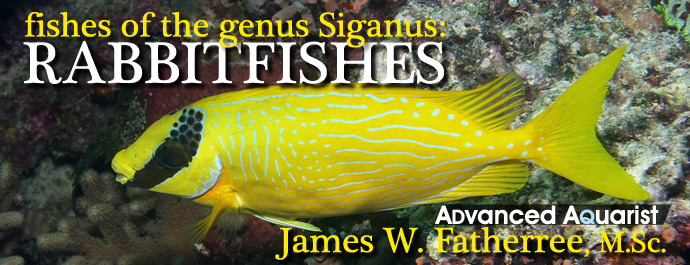

The genus Siganus is comprised of 26 or 27 species of fish and a couple of hybrids, depending on who you ask, all of which are commonly known as rabbitfishes. Also called spinefoots by some, these can make great additions to appropriately-sized aquariums and are well worth a look, as they’re generally attractive, relatively peaceful, and easy to care for. They also tend to be great algae-eaters, and are typically much hardier than the ever-popular surgeonfishes. So, this month I’ll give you some information about the genus as a whole, the species commonly offered in the hobby, and how to take good care of them.

Supposedly, the rabbit name was given to these fishes for being docile grazers with dark eyes and a small mouth, with the foxface rabbits having stripes on their faces and relatively long snouts. That doesn’t look much like a rabbit’s mouth or a fox’s face to me, though…

To start, there’s sometimes a bit of confusion about the rabbitfishes’ names due to the fact that five of the Siganus species used to be placed in the genus Lo. The latter is no longer a separate genus though, and is instead considered to be a sub-genus within Siganus. These five species are Siganus magnificus, S. niger, S. vulpinus, S. unimaculatus, and S. uspi, but you can still find them being called Lo magnificus, etc. from time to time. Really, the only obvious distinctive feature these species share is that they all have a somewhat elongated snout relative to the others (Woodland, 1990), and are oftentimes called foxfaces, or foxface rabbitfishes. Rabbit, spinefoot, and foxface, ohhhhh the names people come up with for fishes at times…

Anyway, aside from their names, there’s something else quite unique about siganids, as they’re one of the few types of venomous fishes that oftentimes end up in aquariums. They all have venom glands associated with the spines in their fins, and if you get stuck by one it’s going to hurt very badly.

Watch out for those fins! All rabbitfishes can deliver a very painful dose of venom as a means of self-defense.

If cornered, panicked, or handled improperly (with your hands), they can give you a painful reminder that they’re venomous, but fortunately it won’t kill you unless maybe you happen to have some unusual allergic response to the venom or get a mortal infection of the wound. However, after doing a thorough online search I wasn’t able to find any reports of this happening. In fact, I wasn’t able to find a single case of someone being hospitalized after being spiked, either.

Regardless, there are a couple of things to do if envenomated by a rabbitfish, one of which is getting professional help. I realize I’ve just pointed out that the chances of receiving a serious injury are slim, but that’s if an envenomation is treated properly. Avoiding professional help or neglecting such an injury can be very painful and might lead to real trouble. So, a trip to the doctor is still highly recommended.

Still, before you head out the door, note that applying some hot water therapy can help to relieve the pain almost immediately. The venom is a heat-labile protein, which means it can be broken down very effectively by exposure to heat (Meier & White, 1995). So, you can soak or bathe the injured body part in water that’s as hot as you can stand in order to reduce/eliminate the venom’s effects. This is normally around 110° to 115°F, but should not be any hotter as you’ll risk scalding yourself and making matters worse.

Of course, the sooner you can get to a doctor the better, and upon arrival it’s important to report exactly what kind of fish got you. You shouldn’t assume that a doctor knows what a rabbitfish is though, so explain if necessary. Then, you’ll likely receive a continuing hot-water treatment for 30 to 90 minutes, and may get a shot of anesthetic if the pain is severe. The wound should be elevated to help reduce any swelling, too.

Now you might think that you can do this yourself (you can), but in all cases where a skin-breaking wound is caused by a marine organism, tetanus prophylaxis (like a shot) is required if not already up to date. It is well documented that tetanus has caused deaths following marine organism-related penetrating wounds. Numerous other infections can also occur in conjunction with such wounds, including Vibrio in rare cases. So, I can’t say it enough, be mindful of the possibility of these after-effects of an envenomation.

Because the potential for infection is relatively high, your doctor may also use various antibiotics as part of the treatment. This is especially so if an infection appears some time after the initial injury has occurred. Of course, if you don’t get your hands too close to an unhappy rabbitfish, you don’t have to worry about any of this.

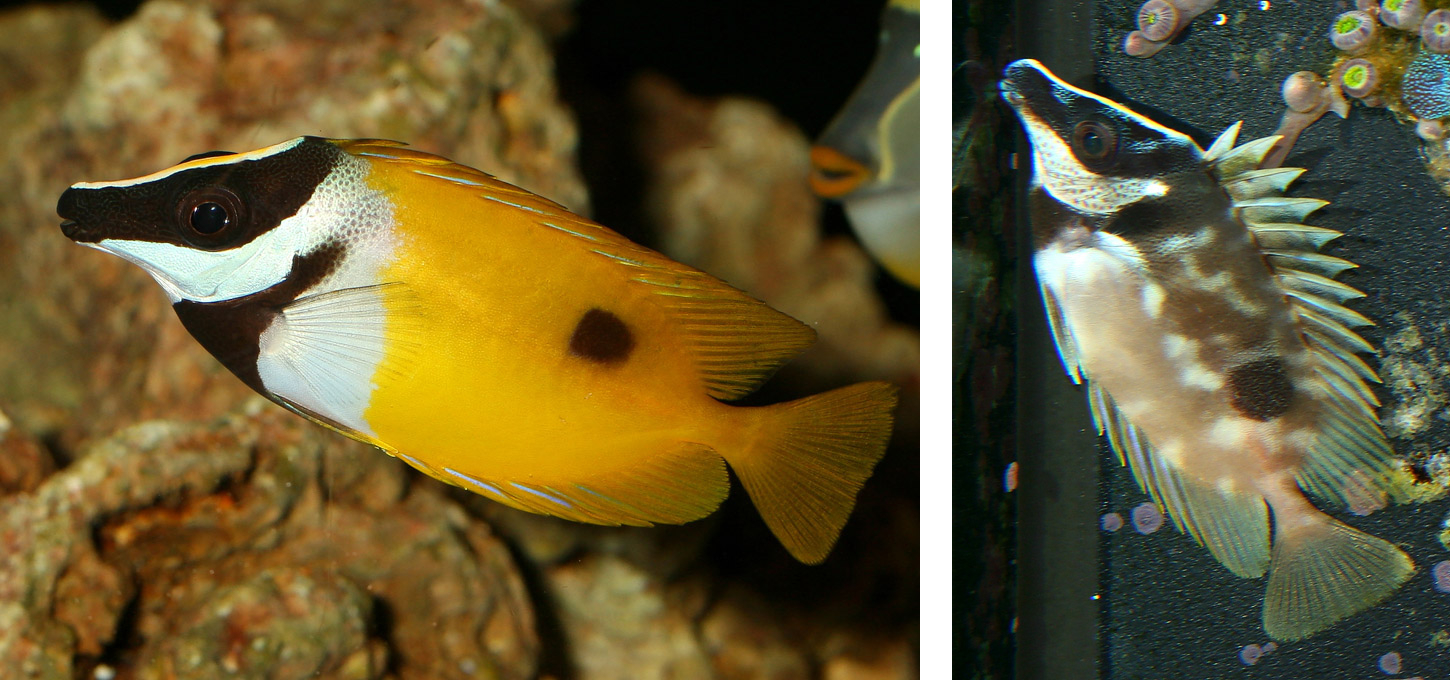

Next, is the rabbitfishes’ ability to camouflage themselves as another means of staying alive. All of them can dramatically change their appearance at will, and typically do so when sleeping or when frightened. Regardless of their “normal” overall coloration, which is often quite bright, they can lose it and take on a splotchy appearance that’s not colorful at all and often looks more like military camo. When hiding out, especially in rockwork and in the branches of corals, these patterns can be very effective and do quite a good job of making the fishes more difficult to see. So, don’t automatically be alarmed if you use a flashlight to look in your aquarium when the lights are off (like I do regularly) and can’t seem to find one.

Lastly, these are all primarily algal grazers. However, many will also eat some meaty food items, as some will include tunicates, sponges, and corals in their diets. Yes, corals. I’ll provide some more specific information about their diets in a minute, though.

Lastly, these are all primarily algal grazers. However, many will also eat some meaty food items, as some will include tunicates, sponges, and corals in their diets. Yes, corals. I’ll provide some more specific information about their diets in a minute, though.

And with that covered, let’s look at the species I’ve encountered in shops. I’ve provided some basic information for each, including their maximum sizes, geographic ranges, and habits/habitats as reported by Fishbase (undated) and Woodland (1990). Do keep in mind that maximum reported sizes are basically record-setters, so very few individuals of a species will closely approach it.

Commonly offered species:

Siganus vulpinus:

This species is commonly called the foxface rabbitfish, and is the most commonly-offered species of the group. It can reach a maximum length of almost ten inches, but is more commonly less than eight inches. It also has a broad distribution, being found in the Philippines, Indonesia, New Guinea, the Great Barrier Reef, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, the Caroline Islands, the Marshall Islands, Tonga, and Kiribati. Juveniles live in large schools around reefs, but adults live in isolated pairs or sometimes singly.

This species is commonly called the foxface rabbitfish, and is the most commonly-offered species of the group. It can reach a maximum length of almost ten inches, but is more commonly less than eight inches. It also has a broad distribution, being found in the Philippines, Indonesia, New Guinea, the Great Barrier Reef, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, the Caroline Islands, the Marshall Islands, Tonga, and Kiribati. Juveniles live in large schools around reefs, but adults live in isolated pairs or sometimes singly.

Siganus unimaculatus:

This species is called the one-spot foxface or blotched foxface, and it looks identical to S. vulpinus with the exception of having a single black splotch on either side of its body below the dorsal fin. It can also grow to a maximum length of about eight inches, and is found around the Philippines, Western Australia, and the Ryukyu Islands. And again, juveniles live in large schools, but adults live in isolated pairs.

The only other thing to say here is that this might not be a species. According to Kuriiwa et al. (2007), S. unimaculatus is actually the same species as S. vulpinus, but it sometimes has the black splotch in particular geographic localities. That’s why I said there are 26 or 27 species depending on who you ask.

Siganus corallinus:

This species is commonly called the coral rabbitfish or blue-spotted spinefoot, and can grow to a maximum length of almost fourteen inches making it one of the bigger rabbitfishes. Still, it’s most commonly less than eight inches in length, and can be found around Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Viet Nam, the Philippines, Palau, Kiribati, Papua New Guinea, Australia, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, and around the Solomon Islands, the Ryukyu Islands, the Ogasawara Islands, the Aldabra Islands, the Seychelles, the Maldives, and in the Andaman Sea. The juveniles are typically found in small schools around reefs and seagrass beds, but adults usually live in isolated pairs around shallow coral reefs. Juveniles may also school with other species, such as S. puellus.

Siganus punctatus:

This rather large species is commonly known as the gold-spotted rabbitfish or gold-spotted spinefoot, and can reach a maximum length of almost sixteen inches with most individuals staying under twelve. And, it can be found around the Philippines, Australia, Indonesia, Singapore, Taiwan, Palau, the Ryukyu Islands, the Ogasawara Islands, the Mariana Islands, the Caroline Islands, and the Kapingamarangi Islands, as well as the eastern edge of the Indian Ocean, the Gulf of Thailand, and the South China Sea. This species also schools in shallow estuaries when young, but is found in isolated pairs in lagoons and on deeper reefs when mature.

Siganus uspi:

This smaller species is commonly known as the bicolored foxface or uspi rabbitfish, and reaches a maximum length of about nine and a half inches. Unlike many of the other species, it also has a rather small geographic range, being endemic to Fiji, with a few being reported around New Caledonia. Regardless, the juveniles do live in schools with adults living in isolated pairs in deep pools inside reef crests and around drop-offs at reef edges.

This smaller species is commonly known as the bicolored foxface or uspi rabbitfish, and reaches a maximum length of about nine and a half inches. Unlike many of the other species, it also has a rather small geographic range, being endemic to Fiji, with a few being reported around New Caledonia. Regardless, the juveniles do live in schools with adults living in isolated pairs in deep pools inside reef crests and around drop-offs at reef edges.

Siganus doliatus:

This species has a lot of common names, typically being called the blue-lined rabbitfish, but also going by the names scribbled rabbitfish, pencil-streaked rabbitfish, two-barred rabbitfish, and barred spinefoot. They can reach a maximum length of almost ten inches, but like the first three species above, they’re most commonly less than eight. It can be found in the Indo-Malayan area and from Australia and Tonga north to Palau and Kosrae. Juveniles do form schools, typically in seagrass areas, and they pair up at a relatively small size. However, they may still travel in loose schools, oftentimes with other fishes, such as S. puellus, until they’re full-sized at which time they stop schooling and live as isolated pairs. Adults are typically found in deep reef lagoons and along drop-offs at reef edges.

Note that Kuriiwa et al. (2007) reported there was evidence that S. doliatus can interbreed with S. virgatus.

Siganus virgatus:

This species is typically called the two-barred rabbitfish, virgate rabbitfish, or barhead spinefoot, and can reach a maximum size of about twelve inches with most being closer to eight. It can be found around southern India, Sri Lanka, the Andaman Islands, Thailand, the southern and eastern coasts of China, Taiwan, the Ryukyu Islands, the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, and northern Australia. Small juveniles are found in small groups in mangrove areas and estuaries, sometimes entering freshwater. Larger juveniles/adults form isolated pairs and move onto costal reef flats and slopes.

Siganus magnificus:

This species is typically called the magnificent rabbitfish or the silver foxface, and can reach a maximum length of about nine and a half inches. It can be found in the Eastern Indian Ocean from Thailand, including the Similan Islands, to Java, Indonesia. Unlike many of its close cousins, the juveniles tend to live singly amongst the branches of corals, while adults form solitary pairs and may sometimes be found singly.

Siganus puellus:

This species is called the masked rabbitfish, decorated rabbitfish, and masked spinefoot, and is quite large, with a maximum length of fifteen inches. Most commonly they’re closer to ten inches, though. It’s found in the Indian Ocean around the Cocos-Keeling Islands and western Australia, and in the western Pacific from the South China Sea to the Gilbert Islands, north to the Ryukyu Islands, south to the southern Great Barrier Reef and New Caledonia, and Tonga. Juveniles form large schools, often mixing with S. corallinus, S. doliatus, and S. spinus, and are found on reef flats and in lagoons, especially in Acropora dominated areas. Adults form isolated pairs and move to deeper waters, typically along drop-offs at reef edges.

Siganus guttatus:

This species is commonly called the yellow blotch rabbitfish, golden rabbitfish, orange-spotted spinefoot, or golden spinefoot, and is another big one with a maximum size of over sixteen inches and commonly being about ten. It can be found in the Eastern Indian Ocean around the Andaman Islands and Thailand, around Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, and Viet Nam, and in the South China Sea and Pacific from the Ryukyu Islands to Taiwan, the Philippines, and Palau. It is quite different in that it is active at night, lives in schools as both juveniles and adults, and often prefers brackish waters. It commonly inhabits turbid inshore reefs and mangroves, and often enters rivers with the changing tides. Lavina and Alcala (1974) noted that it’s regularly found in areas with half the salinity of normal seawater, although it may also be found on drop-offs of inshore fringing reefs, at times.

Also note that Kuriiwa et al. (2007) reported there was evidence that S. guttatus can interbreed with S. lineatus (not covered).

Aquarium Care:

Rabbitfishes are categorically tough when it comes to dealing with disease and less-than-perfect water quality, being as hardy as any other fishes we commonly keep in our aquariums. However, it’s important to fed them well and give them the right foods. All of these are primarily algal grazers in the wild, with juveniles tending to eat smaller types of algae and adults feeding on larger and tougher seaweeds and such. However, many will also feed on a variety of invertebrates including sponges, tunicates, and corals, especially if they’re hungry and there’s no suitable algae to be found.

Thus, it’s important for you to give them plenty of plant matter in their diet, which may be primarily plant-based flake or frozen cube foods if you prefer. Spirulina flakes are also good, as is dried seaweed (nori and kombu). If you use the later, make sure to buy unseasoned types though, as you don’t want to dose your fishes with any sorts of additives, preservatives, etc. Of course, they’ll also eat meaty foods, including various types of zooplankton, brine shrimp, and bits of fish, clam, etc. So, you can obviously feed them a wide variety of foods in an aquarium. They’ll typically get some of their own food by picking at algae growing on rocks and such in aquariums, and thus can be great aquarium cleaners, too.

When it comes to eating corals, things can be hit or miss, though. While looking around online I found numerous stories of a rabbitfishes being fine in a reef aquarium for some time, even for more than two years, and then starting to eat both soft and stony corals. They oftentimes go after things like zoanthids and button polyps first, but from what I can tell, they may also fancy Acanthastrea and the branch tips of many other stony corals. Regardless, I have personally cared for at least a dozen rabbitfishes in my own aquariums and those of my customers years ago when I owned a tank maintenance business, and I never once had a problem with any of them. In fact, I’ve got a nice S. vulpinus in my own reef aquarium right now. No issues. So, I’m either feeding it everything it needs, or I’ve just gotten very lucky (again). I guess I’ll just say that if you plan on keeping one of these in a reef aquarium, be sure to keep the food coming and keep a close watch on it in case it starts eating things you don’t want eaten.

Other than that bit of advice, be sure to pay attention to the potential size of any species you may want and place it in an aquarium of appropriate size. If you were paying attention above, I’m sure you noticed that there’s a big size difference in species like S. uspi and S. guttatus, with the former being up to nine and a half inches in length and the latter being up to sixteen. So, give a specimen the space it needs.

Other than that, I guess the only other thing to recommend is having plenty of hiding places for a rabbitfish. While personalities differ, they oftentimes can be rather skittish and like to have some places to lay low and to sleep. So, you should have plenty of rockwork or other decorations that they can go to if they feel like getting out of sight.

Compatibilities:

When it comes to compatibilities, rabbitfishes will typically get along fine with anything else that’s not a rabbitfish of the same or similar species. However, you should always be aware that, like any other type of fish, each individual can have its own personality, and every once in a while even the supposedly nicest fish can become a problem.

Regardless, while juvenile rabbitfishes typically live in schools in the wild, trying to keep two or three of the same species of any of these in one tank will usually lead to fighting. It’s an odd thing, but in the confined space of a tank they just won’t get along with each other.

However, if the tank is big enough and several small individuals of similar size are added simultaneously, their schooling nature sometimes overrides their aggression and they may get along – at least for a while. In general, you’d need to add at least four or five at once, and even that won’t guarantee peace. So, I think it’s a bad idea to try this unless you’ve got a really big tank, as in at least several hundred gallons.

When it comes to adults, they should also be kept one to a tank, unless you can find a mated pair for sale. Unfortunately, I don’t recall ever seeing a pair being offered together, so that’s probably out, too. It may be possible to keep more than one if they’re very different species, but again, I wouldn’t try it unless you’ve got a really big aquarium. So, it’s pretty much always going to be one to a tank.

And with that, I’ll sign off…

References/sources for more information:

- Allen, G. et al. 2003. Reef Fish Identification: Tropical Pacific. New World Publications, Jacksonville, FL. 480pp.

- FishBase Global Information System. URL: www.fishbase.org/home.htm

- Kuiter, R.H. and Debelius, H. 2001. Surgeonfishes, Rabbitfishes and Their Relatives. TMC Publishing, Chorleywood, UK. 208pp.

- Kuriiwa, K. et al. 2007. Phylogenetic relationships and natural hybridization in rabbitfishes (Teleostei: Siganidae) inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA analyses. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution: 45(1).

- Lavina, E.M. and Alcala, A.C. 1974. Ecological studies of Philippine Siganid fishes in southern Negros. Sillman Journal. 21:191-210.

- Meier, J. and White, J. 1995. Handbook of Clinical Toxicology of Animal Venoms and Poisons. CRC Press. 752pp.

- Vanstone, W.E. and Turnbull, D. 1981. Siganidae (the rabbitfish): A bibliography. International Development Research Centre. Vancouver, Canada. 16pp.

- Woodland, D.J. 1990. Revision of the fish family Siganidae with descriptions of two new species and comments on distribution and biology. Indo-Pacific Fishes 19. 136pp.

You seem to have the magnificent rabbitfish label on a picture of a barred spinefoot rabbitfish (siganus doliatus), otherwise, good article.