of fishes that are possible candidates for deep water reef aquariums. The majority of deep-water damsels belong to the genus Chromis. These are zooplankton-feeders that often occur in groups that mill in the water column when foraging. In the Caribbean the Caribbean chromis (Chromis enchrysura), the sunshine fish (C. insolata), and purple chromis (C. scotti) are found on fore reef slopes and drop-offs. All of these fishes are more passive then many of the other damselfishes and are ideally-suited for the Caribbean deep reef community tank. In the Indo-Pacific, the whitetail chromis (Chromis leucura), the yellow chromis (C. analis) and the deep-reef chromis (C. delta) are usually found on the deep-reef. These species are less common in the aquarium industry than their Atlantic counterparts. Most of the Chromis spp. can be kept in groups in the aquarium, although they often form a pecking order. If a captive group is not comprised of enough individuals, the subordinates may be picked on incessantly and perish as a result.

There are also two species in the genus Chrysiptera that are more abundant in deep-water. These two beautiful species are Starck’s demoiselle (Chrysiptera starcki) and the blueline demoiselle (C. caeruleolineata). The former has been showing up in the aquarium trade with some regularity in recent months. I have found C. starcki to be relatively passive, at least juveniles and young adults. Large adults may cause some problems if kept in a small tank with more passive species. Only one C. starcki should be housed per tank.

Wrasses

The wrasses comprise the second largest family represented on coral reefs. It is not surprising that there are quite a few labrids that lurk on the deep reef. In the western Atlantic the Cuban or spotfin hogfish (Bodianus pulchellus) is usually found at depths of 50 to 400 feet, while the rarely seen red hogfish (B. puellaris) occurs at a depth range 60 to 900 feet. Juvenile Cuban hogfish spend much of their time cleaning parasites and dead tissue off of other fishes.

Coral Sea or rosy fairy wrasse (Cirrhilabrus bathyphilus) – a deepwater species that is readily collected in Vanuatu.

There are also deepwater hogfishes in the Indo-Pacific. One of the most spectacular species is the red-striped hogfish (Bodianus opercularis). Unfortunately, this species is rarely observed in the aquarium trade. There is a closely related, but undescribed form, that shows-up more often then B. opercularis. It differs in having a black area on the caudal peduncle and on the anterior portion of the caudal fin. There is a white semicircular margin along the posterior edge of this black area. Both the red-striped hogfish, which is only found in the Indian Ocean and Red Sea, and its Pacific look alike, are found on steep reef walls. I have kept the Pacific redstriped hogfish and found it to be a great display animal that readily adjusts to captive life. Although it will ignore dissimilar species, it may chase other wrasses that have like-shape. It is also possible that larger individuals may eat small bivalves and crustaceans, including ornamental shrimp. However, I have kept it with cleaner shrimps without incident (I did have one bite off the legs of a newly molted banded coral shrimp).

The twinspot hogfish (Bodianus bimaculatus) is another deep-water hogfish that is a resident of sand slopes with scattered boulders, fore reef slopes and drop-offs. It is found at depths from 66 to 198 feet, but is most common in water deeper than 132 feet. This is a great aquarium fish. It will readily acclimate to life in captivity and its diminutive size makes it one of the best hogfish for the aquarist with a smaller tank. Although juveniles do best if housed with non-aggressive tankmates, as this species grows it will become more boisterous, and may bully, smaller more docile fish tankmates.

Some of the members of the genus Cirrhilabrus, which are known commonly as fairy wrasses, are also found in deep reef habitats. They typically occur in rubble areas or among patches of macroalgae. The deep water forms include the flame or Jordan’s fairy wrasse (Cirrhilabrus jordani), lined fairy wrasse (C. lineatus), rhomboid fairy wrasse (C. rhomboidalis), and the redmargined fairy wrasse (C. rubrimarginatus). These wrasses are wonderful reef tank residents. The biggest challenge to their long-term care is keeping them in an open aquarium (they often jump from uncovered tanks or even through small holes in the aquarium top). Larger individuals are also likely to suffer from shipping stress and regularly rub the skin off their snouts and upper jaws when confined in a shipping bag. These injuries can function as a site for bacterial or viral (e.g., Lymphocystis) infection. As a result, smaller Cirrhilabrus are often more desirable.

In the last few years that whitebarred or mystery wrasse (Pseudocheilinus ocellatus) has been appearing in some aquarium stores. This magnificent fish is common at depths greater then 100 feet.

Firefishes

These small, elongated fish are great additions for the passive community tank. They are extremely hardy, colorful, eat most foods, and are disease resistant. The biggest problem is their habit of jumping out of the aquarium. There are two species of firefish that are commonly found in deep-water reef habitats. Although they are sometimes found in groups in the wild, firefishes tend to fight in aquarium confines. As a result, they are best kept singly or in male-female pairs. They should be provided with rubble or some other benthic structure that they can shelter under. All of the firefish are highly disease resistant and a great choice, even for the neophyte saltwater hobbyists.

Harlequin hind (Cephalopholis polleni) – this species is usually found singly or in pairs inhabiting caves in deep reef walls.

The purple firefish (Nemateleotris decora)is probably the most spectacular member of the genus. It is found at depths ranging from 60 to 230 feet, but is most common deeper than 90 feet. The purple firefish is usually found within 20 inches of the bottom, facing into the current to intercept passing zooplanktors. It is found singly or in pairs.

Helfrich’s firefish (Nemateleotris helfrichi) is the most difficult member of the genus to acquire, mainly because it is most abundant at greater depths than its congeners. This splendid species occurs at a depth range of 80 to 270 feet, but is not common at less than 150 feet. It lives over sand and mixed sand and rubble patches, on steep slopes, walls or at the base of reefs. This is a hardy aquarium fish that can be kept in a peaceful, fish-only aquarium, or in a shallow or deepwater reef tank. However, it will acclimate more quickly in the low light conditions, characteristic of its natural habitat. Helfrich’s firefish will accept most aquarium foods and, like its relatives, it has a proclivity to jump out of an open aquarium and into overflow boxes.

This ends our examination of some deep-water reef fishes. There are many other coral reef fishes limited to deeper reef slopes, but I have tried to point-out some of the species that are available to aquarists. If you are an aquarist that is interested in replicating a piscine assemblage from a specific habitat, the deep-water reef fish community, you should consider creating a deep-water reef fish community in your home aquarium. It is worth the extra effort and added expense!

References

- Michael, S. W. 1998. Reef Fishes. Volume 1. TFH Publications, Neptune, NJ, 624 Pp.

0 Comments