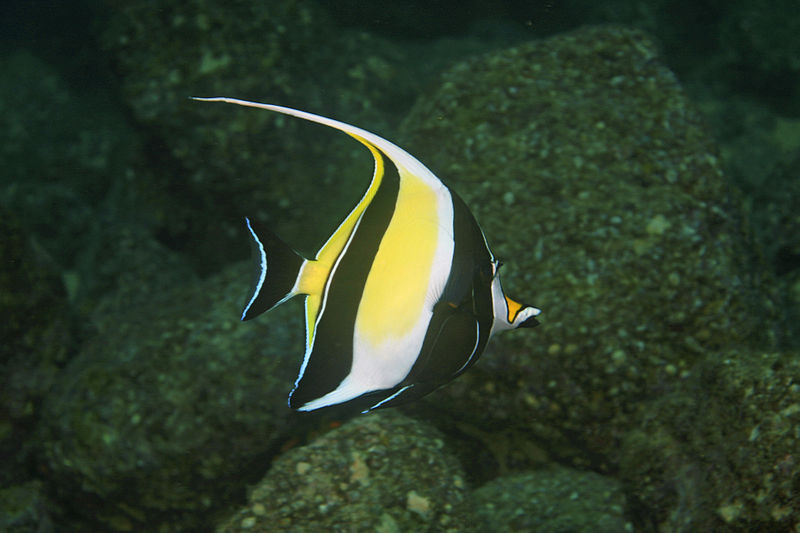

Few would argue that the Moorish idol is among the most handsome and graceful of fishes. Representations of this highly distinctive animal have served as marine iconography on everything from fine art pieces to shower curtains. It certainly has not escaped the interest (and nets) of the aquarium industry. For long it has been widely familiar even to novice aquarists. Nevertheless, it continues to have a limited presence in the trade on account of its poor record of survivability.

In all likelihood, no saltwater fish species has attracted, intrigued and frustrated aquarists like the Moorish idol. Its reputation as a delicate aquarium fish is indeed nearly as well known as its unique appearance. Somehow, this notoriety has actually elevated the regard many hobbyists have for the species; while most accordingly avoid it altogether, some find the challenge it presents to be downright irresistible. Thus, all too often, ill-informed and ill-prepared fishkeepers, armed with one trick or another, chose to learn the hard way that which so many before them have already discovered: Moorish idols are simply hard to keep. No reputable dealer (or responsible author) would assert otherwise. All of that being said, there is a considerable difference between hard to keep and impossible to keep. As a handful of capable aquarists have convincingly demonstrated, it is certainly possible to maintain Moorish idols in captivity for extended periods of time. Such cannot be accomplished with any particular trick, but rather through an uncompromising effort to:

- obtain healthy specimens.

- house them in an appropriate aquarium system.

- keep them with compatible tankmates.

- provide a varied, nutritious diet.

Of course, these objectives are important to successfully keep just about any aquatic animal; they are absolutely critical to successfully keep the Moorish idol. Especially concerning this species, meeting each objective will require (in the least) a practical knowledge of its natural history.

Classification / etymology

The Moorish idol (Zanclus cornutus Linnaeus, 1758) is the only extant member of the family Zanclidae (order Perciformes). Some authors place it in the family Acanthuridae (the surgeonfishes), though it differs from members of this group conspicuously in its lack of peduncular spines. It has also been placed (much more erroneously) in the family Chaetodontidae (the butterflyfishes). Fossil evidence of Eozanclus brevirhostris, an extinct relative of Z. cornutus that flourished during the Eocene epoch, serves to demonstrate a link between Z. cornutus and early acanthurids.

Long renowned for its beauty, the Moorish idol is a common subject of graphic art. Photo by JPPINTO.

In reference to distinguishable features of its body form, Zanclus comes from Greek za, an augmentative particle + agklino, meaning to “bow on the back,” especially like a scythe; Greek cornutus means “horned.” Hence, the derivative “horned scythe.”

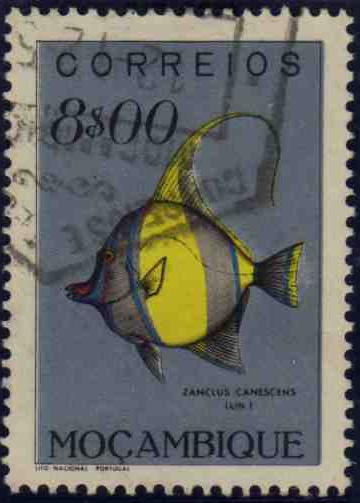

Linnaeus first described the species in the 10th edition of his work, ‘Systema Naturae’ (1758) using the names Chaetodon canescens and Chaetodon cornutus. Apparently, he assigned the additional name C. canescens believing that a postlarval specimen he was working with was a different species. Meaning “hoary or turning whitish,” the Latin canescens was used possibly to describe the fish’s washed-out nocturnal (or dead) coloration.

In an application of international zoological nomenclature rules (the rule of ‘first revision’), Cuvier, in Cuvier & Valenciennes (1831), described the genus as Zanclus and provided the type species name Z. cornutus. Günther (1876) established Z. cornutus as the valid name for the species. Nevertheless, the synonym Z. canescens is still used by some authors to this day; in some cases, both names are used in the same work.

The common name “Moorish idol” does much to convey the fish’s precious, mysterious, exotic nature. It is a reference to the Moors of North Africa, who are said to believe that the fish can bring happiness to those who dwell near it.

Distribution / ecology

It is becoming increasingly possible to keep the Moorish idol for extended periods of time in captivity. Photo by Georges Jansoone.

Z. cornutuscan be found (often in great abundance) across an extensive natural range. It is generally assumed that its wide distribution can be attributed at least in part to an unusually long, pelagic drifting phase during its larval development. It occurs throughout the Indo-Pacific and eastern Pacific oceans, with the notable exception of the Red Sea and Persian Gulf regions. It has been reported in the western Pacific from Kominato, Japan down to Lord Howe Island, and in the eastern Pacific from the southern Gulf of California down to Peru. Interestingly, it was reported near Pompano Beach, Florida in 2001–quite plausibly a consequence of aquarium specimen introductions.

Z. cornutusis rather adaptable, inhabiting a variety of hard-bottomed habitats from seaward reefs to murky harbors. It occupies a depth range of 3-182 m. It is a roving grazer that is frequently found in pairs. However, sizeable shoals can amass in areas that support an abundance of sponge, tunicates and other benthic invertebrates upon which it feeds. The author has observed the species in presumably brackish water near a large drainpipe, foraging amidst trash in surprisingly close proximity to feral tilapia.

The extinct Eozanclus brevirhostris appears to be a link between the Moorish idol and its acanthurid cousins. Illustration by Apokryltaros.

It has been speculated that Zanclistius elevatus shares common ancestry with the Moorish idol. Photo by Ian Skipworth.

Morphology

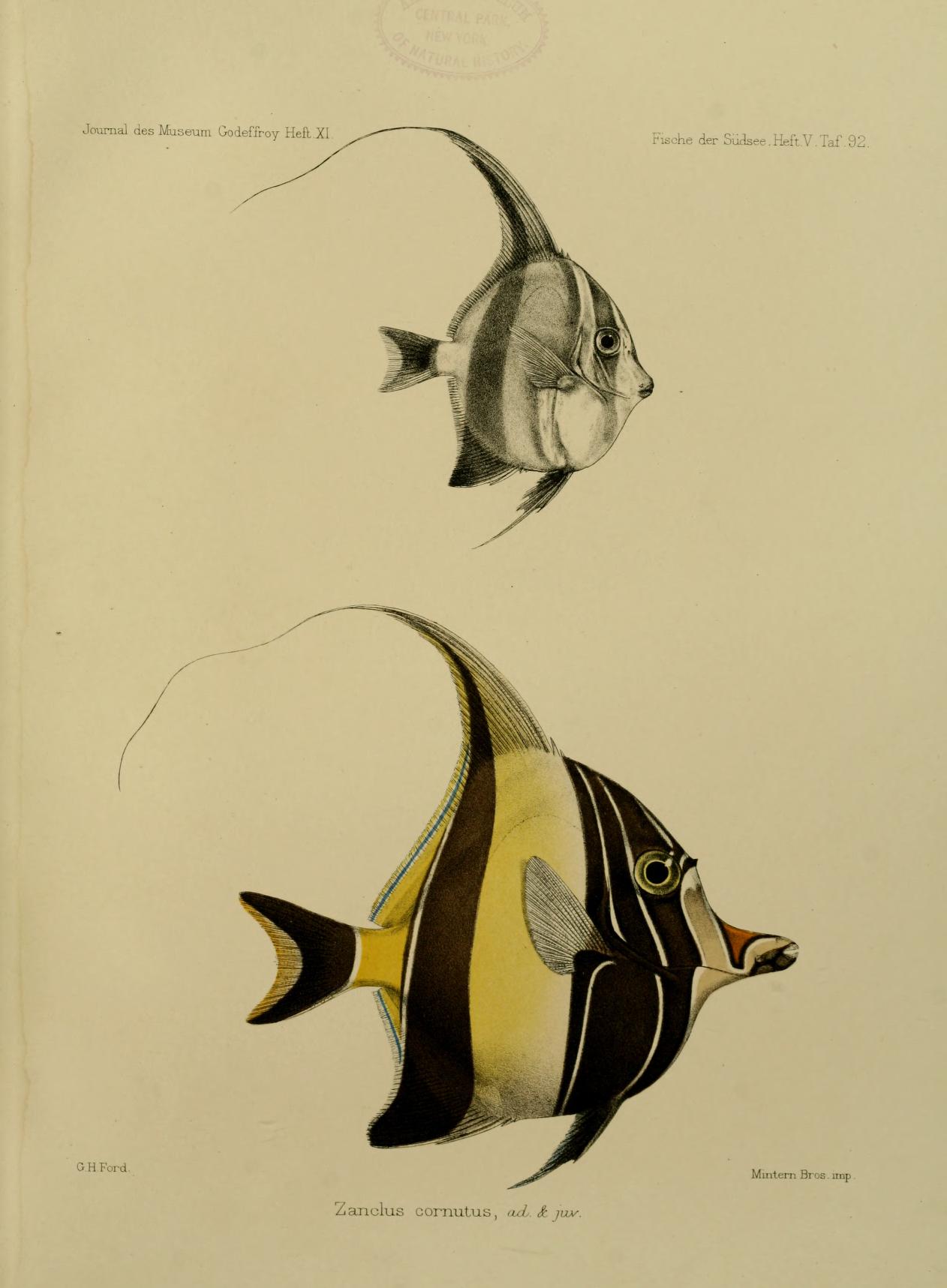

The late postlarval form is relatively large at 8 cm total length. Before transforming into the adult form, it sheds the preorbital spine on each side of its head. Illustration by G.H. Ford.

Z. cornutusis characterized by a strongly compressed, highly elevated, discoid body. It reaches a maximum body length of 22 cm. It has a slender, protruding, tubular snout and a diminutive mouth lined with long, bristle-like teeth. Thickened bones in its forehead develop with age into a prominent horn-like structure that projects from just above the eyes. The preopercle and caudal peduncle are unarmed. It has 6-7 dorsal spines, 39-43 dorsal soft rays, 3 anal spines and 31-37 anal soft rays. The elongated dorsal spines form a highly distinctive filament.

Its base color is white. The tip of the upper jaw is black. Most of the lower jaw is black. A bright orange patch that is outlined in black covers the top of the snout. A wide, vertical black band runs from the first dorsal spine to the ventrals. Two thin, curvilinear bluish lines run over the first black band from the origin of the ventrals to the front of the dorsal fin and from the abdomen to the origin of the dorsal fin. A third, but less distinct, bluish line runs up and back from the eye. A second vertical black band runs from the dorsal to ventral rays, widening ventrally. A thin, vertical white line runs along the posterior of the second black band. A bright yellow-orange patch extends from the caudle region where it is bordered by a thin white band, to the mid-body where it fades into the white base color. The caudal fin is black, and is edged in white.

The distinctive elongated section of its dorsal fin is often referred to as the philomantis extension. Illustration by Francis Day.

Heniochus diphreutes is so similar in appearance to Zanclus cornutus that it is often called the false Moorish idol. Photo by Bryan Harry.

Husbandry

Zanclus cornutus occupies a variety of habitats; this individual was found on a rocky reef near Panama. Photo by Laszlo Ilyes.

The Moorish idol has proven itself to be quite delicate in the aquarium environment. This is particularly so during the period of adjustment that follows capture, transport and holding (which often precedes yet more transport and holding). Regarding this species, with few exceptions, a compromised specimen is as good as dead.

Sadly, a rather large number of recently imported individuals are seriously compromised due to shipping stress. Consequently, it is incumbent upon hobbyists (at least those that hope for the slightest chance of success with this fish) to acquire specimens from the best available sources. While careful handling must be employed throughout the entire supply line, it seems to be especially important that specimens are shipped individually in oversized bags. Specimens harvested from the eastern Pacific are said to adapt more easily to captivity (perhaps only because of the shorter shipping route). Generally, younger individuals are somewhat more tolerant of shipping stress. Further, younger individuals generally are more tolerant of acclimation stress and are better suited to captivity.

Perhaps owing to shorter shipping routs, specimens collected from Mexico and Hawaii are reported to have a better survivability. Photo by Dominik Keller.

Specimens should be held by the dealer and personally observed by the buyer for weeks before purchase. This is not a species that should be purchased online (even some online venders that offer them unequivocally say so). Because of the risk (if not high level of care) involved in holding this fish, some retailers might avoid quarantining specimens prior to sale; in this case, one does best to avoid them. It is advisable to obtain specimens from dealers who will not only quarantine for 2 weeks or more, but will also be willing to demonstrate that the animal is feeding well.

Transport time from the dealer to the home aquarium should be as short as possible. All tank lights should be shut off for the remainder of the day. Whatever acclimation method is used, it should be smooth and gentle. Then, the animal should be left alone; while new acquisitions should be monitored periodically, one shouldn’t cause them any undo stress by skulking at the front of the tank all evening.

Pairing captive specimens is potentially a worthwhile, though very risky, practice. Photo by Brocken Inaglory.

The typical reef aquarium set-up should be adequate to house Z. cornutus provided that it is very large (i.e., 200 gallons or more) and completely mature, and that excellent water quality is maintained. An abundance of rockwork (albeit with long, unobstructed swim paths) will be appreciated.

Healthy live rock will often abound with organisms that can provide a source of nourishment for the new fish. If conventional prepared foods are refused, clam or mussel on the half shell may be accepted (remove uneaten portions nightly). In the proper environment, Z. cornutus can be trained to eat flake foods from its keeper’s hand in as little as a couple of weeks. While it is indeed often challenging to get newly imported Z. cornutus to begin feeding, it should here be emphasized that the long-term health of this animal depends greatly upon having a properly balanced diet. Z. cornutus is not herbivorous as many once believed (perchance because of its resemblance to acanthurids); while it may be worthwhile to regularly offer it certain plant-based foods (e.g., nori), a highly varied fare that includes sponge (often found in frozen marine angelfish foods) is more appropriate for this omnivore.

Tankmates for the Moorish idol must be selected judiciously. As fragile as it might seem to be, this fish can be a real menace to any others that dare to get in its way. It can be especially aggressive toward its own kind; while there may be real benefits to keeping this fish in pairs, the likelihood of conspecific aggression is far too great to suggest housing more than one individual per tank. All the same, it can be a target for pugnacious tankmates. Fin nippers (e.g., some damsels and wrasses) may find its filamentous dorsal fin impossible to ignore. Bullies and tyrants (e.g., triggerfish) may be endlessly at odds with it on account of its apparent lack of submissiveness. Highly territorial fish (e.g., tomato clownfish) may constantly batter it as it repeatedly wanders–grazing–across their turf. Any tankmate that exhibits even the slightest threat to a Moorish idol should be removed promptly.

Younger individuals tend to adapt more easily to captivity. Photo by Chris Turnier.

Conclusion

Many aquarium hobby authors have written about this animal in the past. Most tend to strongly dissuade aquarists from attempting to keep the species. The typical argument for this position evidently is an ethical one, drawing attention to the fact (and it is a fact) that (at present) few Moorish idols collected for the aquarium industry survive the first few weeks of captivity. In point of fact, this fish is quite abundant in the wild and has an unusually wide distribution. If one were to make an argument from the position of a conservationist, it certainly could be said that the impact of collecting this fish is far lesser than many other commonly kept–but naturally uncommon–fishes, regardless of captive survivability.

Few would deny that the Moorish idol is an amazing animal. Nevertheless, owing to repeated failures reported by others in the hobby, most aquarists elect not to acquire them. Considering the relatively great number of resources that are required to successfully keep them, this is quite understandable. Such is a case wherein an entire aquarium system must be built around a sole occupant. One makes no overstatement in saying that this is a species for the advanced aquarist. Still, in consideration of all of the technological and methodological refinements taking place in the hobby, there is every reason to conclude that the Moorish idol will yet become a staple of the ornamental fish trade. This will only be accomplished when distributors and retailers–and then, by extension, hobbyists–recognize that success with this species cannot be had on the cheap. They will find that obtaining strong, young specimens, housing them in a habitable living space, providing them with an appropriate diet and keeping them with suitable tankmates actually works. Moreover, they very likely will find that the considerable effort and investment is entirely worth it.

Those who are not equipped to provide the highest level of care for this species do best simply to observe it in its natural environment. Photo by Brocken Inaglory.

0 Comments