The Amphiprion genus continues to offer some of the most well-loved and sought after species for the marine tank, and is ideally suited for commercial and hobbyist scale captive breeding, The genus contains some real beauties from Mother Nature’s stable as well as some captive bred morphs that divide opinion on occasion.

If we combine the genus’ usual good nature (through a pair can be very territorial) and ease of propagation in captivity, then no wonder the group is so well represented in aquaria and LFS across the world. There are though, a few rarities that are rarely imported and not yet commonly bred, one such species is Amphiprion chrysogaster the Mauritian Clownfish.

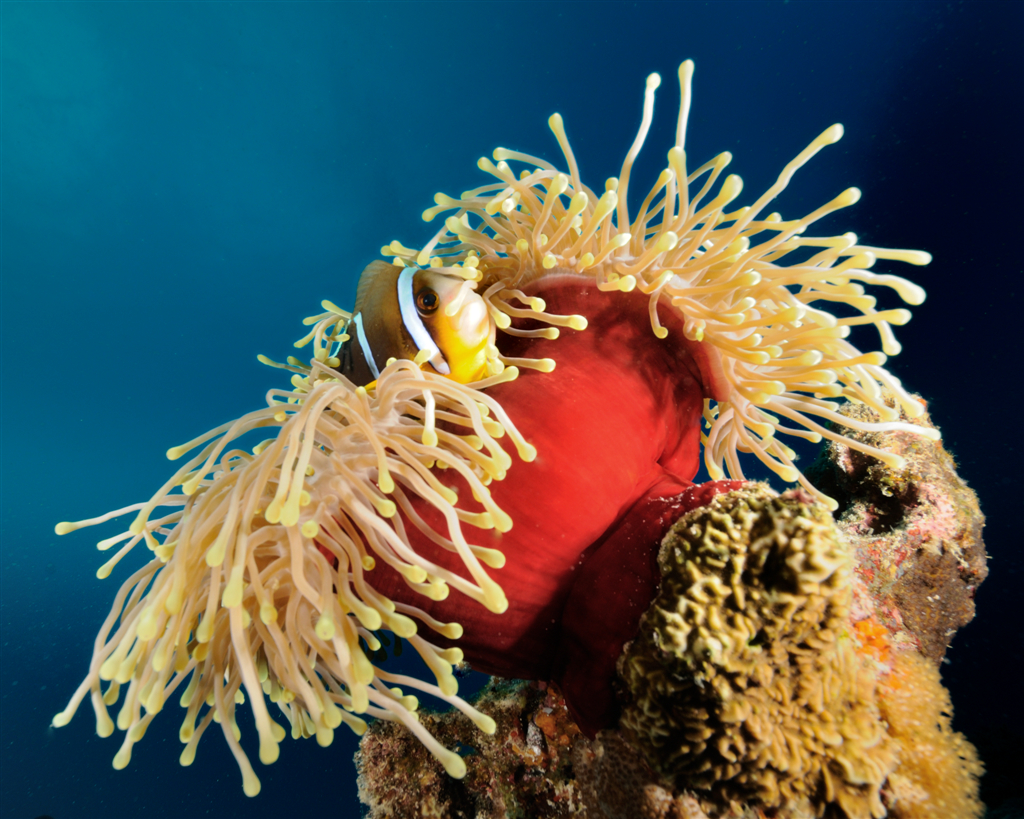

Chrysogaster sits within the Clarkii complex of clowns and is very similar to clarkii, sebae and allardi for example, though its limited geographical range makes for easy identification in the field. The fish reaches 15cm in length and can be recognised by the black tail with white upper band and white stripe to the upper rear portion of the dorsal. Juvenile specimens are much lighter in colour and present difficulties to easy identification.

Large numbers of squirrelfish shelter within a wreck, the yellow background is almost entirely Tubastrea.

To Mauritius

The Echo Parakeet – one of several endemic birds that has been brought back from the brink of extinction by the Mauritius Wildlife Foundation

I’ve been keeping marine fish for a number of years now and I’ve been lucky enough to combine my hobby with a passion for scuba diving and seeing ‘real’ coral reefs. Not only does this hobby inspire my aquascaping attempts, but it has encouraged me to value wild reefs and to value them for their intrinsic value and ultimately the source of what has become a life-consuming passion.

Recently, I had the opportunity to travel to the small island of Mauritius. This tiny speck in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of Madagascar, is of course well known for its now extinct species – the Dodo being the one we all think of immediately – but it is also the subject of intense international efforts to save many more species that remain on the brink of extinction today.

I’d been lucky enough to visit some of the Island’s last remaining patches of natural forest amidst seas of sugar cane and I was lucky enough to photograph Pink Pigeons, Echo Parakeets and the Mauritian Kestrel, all birds that were until a few years ago represented by a handful of specimens.

These threatened birds illustrate the problems faced by island species across the globe: islands hold many species that have developed in splendid isolation and are highly unsuited to compete with aggressive colonisers introduced from other parts of the world, be they hungry sailors, mongoose or rats – the native endemic species suffer. Small islands, atolls and isolated reefs are underwater mirrors of the terrestrial world and as eager as I was to see rare birds of prey I was also very keen to explore the reefs of Mauritius to see what could be seen.

I have to admit, i’d not been aware of chrysogaster before this trip became a reality. It was my good friend Dale Pritchard of Ecoreef UK who suggested I should make them a priority and even asked me to squeeze a few into my hand luggage (sorry Dale, you were joking right?) – Photos would have to suffice! This wasn’t to be so easy though, but we’ll come back to that…

Like most tropical islands, Mauritius is surrounded by barrier reefs with associated lagoon systems, the barrier reefs can be as little as a few hundred metres off shore or a few kilometres depending on topography, though in general the eastern side of the island has more extensive lagoon systems. The lagoons are subject to a great deal of pressure from tourism associated development and are in many areas now devoid of the large expanses of hermatypic corals they once held. Water sports activities and the need to provide easy swimming opportunities for guests have in the past won out over conservation efforts. There are some hints that this might be changing though and the recent tsunami have reminded Mauritians that their reefs and mangrove swamps are of significant import in protecting them from the ravages of the oceans in a world where sea level rise is likely.

The mangrove systems and of course the sea grass and Caulerpa beds of Mauritius are fascinating and deserve an article in themselves – I was lucky enough to explore these whist snorkelling and at low tide and witnessed the extraordinary habitat they offer for young fish that will later be found on the reef – but for now it is further out and deeper that I turn my attentions.

My first dives were on the south coast of the Island, an area still considered ‘wild’ by many. I’d discussed my desire to see the local clownfish with my guide from the Cabana Water Sports Centre at the Telfair hotel and he promised to take me to Anemone Pass, which sounded just what I was looking for. The visibility was poor but as we descended into a wide crack in the reef, the numbers of anemone became apparent and I was looking at scores of square metres of rock carpeted with Heteractis magnifica specimens. At first I couldn’t see many hosting fish, there were good numbers of Dascyllus trimaculatus, but no clowns to be seen – darn this was going to be annoying so I switched on my camera and looked to the Dascyllus for a shot.

But no, there was no shutter noise, no flash firing and I looked in horror to see my camera housing was full of water and my Nikon was slowly turning to electronic soup. Needless to say I expressed my disappointment with some choice language but decided to complete the dive. Did I see any chrysogaster? no idea really.

My first ‘gaster, and no cameras were ruined! This image illustrates the reason for the genus name Amphiprion which derives from the Greek ‘amphi’ for both sides and ‘prios’ for saw. This refers to the serrated edges to the fishes’ opercula.

To cheer me up I visited Mauritius’ aquarium which featured the local undersea fauna – the stock is caught within metres of the bay under license from the authorities. Here I met Rasheed Ramjhun who guided me though the collection and here I met my first chrysogaster.

After several days of rinsing, stripping down and careful drying I decided to risk my housing again and managed to wedge my other Nikon (a D300s) into the housing originally made for a D200. It worked, to a certain extent, I could focus and fire the trigger and that was it, flash would be manual only. With some trepidation I took it snorkelling to ensure it was water tight before taking the plunge again.

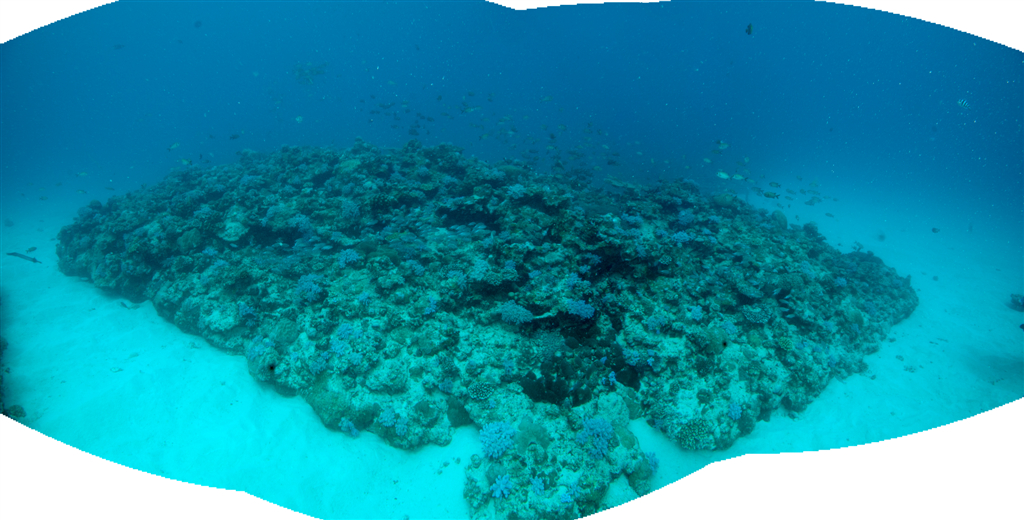

By this time we’d moved to the North West of the Island and I was diving with EasyDive at the Le Meridien Hotel. My guide Jonathan Cesar was also a photographer, so he was happy to guide me and then leave me to my own devices once we were on the dive site. Our first port of call was a small bommie system called Emily reef.

This wasn’t the highest tech aquarium you’d ever see, but Rasheed certainly cared for his charges and they were all in apparent good health.

“Why Emily?” I asked. Jonathan looked at me with a sad face and said, “Well, she was a diver and… here she drowned…” He kept this up for a few seconds before cracking up into laughter and said ‘no, it is named after a ship wreck”. This was going to be fun.

The visibility here was a little better and I managed to get several shots to piece together to show the reef in its entirety.

We toured the reef and bommie system for half an hour so before finding our target, a small outcrop that held three anemones and here the fun began. The first anemone we spotted was firmly ‘planted’ on the rock itself, complete with a resident pair of ‘gasters and I was able to get some acceptable shots.

However, as anyone who has photographed clownfish in the wild will know they are tough customers and will attack the dome ports of cameras. I looked over to see Jonathan gesticulating wildly at the larger of the two that refused to sit in its host and was more interested in trying to chase his camera away.

I spotted another anemone, another H. magnifica, that had taken up residence atop a former coral outgrowth, as I headed towards it to photograph its bright red column one of the two ‘gasters shot over to it and nestled into its tentacles and I also noted another to the right of me – two fish were hosting in three anemones. To add to their annoyance, every time they moved from one to another, they had to chase out a small shoal of Dascyllus trimaculatus.

All of this commotion didn’t go unnoticed and within a few minutes a Lionfish had swum over to see what all the fuss was about. Now in my experience lionfish always keep a respectful distance away, but not this one, he was within inches of my face and arm, so I bid a hasty retreat, right into the sand and well, the next photo shows what happened.

After what seemed like an age the vis cleared and I looked over to see Jonathan, I’m not sure how I could tell, but he was laughing at me. The Lionfish was still hungrily eyeing up the clownfish and I realised this had played itself out before. Every time the clowns move they were at risk form predation and every time the Dascyllus were ousted they too were at risk, my presence was just giving the lionfish the distraction he needed. Either way I managed to get some good shots.

Our next dive took us to a pair of barges that were sunk in the 1980s to become artificial reefs – the afore mentioned Emily and the Water Lilly. These ships were never going to be classed as the world’s greatest wreck dives but they were replete with fish including the only Anthias I saw on my entire trip and a beautiful pair of Moorish Idols.

The wrecks were surrounded by shoals of blue lined snapper and also had a few anemones with resident ‘gasters, including a specimen a few inches across within a tyre. I cursed my earlier camera disaster for ruining my macro lens, this would have make a superb shot.

Later that day we moved onto the wreck of the Stellar Maru, a larger ship sunk in the 1980s that landed on its side and was later ‘righted’ by a cyclone and now sits on its hull as intended, but it shows the power of the ocean and why most of the corals I’d seen were of the more massive and robust species and growth patterns outside the lagoon.

The Stellar Maru is a fishkeepers’ delight; various species of butterfly and angel are common place, with one large Emperor posing for photos. What I was hoping for though, was a chance to photograph Gem Tangs in the wild – another native of these parts, but this wasn’t to be and Jonathan said he very rarely saw them. Other Acanthurus and many Naso species were very common and were targeted by fishermen using large traps, baited with shoreline algae. I was told that commercial fishing was heavily regulated and licensed and the guides told me they thought the pollution from agriculture and industry was more responsible for the drop in fish stocks than overfishing.

So was it worth it? Undoubtedly yes, I am one camera and one lens down, but to see species that exist no where else is always an experience to cherish, both on land and underwater. Will I ever see ‘gasters available in my LFS? Not for a while I imagine, but if they were be added to a CB programme they would make a welcome addition to any stock list.

I was disappointed not to see gemmatus, but maybe I’ll have to return and I must say I’m very tempted to try to reach the Chagos archipelago to photograph Amphiprion chagosensis, but that may be a more difficult proposition.

A stunning example of A. chrysogaster in the ship wreck. Note the dark tail with white band and white band atop the trailing edge of the dorsal. The species is very similar to A. Allardi, though this has a white tail.

Jonathan photographs the ‘robust’ corals – currents can be strong and damaging especially during a cyclone.

0 Comments